Toxic brew heightens child labour risks in African tea, coffee, cocoa

Human Rights Outlook 2020

by Ryan Aherin and Eric Humphery-Smith and Alexandre Raymakers,

The negative economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, combined with fluctuating demand and falling prices for key export commodities, will make it more difficult to eliminate child and forced labour in African commodity supply chains over the next couple of years.

Using our Commodity Risk Dataset, we identified tea, coffee and cocoa as some of the key commodities from the continent where child and forced labour may worsen as a result of economic circumstances and drive up the risk of violations appearing in corporate supply chains.

Register now for our webinar where we discuss this Insight in further depth

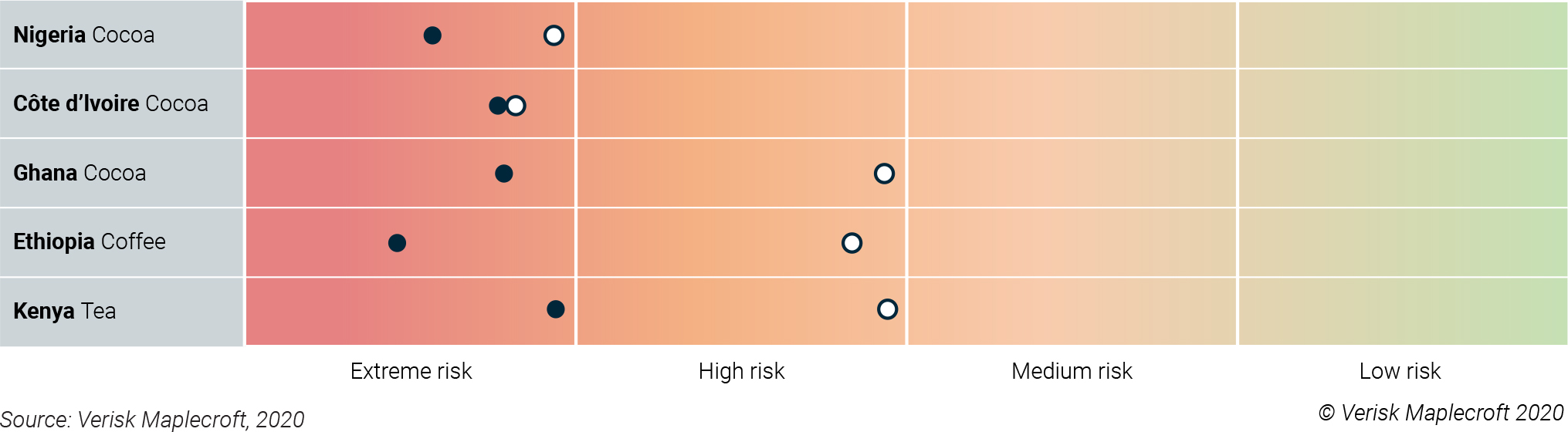

Figure 1 shows that these commodities are already at a ‘high’ or ‘extreme risk’ of child or forced labour in key African producing jurisdictions. Direct evidence of child labour has been identified in relation to the production of the commodities in each of these countries in the past five years, and the economic outlook suggests that the scores for each could worsen.

Market prices don’t reflect realities on the ground for growers

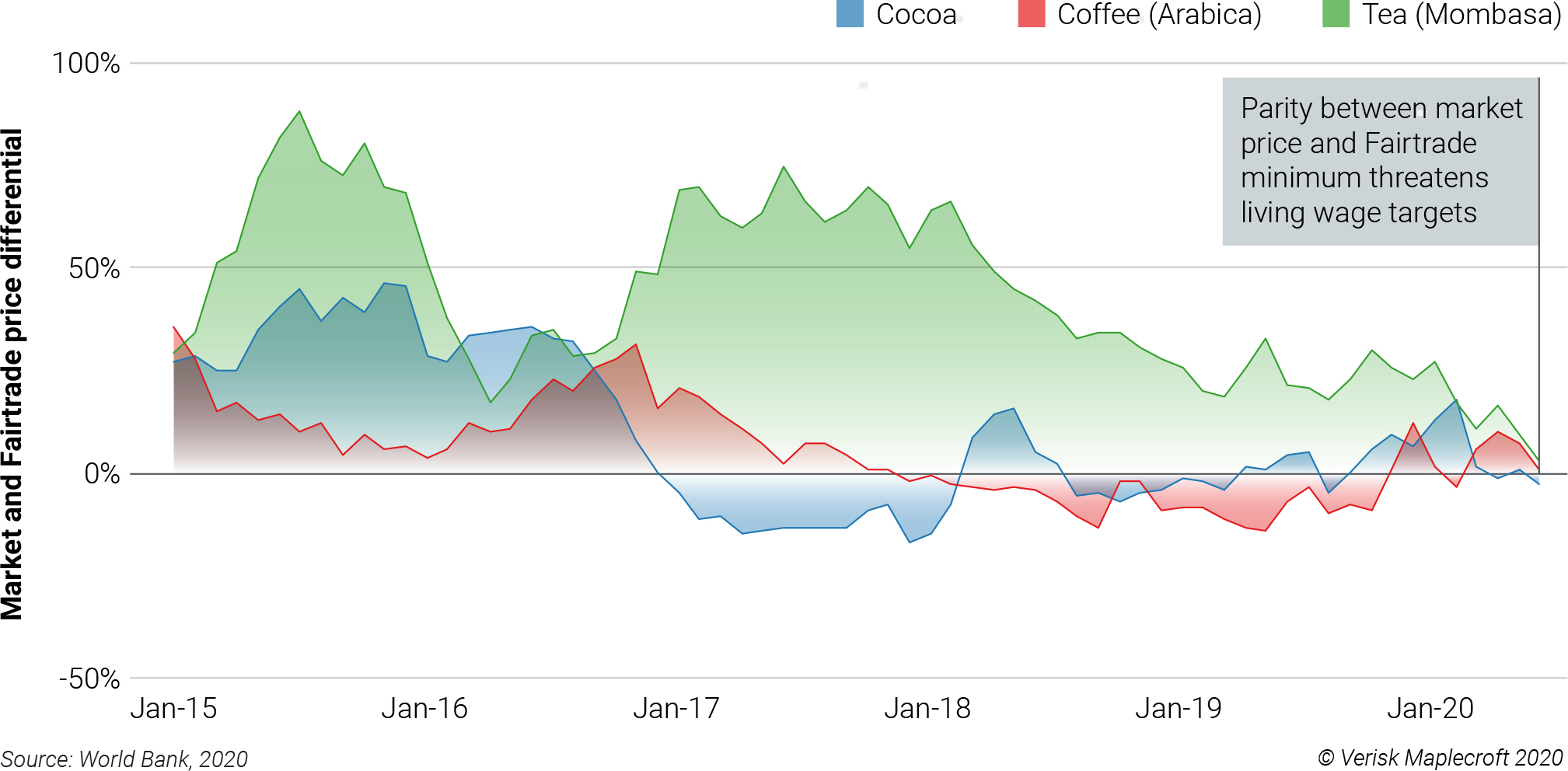

The disparities between market and target living income prices are likely to continue undermining attempts to eradicate child labour in supply chains. Market prices have consistently fallen below Fairtrade minimum prices for coffee and cocoa in the past three years. While tea has traditionally fared better, with Kenyan tea typically trading slightly higher than the global competition, prices have dramatically fallen in the last three years relative to the Fairtrade recommended price. These low prices put greater pressure on growers to lower production costs as profits fall. Therefore, the economic strain of the COVID-19 pandemic will lead to a short-term increase in child labour risks that will create longer term setbacks for efforts to eliminate the practice.

Declining cocoa prices over the past two decades have meant that farmers in Côte d’Ivoire increasingly seek to compensate for their reduced income by expanding their growing areas. This has resulted in children being trafficked in from neighbouring Burkina Faso and Mali to help clear forest. While border closures associated with the pandemic have decreased the flow of child workers between countries, this has compelled many farmers to resort to relying on underage relatives to meet labour requirements.

Ethiopian coffee growers have also been struggling to make ends meet, with farmgate prices bottoming out at USD 0.26/kg in 2019. As school is not compulsory and often unavailable to most families living in poverty, many children begin working alongside their parents to support family income. Investment in childcare and rural access to education could help alleviate the situation, but reduced government revenue from exports and COVID-19 containment measures means this option is currently not on the table.

While Kenyan tea prices have generally traded well over the Fairtrade minimum for several years, the price at the Mombasa auction, which accounts for 95% of the country’s tea supply to the export market, remains at a three-year low amid depressed global demand due to the pandemic. Even though child labour has been linked to production, violations related to tea production have historically been less extreme than those observed in cocoa and coffee supply chains. However, the economic implications of the pandemic over the next couple of years are likely to create an environment where child labour violations will increase if growers do not receive adequate financial protections.

Failure to tackle forced child labour could lead to serious penalties

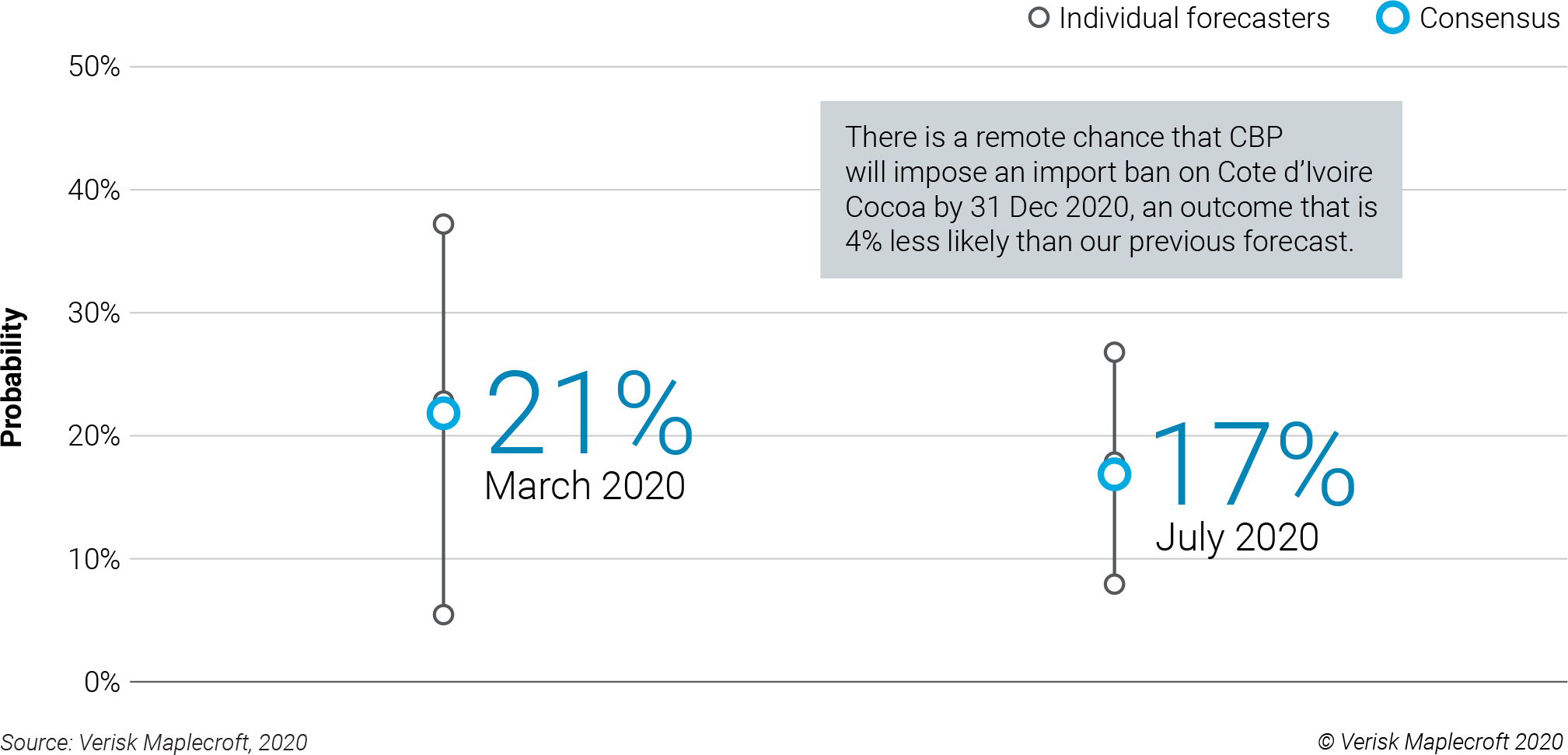

Due to the severity of abuses in Côte d’Ivoire, there is a heightened risk that punitive action will be taken by EU and American authorities. For example, the US Customs and Border Protection Agency (CBP) is currently investigating links between cocoa production in Côte d’Ivoire and forced child labour. The agency has the legal authority to withhold imports of goods associated with forced labour. As a worst-case example of the forms of punitive action, the CBP has recently issued a wholesale ban on tobacco from Malawi due to associations with forced child labour. However, the agency’s actions tread a fine line between compelling suppliers to eradicate forced child labour and causing harm to vulnerable smallholding producers.

Our team of forecasters see a 16.7% chance that the CBP will issue a total ban on cocoa from Côte d’Ivoire over the issue of forced child labour. The underlying reason for this remote chance is that such a ban would result in a direct economic hit on the US’ largest chocolate manufacturers, given Ivorian cocoa’s leading role in market supply.

Download the full report

Human Rights Outlook 2020Rather, we think it is likely that the agency will take a small-scale, targeted approach to combat forced child labour associated with Ivorian cocoa imports. Still, such a targeted measure will be difficult to implement given the challenge of traceability of cocoa in Côte d’Ivoire, which is often aggregated at the co-operative or regional level rather than by individual producers.

Similarly, it is likely that Western governments will take more punitive action to combat child labour in tea and coffee supply chains as the 2025 SDG deadline to eliminate child labour approaches. There is growing support in the EU for stricter reporting and supply chain tracing. Failure by industry stakeholders to take preventive action now will likely result in painful consequences later on.

As the main driver of child labour in commodity supply chains is poverty resulting from low and unstable prices, importers have the greatest opportunity to affect positive change. Buyers can work more closely with local governments to ensure that higher market prices are reflected in farmgate prices and producers have a safety net if market prices drop. Furthermore, ensuring that commodities are purchased at prices that reflect the true cost of production, improving livelihoods over the longer term, will therefore be the most effective solution to child labour risks.