Food insecurity in Central America, Caribbean bigger threat than COVID-19

by Jimena Blanco and Victoria Gama and Mariano Machado,

As the pandemic takes its toll on Latin America, food import-dependent countries are likely to see a different crisis unfold in the coming weeks and months. Sickness, transport interruptions and delays, and quarantine measures limiting workers’ movement are all combining to disrupt food supplies, forcing prices upwards and intensifying the risk of unrest.

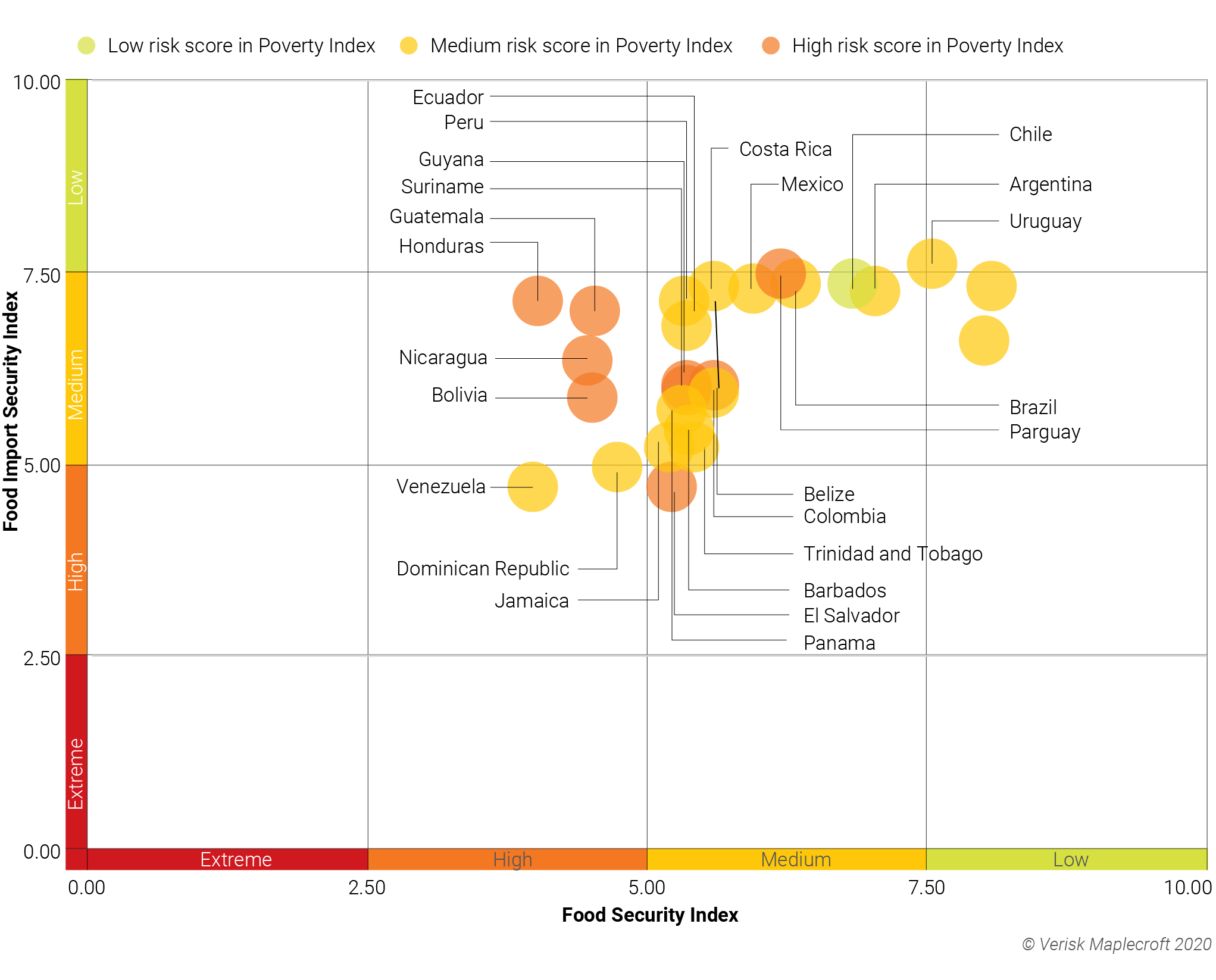

Securing access to staple foods is an urgent challenge, and failure to do so will have a wider impact on the region than COVID-19 itself. The pandemic is exposing critical chokepoints that threaten vulnerable populations’ access to essential commodities. Our Food Import Security and Food Security indices show that the majority of Central America and the Caribbean (CAC) countries are already rated as high risk to food insecurity, both in terms of import vulnerabilities and local production capacity.

The uncertain duration of the pandemic, alongside restrictions on movement, and the lack of a safety net in these countries is going to generate discontent that electorates will not be able to channel through the ballot box due to the suspension of political rights through states of exception. Rising food insecurity will intensify this discontent, stoke unrest and erode public support for governments in an important election year. More than two-thirds of the countries in the higher risk group had significant elections planned in 2020, with most now rescheduled.

Fiscal constraints threaten a humanitarian crisis

Governments in CAC will face severe challenges to address food availability – ranging from budgetary constraints to disruption in sourcing countries. Despite setting retail price caps and export bans, countries with higher levels of food import dependency will suffer a major economic contraction. No country in CAC will post a positive economic performance in 2020.

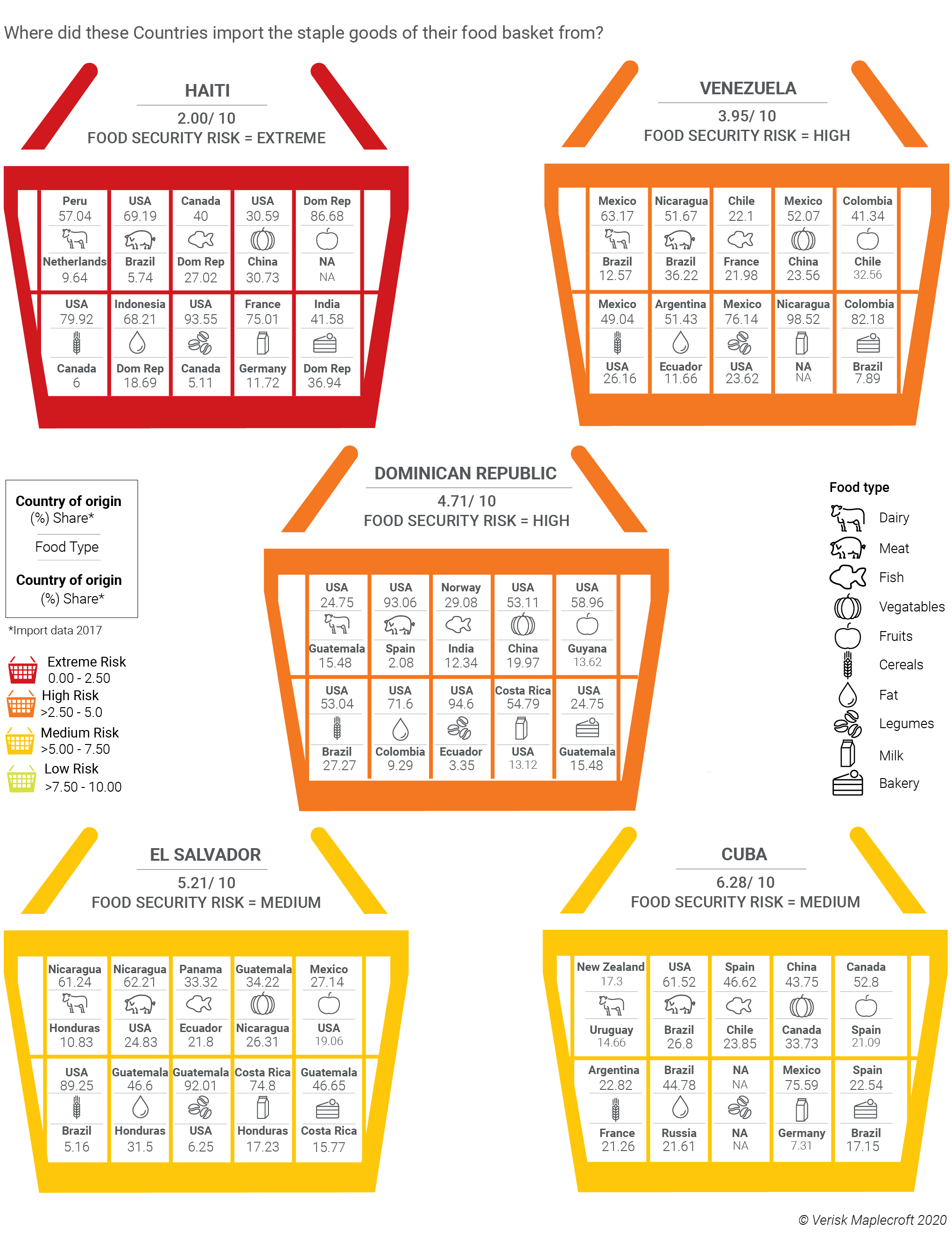

The region’s top trading partners for agricultural products – the US, Brazil and Mexico – are facing a major human toll from the pandemic and sustained closedown measures, which will create delays for buying countries. Should shortages in grocery stores in key exporting countries result in export bans, CAC would face a severe shortfall of staples, such as rice, meat and dairy, regardless of their ability to pay.

Ultimately, the health crisis could become a secondary concern if food shortages compound an already difficult situation and push up social upheaval. Haiti is the most at risk country. According to the UN, nearly 4 million people there already face severe hunger, which is illustrated by the country’s extreme risk rating in our Food Security Index. Haiti relies heavily on food imports such as rice, 88% of which comes from the US. Peru and the Dominican Republic – which remain under lockdown - are also key sources of basic food basket items (see figure below).

In South America, Caribbean facing Venezuela, with over 9 million people at risk of food insecurity, is another one to watch.

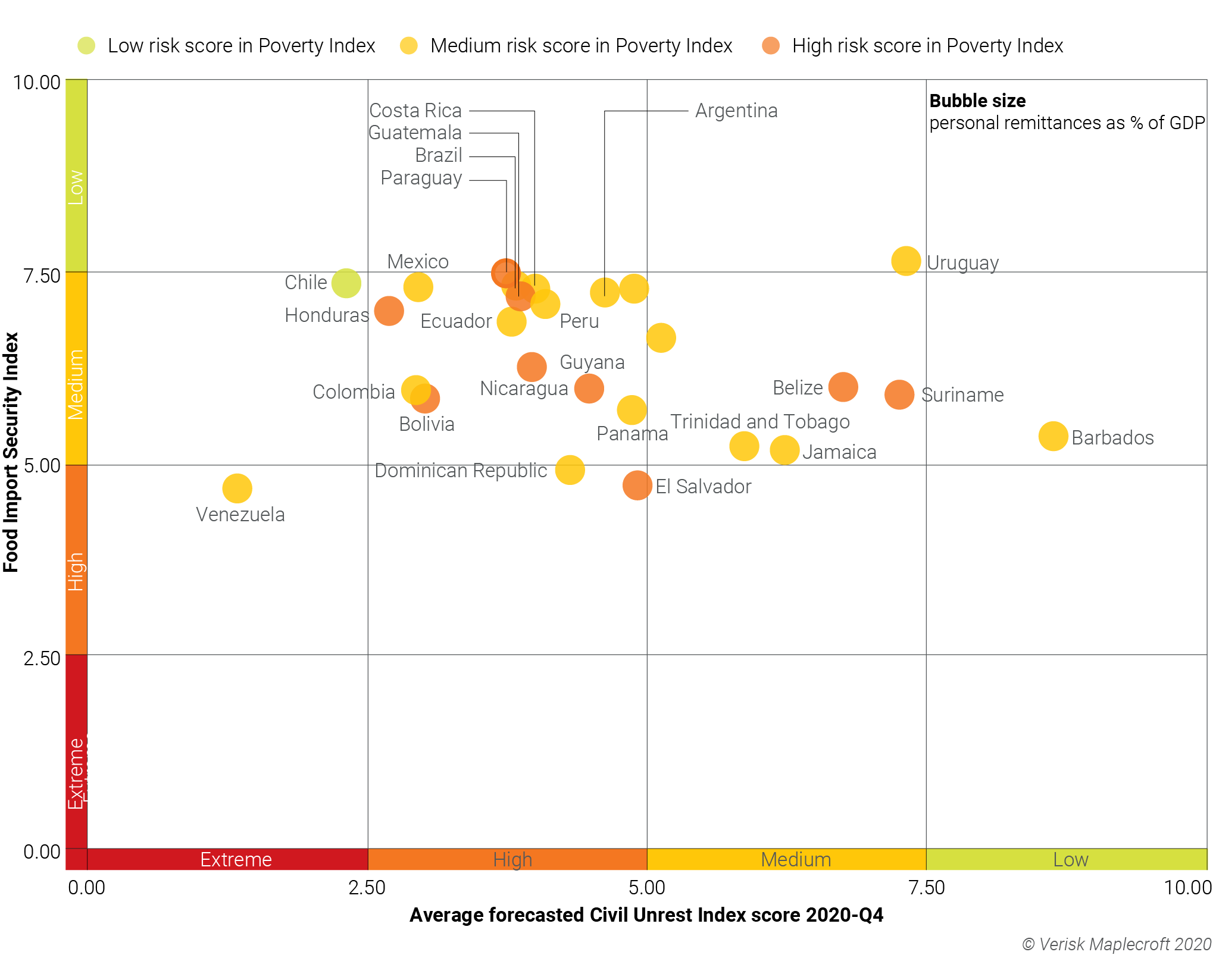

Food price increases combined with the presence of a large informal workforce and widespread poverty will push up the risk of looting and civil unrest across CAC – even while lockdown orders are in place. Latin America and the Caribbean has 130 million informal workers, who are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 containment measures – no work means no food. In El Salvador, Trinidad and Tobago, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and the Bahamas, informal sectors range from 62.9% to 30% of the workforce.

Despite government measures, we expect rates of informal working to grow as the impacts of the pandemic on business hit home. This group spends over 25% of its income to food and will be at higher risk if prices rise or shortages become more frequent.

Hanging by a thread

Our Civil Unrest Index Projections (2020-Q4) forecasts a high risk of disruption in most CAC countries. Vulnerable communities are exposed to high levels of violence in CAC, increasing the propensity for rioting. And illegal armed actors could use the opportunity to flex their muscles and exert authority further.

Gangs are openly challenging the state’s role in some countries. MS-13 and 18-S in El Salvador are enforcing the lockdown and delivering food to vulnerable communities. Once lockdowns are lifted, the state may be unable to reassert its role, or its presence may be deemed irrelevant by local communities, with gangs legitimising a political role.

With most congresses working remotely – or with limited sessions – and judicial powers across the region focused on the most urgent matters, checks and balances are currently crippled across the region. Controversial decisions threatening fundamental civil and political rights, including freedom of expression, the right to privacy, and freedom of movement, can go unchecked, building up additional discontent. The longer institutional paralysis continues, the higher the risk of the social time bomb exploding.

We anticipate economic stress to worsen employment and poverty indicators, pushing up civil unrest risks and undermining political stability. If governments resort to prolonging lockdowns to contain unrest, they will further strain food security and add another source of pressure to civil unrest risks. Therefore, our Political Stability Projections for the final quarter of 2020 paint a bleak picture for key CAC economies, as the health crisis and its economic fallout risk triggering a humanitarian crisis, with informal workers relying on governments that could be unable to meet the food requirements of vulnerable populations.