Electric Vehicles drive nickel back into spotlight

Nickel is a key component of the batteries being developed for use in electric vehicles (EVs), with most blends expecting to use 20-30% Ni, with some prototypes in testing even using a blend that is closer to 50% Ni. With many governments actively promoting a transition to EVs from combustion cars, the global scramble for battery-related commodities such as nickel, cobalt and lithium will only intensify over the coming years. Furthermore, efforts to switch to renewable energy for national power grids will most likely require the use of high-capacity batteries for backup power, which also have a high nickel blend. As these policies solidify, nickel will become a crucial material defining energy security towards the latter half of the 21st century.

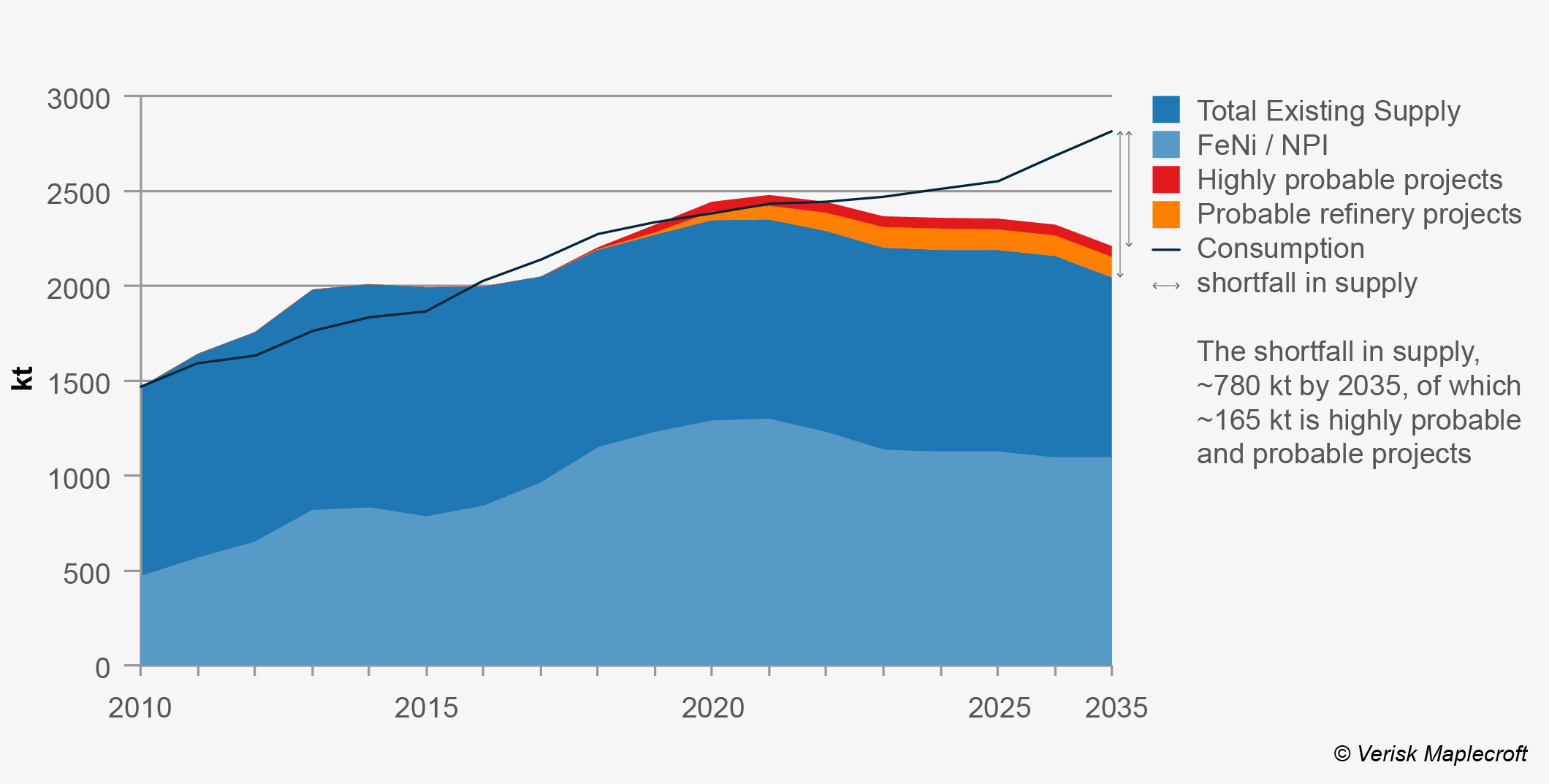

As the majority of nickel production consists of lower grade FeNi and nickel pig iron (NPI), less than half of the nickel being produced today is of a high enough grade to be used for EVs. According to Wood Mackenzie, demand for nickel is expected to outpace production by 2022 (see Chart: Projected nickel supply and demand). Even when accounting for projects currently under consideration, there will be a significant gap between supply and demand.

The industry is considering alternatives to primary sources of nickel to alleviate the anticipated crunch on supply. These sources could include recycling and the mixture of nickel intermediates with sulphuric acid, but even these projects will only provide some modest relief to supply constraints. As such, non-EV manufacturers that rely on nickel alloys will be more vulnerable to supply shocks and rising prices.

China well placed to take advantage of the nickel sector

China’s dominant influence over the nickel market will benefit Beijing’s broader strategy to secure access to the raw materials needed to rapidly develop its domestic EV sector. Nickel production and demand has been primarily driven by China in recent years. Rapid expansion of Chinese construction activity in the mid-2000s and 2010s drove global demand for steel, while Beijing’s recent clamp down on expansion has led to a surplus while the flooding of the market with lower grade nickel pig iron (NPI) has depressed nickel prices. This has made investment in the production of higher grade nickel unprofitable.

China’s massive consumer automobile market, which makes up nearly 30% of global automobile sales, gives it a considerable edge towards dominating the EV sector. Similar to how it created an incubator for its solar power sector, Beijing is using subsidies to promote the sales of domestically produced EVs. The strategy is already paying off, nearly half of all EV sales in 2017 occurred in China of which 94% were domestic brands.

While foreign automakers will want to tap into the massive Chinese EV market, even if they are only vying for scraps, they are required to partner with a domestic brand. This will give Chinese companies an extra boost through technology transfers. These factors will give China substantial advantages over both the development of new EV technology and the supply of key raw materials required for producing EVs.

Volatile policy environment threatens to disrupt nickel supply

Disruptive policies implemented by major nickel producing countries such as Indonesia and the Philippines has contributed to the volatility of the sector. In 2014, Indonesia imposed a ban on raw mineral exports of nickel, which disrupted global supplies and caused an increase in prices. The intent of the ban was to force nickel producers to invest in the domestic smelting infrastructure.

The ban was initially successful since the shortage of supply, which was caused by the ban, increased nickel prices to the extent that costly investment in smelting was more profitable. However, in 2017 the government eased restrictions to allow producers to apply for permits to export low-grade nickel ores. This led to an increase of NPI production, which caused prices to drop and capital investments in several smelter projects were abandoned or put on hold.

Likewise, in 2017 the government of the Philippines issued suspension and closure orders to most nickel mines amid an environmental crackdown on the sector. Further uncertainty looms over the future output of Philippine nickel production as the government considers overhauling mining laws, tax and revenue sharing structures and considers its own ban on raw mineral exports. While the Philippines are not a major producer of higher-grade nickel, disruptions of low-grade supply can cause volatility in the price of higher grades.

Climate change threatens productivity and resilience

A significant portion of future battery-grade nickel production will likely take place in regions adjacent to the Indian Ocean. Climate change estimates suggest that rising temperatures in the Indian Ocean will lead to significant increases in the frequency and intensity of tropical cyclones by 2070.

In January 2018, a tropical cyclone disrupted production at the Ambatovy mine in Madagascar. The storm damaged smelting facilities and will have a negative impact on the site’s production through the second quarter of 2018. Increased cyclone activity will also threaten to disrupt operations and shipping facilities in Western Australia, which is set to be a major producer of battery grade nickel.

The negative impact of climate change on labour productivity in South East Asia also threatens nickel mining operations in the region. Rising temperatures increase the likelihood of workers experiencing exhaustion which can negatively impact health and lead to workplace accidents. Our climate change projections estimate that the region will experience a 16% decrease in labour productivity due to heat stress, with major nickel producing countries Indonesia and the Philippines experiencing losses of 21% and 16% respectively.

The next five to ten years will be a crucial period for the development of the global EV supply chain and the wider renewables market. The procurement of key raw materials for batteries and other renewable technology will determine both the commercial success of manufacturers and the ability of governments to implement policies to meet climate targets and benefit from the growing green economy. As demand for nickel outpaces supply, higher prices will likely be passed on to consumers, which may delay more widespread adoption of EV technology by consumers or pressure governments to subsidise these costs so they can meet targets to cut back on carbon emissions.