EU's carbon border tax still a long way off

by Franca Wolf,

The EU Commission announced its new flagship policy, the European Green Deal, on 11 December. The deal includes plans for a carbon border tax that would require non-EU companies exporting into the EU to pay additional import tariffs based on the carbon content of their goods.

The policy has the support of wide swathes of EU industry, including steel and aluminium producers, which want to ensure non-EU producers do not benefit from lax emission standards in their country of origin and therefore gain a competitive advantage.

A number of obstacles make it unlikely that the EU Commission will get member states’ approval immediately. Even so, in this clash between trade and climate, we are likely to see the EU increasingly use its economic power to advance its climate policy goals. The long-term direction, therefore, points to the eventual introduction of a carbon border tax, which would raise the monetary and regulatory burden of exporting into the union.

A blessing for EU producers is a burden for producers outside the EU

The Commission, led by Ursula von der Leyen, is seeking a carbon border tax to advance climate protection both in and beyond the EU. The tax would also tackle the concerns of EU producers, whose obligation to observe EU carbon policies puts them at a competitive disadvantage to foreign companies operating under less stringent emissions standards.

The EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) requires energy-intensive industries within the EU to purchase allowances for their carbon emissions. From 2021, the number of allowances available will be reduced, and this drives our assessment of a gradually higher carbon price over the next decade. The carbon price has already increased more than threefold since 2018 to around EUR25 per tonne. By requiring non-EU producers to pay a comparable import tariff on the carbon content of their products at EU borders, EU and non-EU producers would incur similar costs for their carbon emissions.

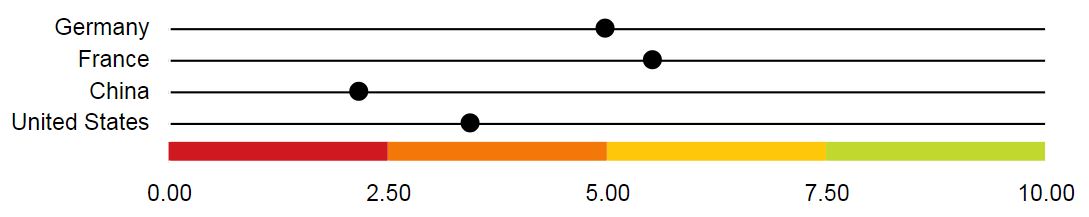

For non-EU producers, the border tax would raise the monetary and regulatory burden of exporting into the union. Our Low Carbon Economy Index evaluates countries' progress towards, and commitments to, improving the energy efficiency of the economy as measured by CO2 emissions. The closer to 10 a country’s score is, the further it has progressed towards a low carbon economy. As shown in the figure below, Germany and France, the EU’s largest economies, have lower risk scores than their two largest trading partners, China and the United States.

The fact that the US and China have more carbon-intensive economies than the EU means that making them pay the proposed carbon border tax would likely raise the price of their goods in the EU market.

China has already criticised the carbon border tax plans as a protectionist measure that would undermine global climate action. We expect the United States to also condemn it, along with most of the EU's other trading partners. The carbon border tax thus risks becoming another hot spot in global trade disputes.

Obstacles abound

Although there is scope to design elements of the carbon border tax to improve its feasibility, and make it compatible with WTO rules, several obstacles stand in its way. For example, Finland and the powerful Federation of German Industries (BDI) have already criticised the tax over concerns that it would stoke trade tensions. Other countries will likely join their opposition.

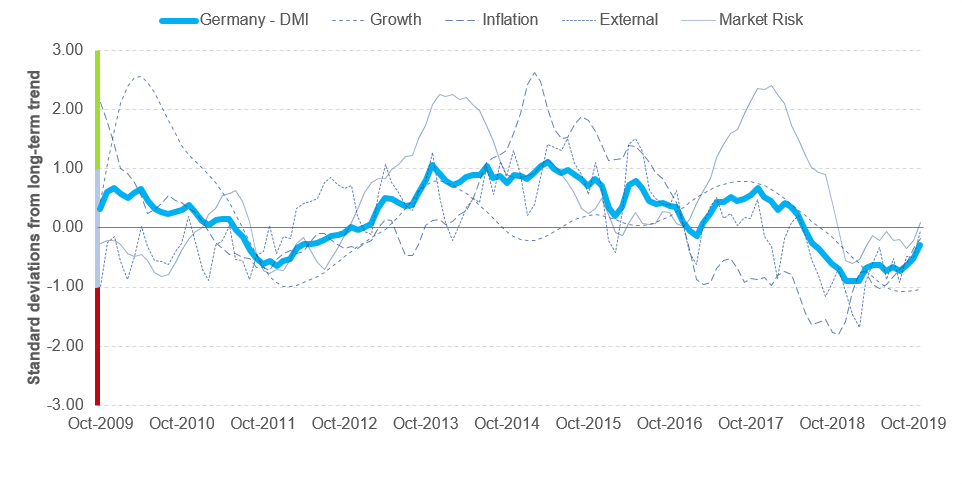

And while the fossil fuel-intensive eastern EU countries tend to challenge EU climate legislation, export-reliant, major EU economies will be even more likely to oppose the proposed tax. Even if the tax were to be made WTO-compliant, these countries are concerned about fuelling protectionist policies and thereby weakening EU economies, which are already slowing due to global trade disputes. Our Dynamic Macroeconomic Index below shows that Germany has already registered an economic downturn in the external pillar due to trade uncertainty.

Therefore, we believe that economic concerns will trump environmental considerations at this point, and that the EU Commission is unlikely to win the required unanimous support of all member states for the carbon border tax as things stand. This means that the EU is unlikely to adopt a carbon border tax in 2020.

Longer-term prospects for carbon border tax more favourable

The probability of the EU introducing such a measure rises in the future. The likelihood of adoption will increase as the European economy picks up pace. More importantly, rising pressure to reach the EU’s emissions reduction targets and growing competition from cheaper, more polluting products manufactured outside the EU are likely to progressively increase member states’ willingness to adopt a carbon border tax.

The EU has already linked climate protection and trade in recent years, for example by making future trade deals dependent on trade partners’ membership in the Paris Agreement. However, the decision in April 2019 to open negotiations with the US on a limited trade agreement has shown that the commitment to climate protection is mostly political, and economic interests take priority. Even so, the new EU Commission has vowed to use its regulatory clout in a global context, and we expect Brussels to try to increasingly instrumentalise its economic power for climate goals.

This drives our assessment that we are likely to see the EU adopt a carbon border tax in the longer term. While it is difficult to predict when a critical supporting mass will be reached, the dynamic points to more ambitious climate action in the 2020s, and this will likely include a carbon border tax sometime after 2025.

Find out more about Climate change and environment