Electric vehicles: ESG risks set to rise as demand for raw materials ramps up

by Meagan Norris and Tatiana Tsaprailis and Stefan Sabo-Walsh,

The vision of clean, green and energy-lean electric vehicles is now firmly recognised as representing the future for the automotive industry. The well-polished image of the final product may, however, live in stark contrast to the realities of what will happen in electric vehicle (EV) supply chains. As market share and sales grow over the next 15 years, so will the appetite for the raw materials that are powering the EV revolution – and this is where companies are going to face a challenge to their carefully crafted brands.

As demand spikes, EV makers will have to cast an ever-wider net to source the raw materials they need. A standard electric vehicle consists of more than 30,000 individual components, which make the EV supply chain hugely complex. Some raw materials, such as aluminium, rubber, cobalt and mica, are linked to severe environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks. Increased exposure to human rights abuses, environmental degradation and less-than-savoury governments is therefore going to be inevitable as the industry’s growth accelerates.

Using data from our Commodity Risk Service, we’ve analysed the global risk landscape for a host of materials going into EV and electric car battery production to reveal the potential risk exposure manufacturers face in existing sourcing locations and those likely to emerge as important commodity hubs in the future.

Here are some of the key things we found...

Green battery revolution brings high risk

For EV manufacturers, the risks associated with the production of lithium-ion batteries for electric car battery production are particularly striking.

As shown in Figure 1 below, seven of the primary raw materials in lithium-ion batteries – cobalt, lithium, copper, manganese, nickel, graphite and bauxite – are categorised in a number of producing countries as posing an extreme or high risk across 20 ESG issues. This should provide an instant red flag for the industry operators who will increasingly face brand damage or regulatory penalties from the slew of emerging legislation addressing supply chain issues.

Drilling down further, the single biggest area of concern is cobalt production in DR Congo. The troubled country is the leading global producer of the metal, but a multitude of labour and human rights violations, including the exploitation of up to 40,000 children, have been reported in connection with the industry. At the industrial end of the scale these risks are reduced, but cobalt from unregulated artisanal mines can, and does, find its way in to legitimately sourced raw materials. Elsewhere, lithium and copper development have spurred civil unrest and impacted the rights of indigenous people in countries across Latin America, while environmental degradation due to nickel extraction led to the closure of 23 mines in the Philippines.

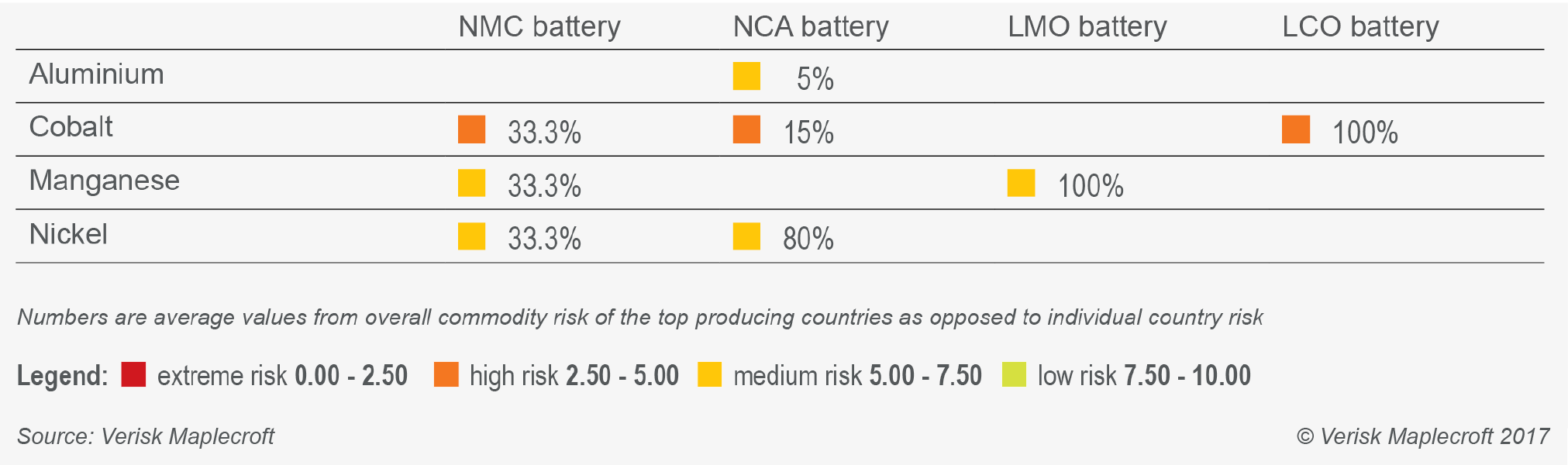

Businesses require transparent methods to identify the production level risks in the lower tiers of the supply chain. But to do this they need to not only know what raw materials are used in their products but understand each material’s unique journey, from the mine to the factory floor. This is no easy task, as illustrated by Figure 2, below: lithium-ion batteries have different risk profiles depending on the component parts of their cathodes, and these risk profiles are subject to change depending on which country the raw materials used to make electric car batteries are sourced from.

Traceability a challenge in complex EV supply chains

The number of components to trace is one problem. The other is the complexity of each supply chain. Once mined, the raw materials required by EV producers traverse an elaborate network of suppliers that can see the smelting together of metals extracted from legitimate mining operations with those from unregulated sites. Once refined and used in the manufacture of battery or automobile components, these are then sold on to multinational brands.

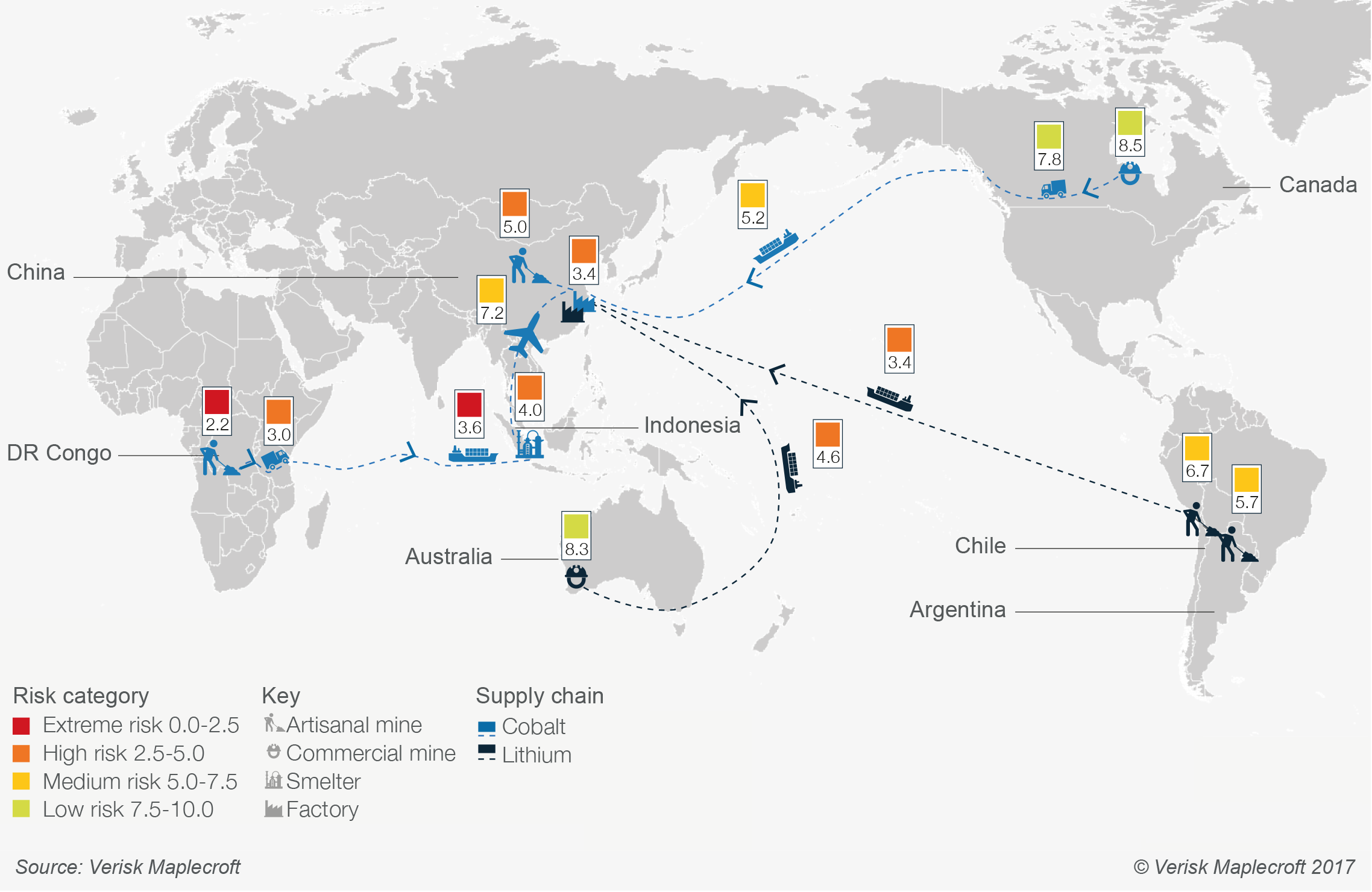

Traceability requires end-to-end analysis of the EV supply chain in order to identify risks present beyond the mine or tier 1 factory supplier. By combining our commodity data with industry data (which assess resilience and sustainability risks associated with specific sectors such as transportation and infrastructure), we can show the inherent risk present at each stage of the EV supply chain.

As illustrated by Figure 3, above, a lithium-ion battery manufacturer operating in China can be exposed to a whole range of risks: from widespread child labour in DR Congo, corruption associated with the overland transport to east African ports, to potential natural hazard events capable of disrupting smelting in Indonesia. And this is on top of the risks attached to China’s own extractive sector, including labour violations, environmental degradation, land grabs and corruption.

A big problem for the industry is that no laws or significant initiatives exist for a majority of the raw materials used in EVs. While conflict minerals mined in DR Congo are subject to a number of regulations, EV makers are sourcing raw materials from an increasing breadth of producing countries where regulations are often either non-existing or poorly enforced; this complicates the risk management process even further.

Securing future supply opens Pandora’s box of risk

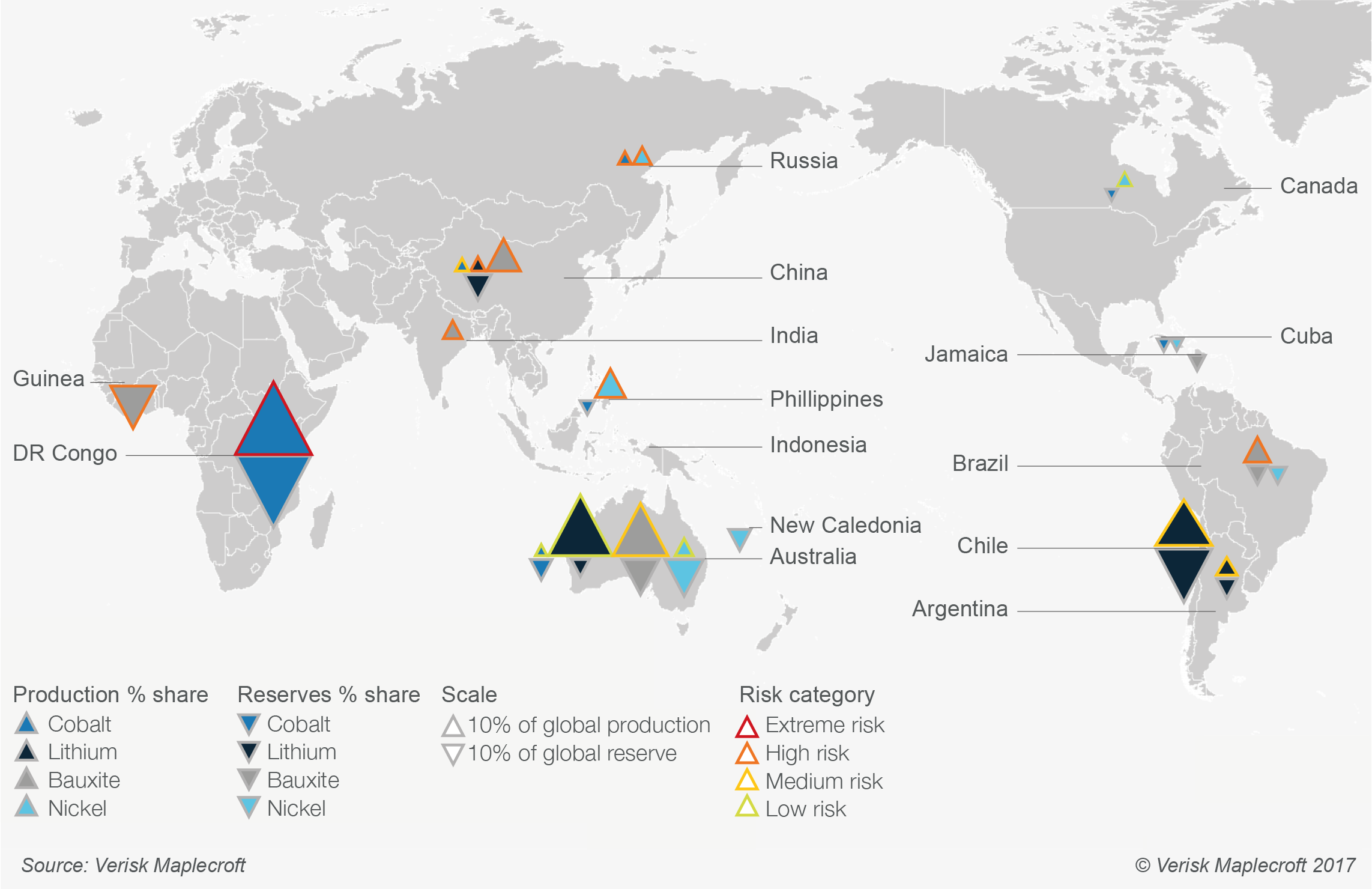

China is the top producing country for 86% of the key commodities in lithium-ion batteries. However, this is likely to change as the production of EVs accelerates, forcing businesses to turn to new source countries with large reserves of key raw materials, such as DR Congo, Russia, the Philippines and South Africa.

But the extractive sectors in these alternative sourcing countries pose some acute ESG risks. Government interference in the extractive sectors in both Russia and South Africa, for example, means that both countries receive high risk scores in our Resource Nationalism Index.

The risk associated with a shift in source country is best exemplified by aluminium. Production is moving from a relatively benign operating environment in Australia to Guinea, whose extractive sector is characterised by corruption and lax labour standards. And given the presence of both artisanal and commercial operations, it will be hard to trace where illegally extracted bauxite is being mixed with legitimately mined ores.

In order for EV producers to maintain their clean, green image, they will need to ensure that every individual component required for the manufacture of their vehicles is ethically sourced and as untarnished as a new vehicle rolling off the production line. As the sector promotes sustainability and an eco-friendly image, the potential for being linked to extremely damaging ESG incidents should be a major concern.

More information about our commodity risk analytics can be found here. Call us on +44 (0)1225 420000 or email info@maplecroft.com to see how our data can help your company.