Economic issues to dominate MENA politics in 2021

by Hamish Kinnear and Torbjorn Soltvedt and Anthony Skinner and Niamh McBurney,

Money, money, money

That is the name of the game for the Middle East and North Africa in 2021. Government revenues - their stability, the ability to spend money, the ability to generate money - are at the heart of regional concerns for this year, from whether oil producers can collect enough to diversify their energy supply and provide jobs, to Iran re-emerging as a major oil exporter.

Questions of production and political choices abound

The dual shocks of 2020 have compounded the structural issues laid bare in the mid-2010s from which no MENA country emerged unscathed.

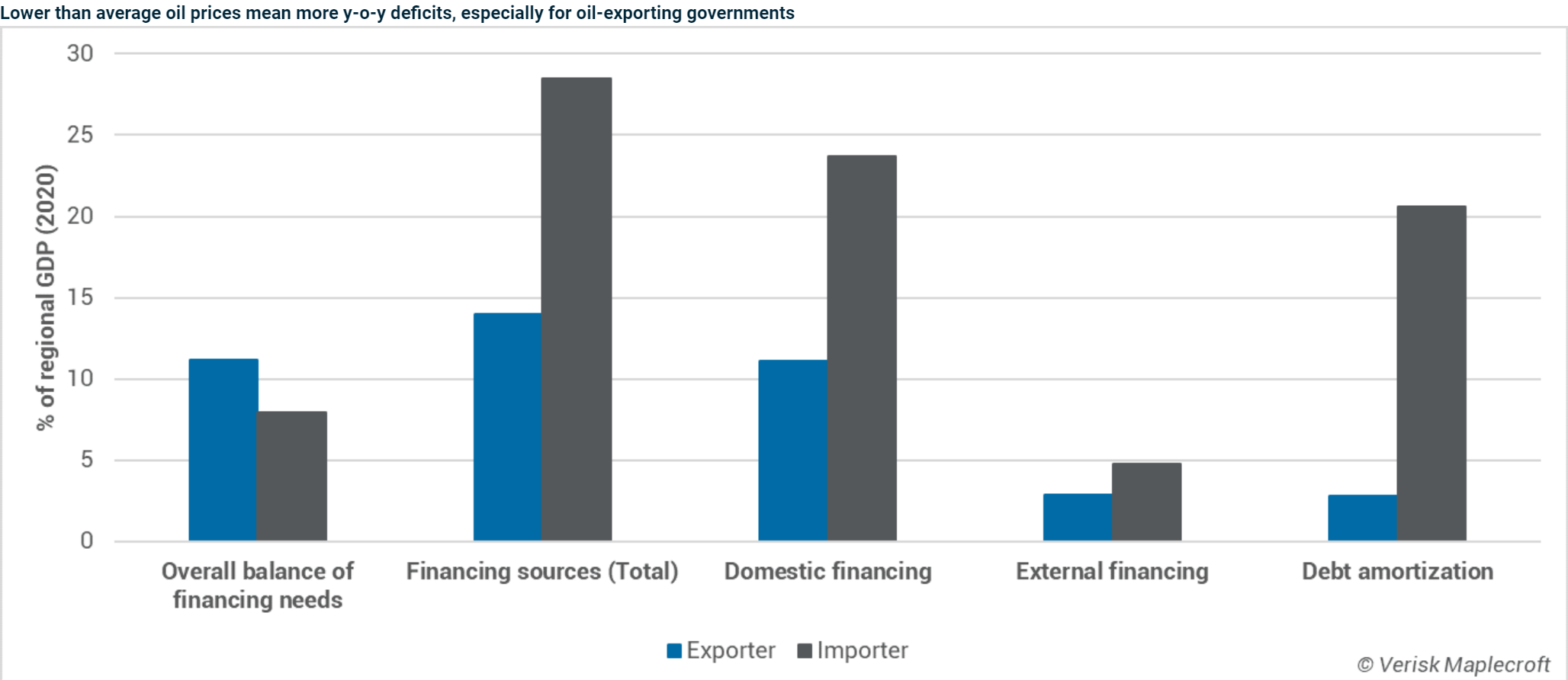

For oil exporters, debt accumulation combined with growing fiscal deficits to fund diversification programmes and social welfare means there are difficult policy choices to make in 2021. Countries across the region face the challenge of funding the costs of the energy transition (see below) even as gross revenues stall. Some countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, will be able to secure oil revenue stability through increasing their market share. But the region’s oil producers will become a two-speed group as others miss out, and this will increase the need to tap capital markets further to fill the gap.

For the importers, a common denominator of 2020 is the shock to tourism sectors across the region. Although debt amortization rates far outweigh those of exporters, this is overwhelmingly due on debt recycled through the domestic banking system. As 2020 proved in Lebanon, this cycle can prove fatal without confidence from the international community.

The whole region faces the dilemma of increasing debt, whether domestic or foreign, and pressure to produce fresh growth. Taking the countries sampled in the IMF data below from our Political Stability Index, we reach a median of 5.38 / 10.00 for the oil importing countries, and 6.37 / 10.00 for oil exporters. Both in our medium risk category, the two groups are approaching an inevitable future of fiscal scarcity rather than plenty, setting the stage for a challenging year ahead.

Swift US return to the JCPOA remains unlikely

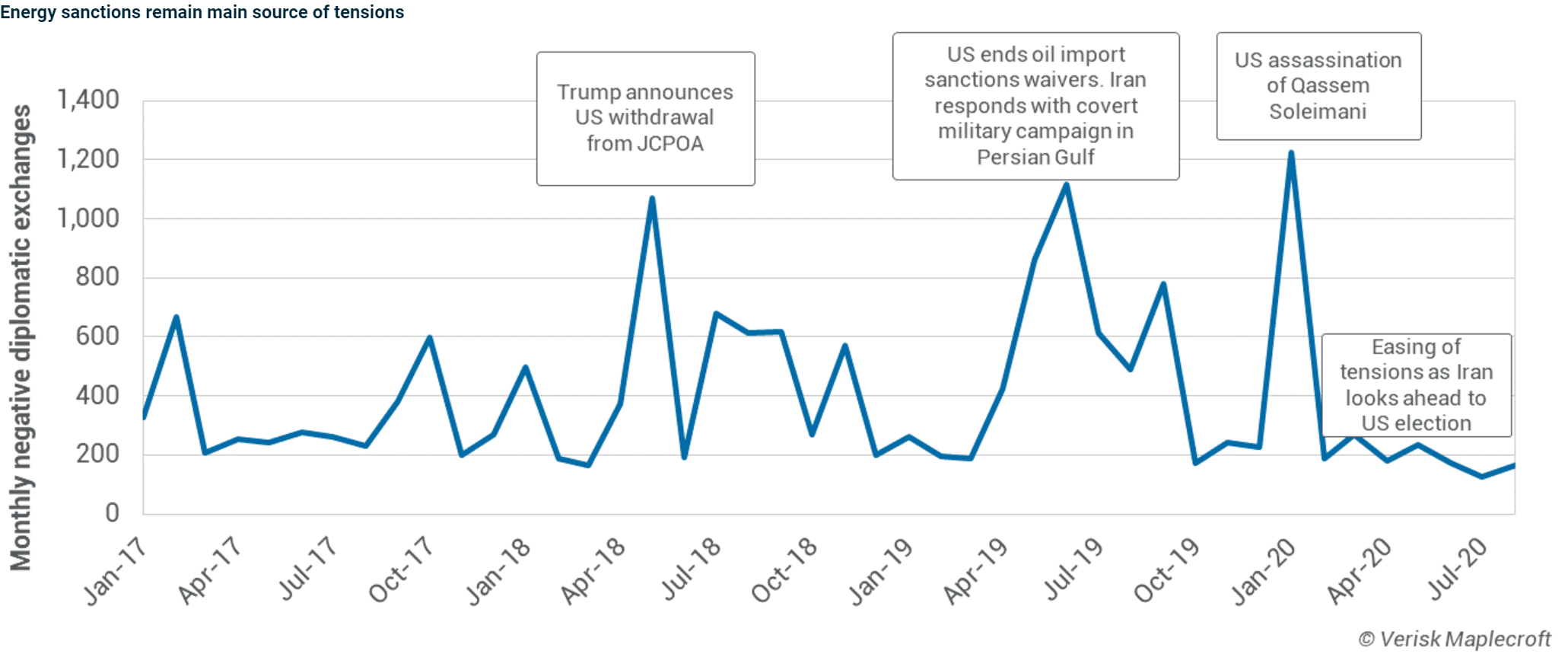

Tensions between Iran and the US will remain a defining characteristic of the regional geopolitical landscape during 2021.

Both the Biden administration and Iranian president Hassan Rouhani have expressed a wish to return to the framework of the JCPOA. But with both sides expecting the other side to move first, there is no clear path toward a US return to the agreement and a lifting of energy sanctions.

The gap between the two sides is widening rather than narrowing. On the Iranian side, efforts to ramp up the country’s nuclear programme continue apace. After gradually reducing its compliance with the JCPOA since mid-2019, Iran’s breaches of the agreement have become more serious in 2021.

The incoming US administration has made it clear that “Iran is out of compliance on a number of fronts” even as the US remains a non-signatory. The prospective intention by the US to go beyond the framework of the JCPOA and incorporate non-nuclear issues – including Iran’s regional posture and ballistic missile programme – has been dismissed by Iran. Both sides stress the urgency of the situation but there is no clear route to restarted negotiations before Iran’s presidential election in June 2021.

Regional security hangs in the balance

Given the impasse, the most likely scenario is that both countries will have to look for more informal ways to ease pressure and lay the groundwork for talks at a later stage.

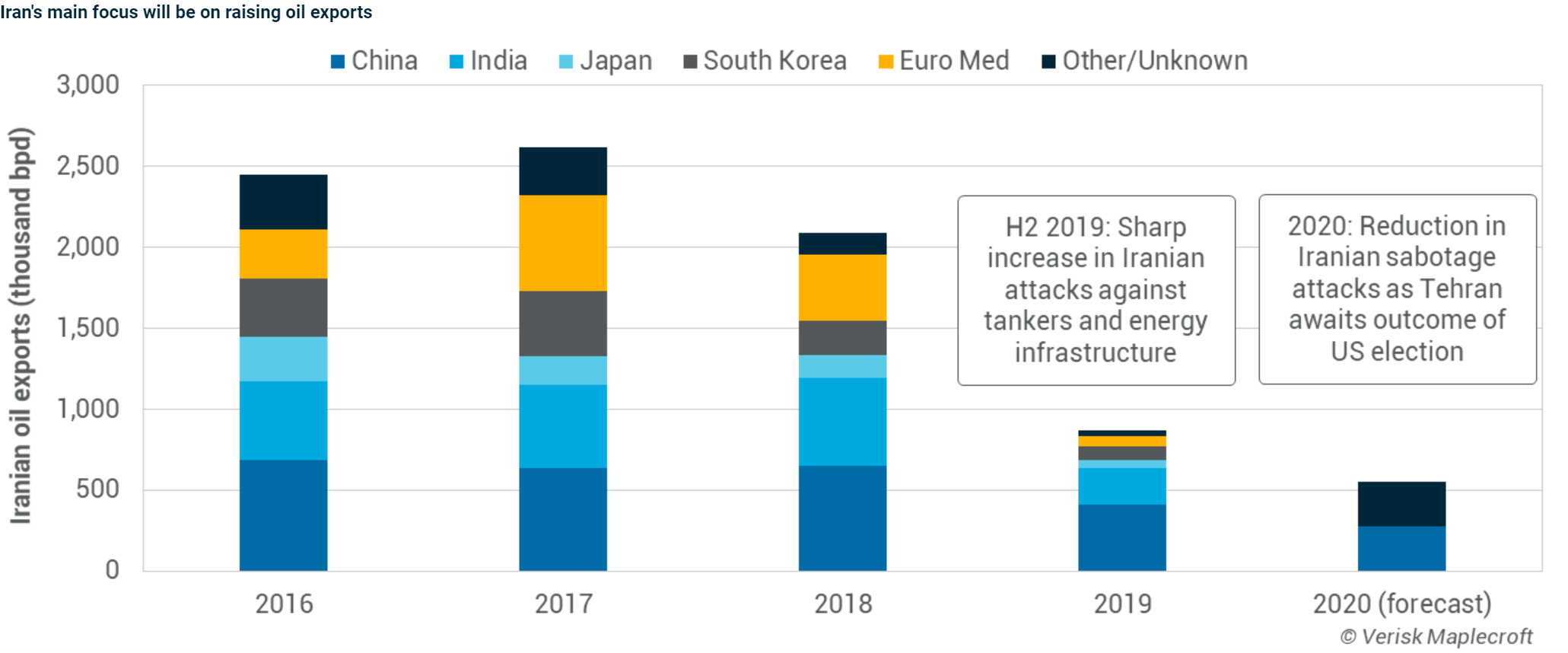

With oil at the centre of the rising tensions over the last 20 months, even a limited easing of US pressure has the potential to diffuse tensions. The Biden administration is unlikely to enforce sanctions as vigorously as the Trump administration. China perceives the risk of increasing oil imports from Iran as lower under Biden; likely to be a factor in considerations as the US and China look to improve ties, this reveals yet another layer to the geopolitical complexity of the Iran nuclear issue.

Although the Iranian authorities have not provided figures for its December 2020 and January 2021 oil exports, the country’s oil ministry stated on 22 January 2021 that volumes are rising “significantly”. Independent trackers have echoed this, with some suggesting that exports have risen above 1 million bpd.

The extent to which the US will allow Iranian oil exports to stabilise to, if not above 1 million bpd will be crucial for a positive trajectory for regional security, and the prospects of a more formal agreement in the coming years.

COVID-19 pressures driving protests but most regimes remain resilient

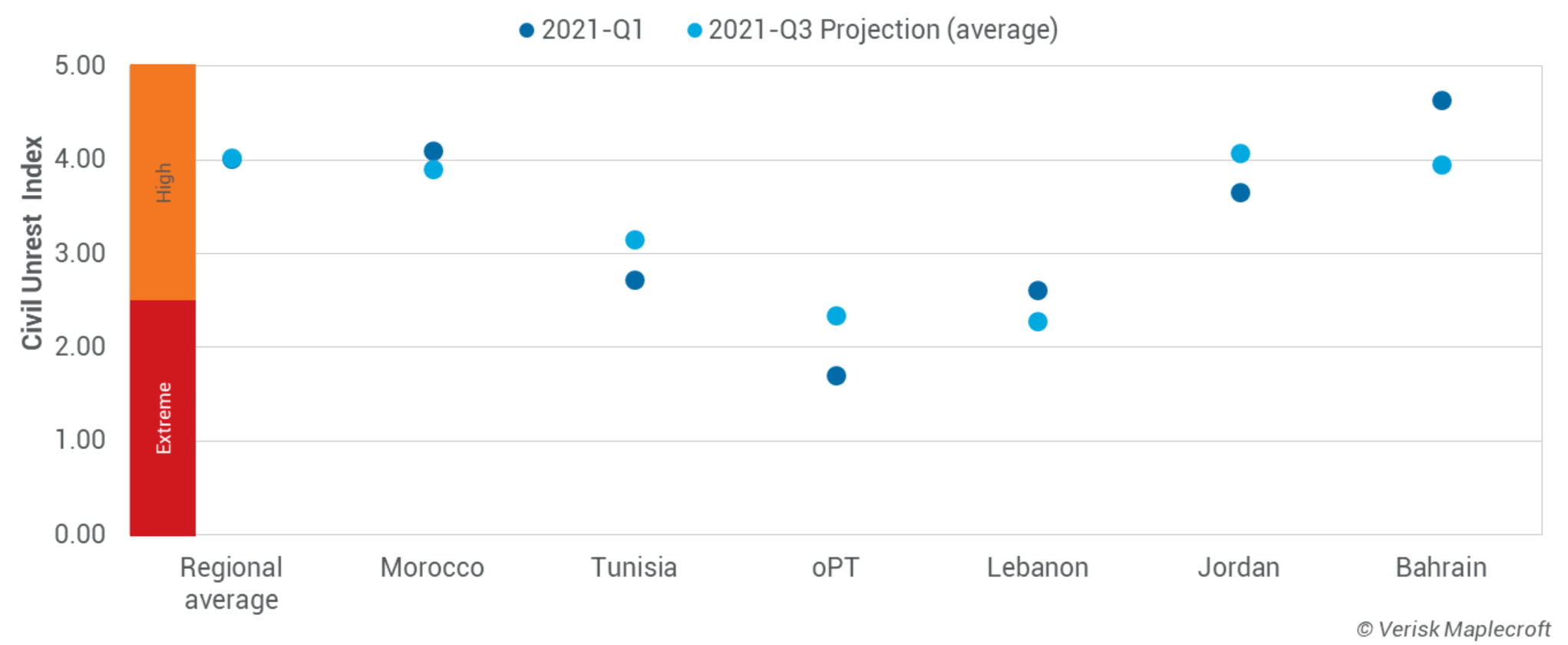

The threat of civil unrest across MENA will persist in 2021 at least partly because of the continuous toll COVID-19 is taking on regional economies. While protests are propelled by an array of public grievances – including corruption and police brutality – pandemic-driven economic pressures will remain persistent drivers. The World Bank estimates that the pandemic moved 2.8 million people in the region into extreme poverty.

In our Civil Unrest Index, the average regional scores for 2021-Q1 and for the six-month projection of 2021-Q3 are almost identical at 4.01 / 10.00 and 4.03 / 10.00 respectively. This highlights how the pandemic has reinforced structural challenges across the region, and intensified existing public anger over already rising unemployment and living conditions, rather than creating new risk factors. This is clearest in protests in Tunisia, Morocco, Algeria, Lebanon and Iraq carrying over into the new year.

Of the 18 MENA countries in our projections universe, 10 receive a worse score for 2021-Q3 compared to today. The scores of only seven improve. MENA’s continued vulnerability to civil unrest is real: two-thirds of all countries in the region classify as high or extreme risk for 2020-Q3. Globally, less than 12% of countries and territories scored in our Government Stability Index are projected to be in the high or extreme risk categories in their six-month projections.

However, the centres of power in MENA countries which remain politically volatile such as Libya, Algeria and Lebanon will need to remain vigilant.

Steadier oil prices to help energy transition in Middle East

Oil prices are stabilising as the vaccine roll-out proceeds worldwide and East Asian demand begins its return to pre-pandemic levels. This is welcome news for oil producers in the Middle East, but it risks a return to a familiar pattern; promises of economic reform made during the downturn prove elusive as oil revenues tick back up.

In one major respect, things are different this time. The pandemic has brought energy transition policies to the forefront in the major demand centres of Europe, the US and Asia, although our analysis of global policies suggests the shift will be slow and steady rather than rapid and radical. Hydrocarbon demand will therefore continue for decades to come and, critically, cheaper extraction costs will give Middle East producers a competitive edge during the transition phase.

For that strategic potential to be maximised, Middle East oil producers will need to slash domestic consumption to maximise exports – with countries such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE already pursuing this path. Heavy investment into renewables and hydrocarbon alternatives like hydrogen is required, and the stabilisation of oil prices could be the perfect opportunity. It could also act as an incentive to non-oil producers like Jordan, which has traditionally relied on cheap and readily available supplies from its neighbours, to transform their energy base and cut import costs.