Why it matters

Companies failing to get to grips with the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (widely known as TCFDs) may not have much time to get it right. Leaving investors unsatisfied by not disclosing the required information threatens a company’s creditworthiness, while regulators are keen to make disclosure mandatory.

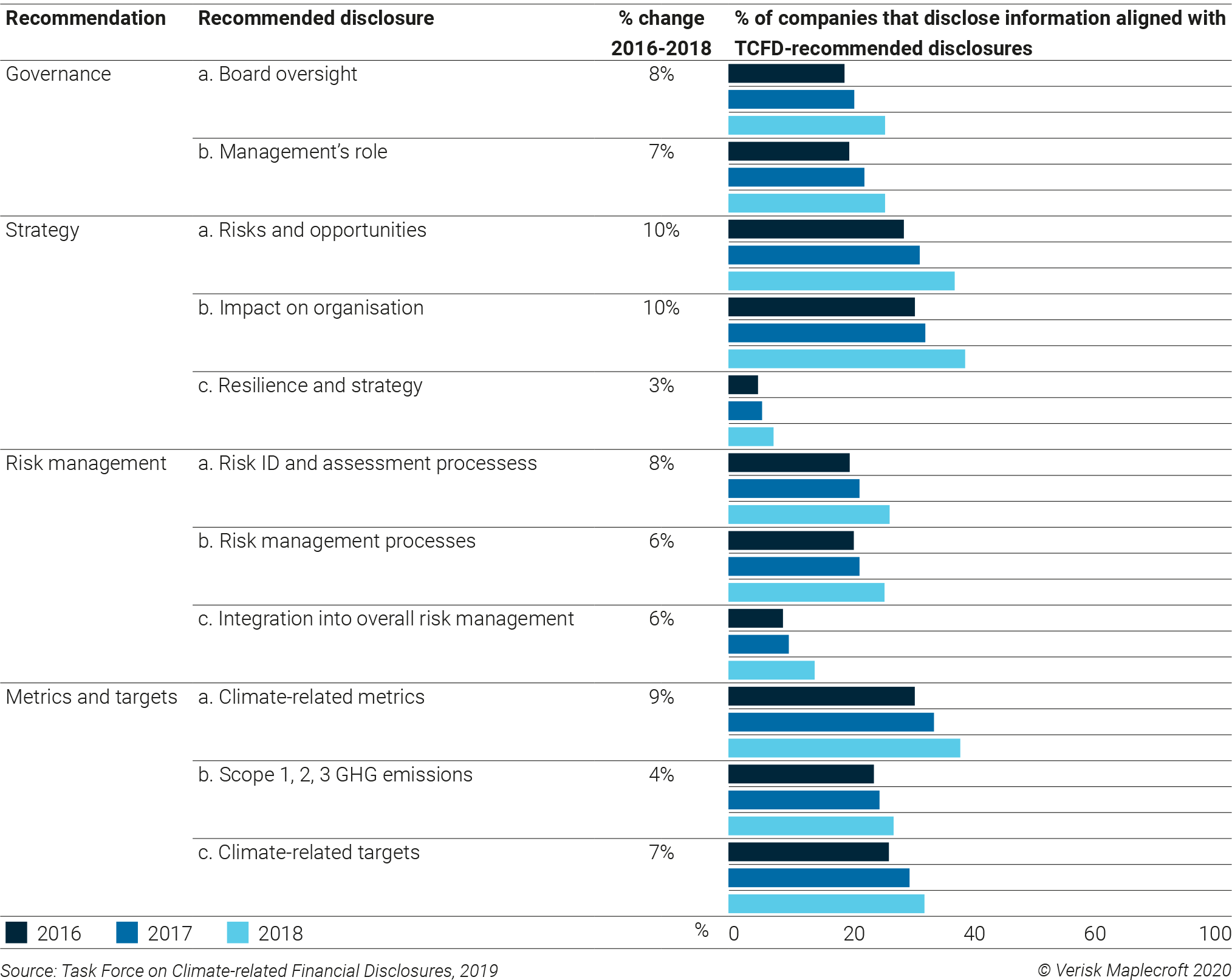

As shown in Figure 1, the ‘disclosure gap’ between investor expectations and the climate risk information companies were disclosing (flagged in last year’s Outlook) is closing slowly. But companies are still struggling to align with the TCFDs, with elements of scenario analysis and integrating climate into management strategies proving to be the biggest roadblocks.

We see two main reasons for this. First off, scenario analysis is difficult and time consuming. The TCFDs ask companies to “describe the potential impact of different climate scenarios, including a 2ºC scenario, on the organization’s businesses, strategy, and financial planning.” But which scenarios to choose? And how do you then translate those into financial impacts? And, finally, how do you integrate the results – which could appear uncomfortably close to guesswork – into strategy and planning?

Second, there’s the epidemic of survey fatigue. There is a whole universe of different standards out there, each asking for information that takes a chunk of time to prepare. Rightly, executives will question why all these resources are being directed away from core business activities, and whether TCFD alignment should take priority over other reporting benchmarks.

At the same time, the prospect of disclosure standards becoming mandatory increases the urgency for companies to get it right.

Watch out for

Organisations unable to answer the questions investors are posing will start to find it affects their financial credibility. It may be too soon to suggest that investability or creditworthiness hinge on blemish-free TCFD disclosures, but we know that ratings agencies are already using climate disclosures and strategies as a window into wider corporate governance.

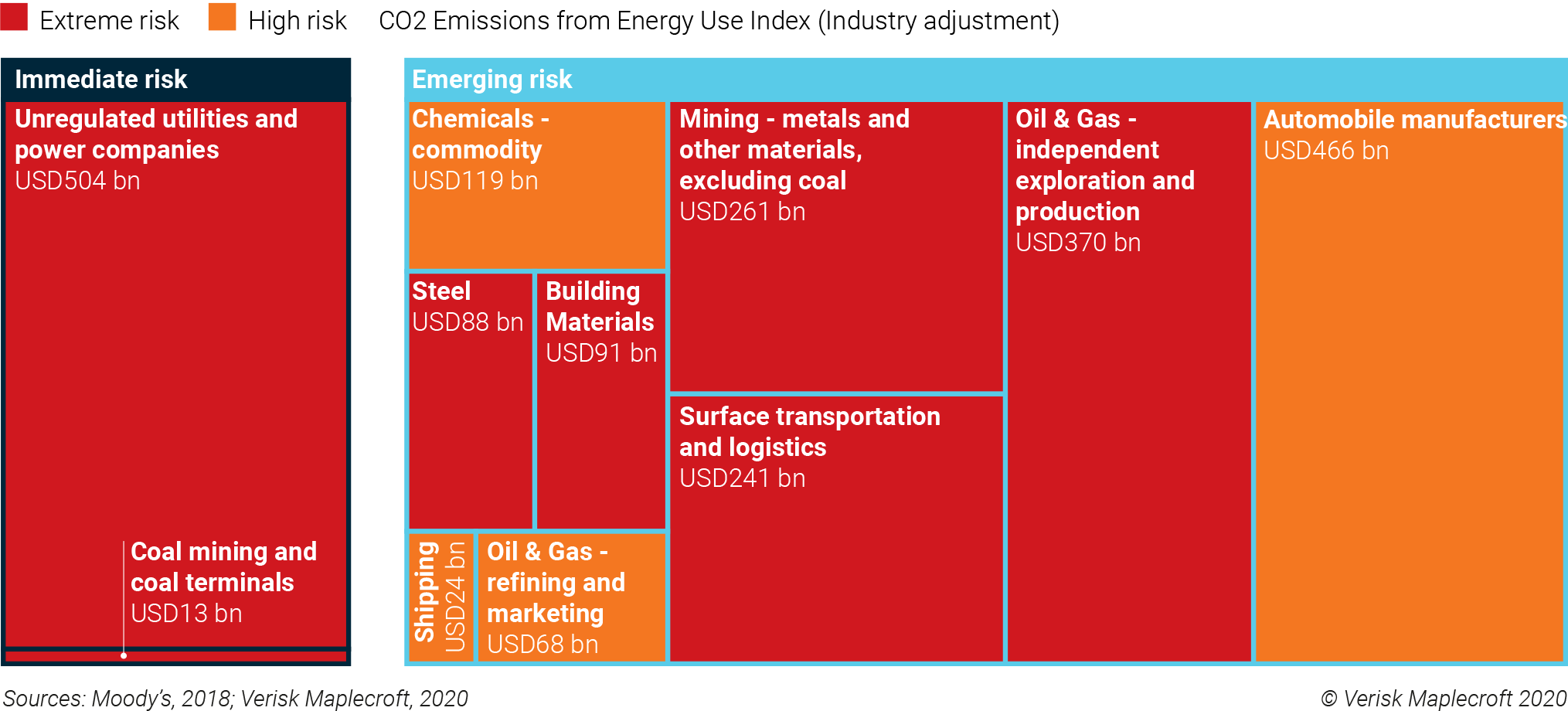

The fact that Moody’s reconsidered ExxonMobil’s AAA rating – alongside that of other companies – over this past year shows a clear steer that the scale of a company’s efforts to meet its global carbon targets will impact its creditworthiness. And this risk extends beyond fossil fuel companies to those that do not necessarily emit a lot of carbon but instead facilitate those that do. In 2018, Moody’s identified 11 sectors with a combined USD2.2 trillion in rated debt that were at risk of carbon-related downgrades. As our industry data highlights, all of these sectors are high or extreme risk for emissions in the US.

Even if percolating credit risk across 2020 and beyond doesn’t convince the C-suite to take TCFDs seriously, the potential for mandatory disclosures certainly should. In October 2019, former Bank of England chief Mark Carney, who helped launch the TCFD in 2015, warned that corporations have two years to improve the quantity and quality of their climate risk disclosures before global regulators start to impose rules; New Zealand started consulting on a mandatory regime less than a month later. The UK, Australia, Canada, France, Japan, and the EU are not far behind.

What’s more, TCFD reporting will become a requirement in 2020 for signatories of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), while other reporting frameworks like CDP are incorporating TCFD questions. So, one way or another, leading companies will start to align with the TCFDs this year.

Download our Environmental Risk Outlook webinar recording

Next steps

Putting in the time to get scenario analysis right will go a long way to tackling some of the difficult questions relating to climate-related risks and impacts raised earlier on. Soliciting feedback from investors on what information they need to know can help firms to concentrate on what is material and to streamline ESG disclosures. Plus, this process will feed into scenario analysis.

The TCFD recommends organisations analyse a 2ºC scenario and at least one more. This could be business as usual, in line with a particular country’s Paris Agreement pledge, more intense physical risks, or increasing climate activism and litigation, depending on feedback from investors. Concentrating efforts on a specific asset or business activity, ideally one of interest to investors, would be a good first step for calculating financial impact before expanding across the company.

Finally, leveraging and adapting existing management plans to take account of climate risk is the first step towards fully integrating the results of scenario planning into strategy. Incorporating accurate and granular data throughout the whole process adds consistency and credibility, while looking to best practice examples across industries reduces the fear factor and helps turn scenario analysis from a burden into a truly effective tool.