COVID-19 pandemic is last straw for large African economies

by Ed Hobey-Hamsher and Alexandre Raymakers and Indigo Ellis,

Measures to contain the progression of coronavirus are already exacerbating underlying health issues in major African economies. The Kenyan, Nigerian and South African economies are unlikely to weather the reduced growth that efforts to reduce the immediate number of COVID-19 cases necessitate. We expect a recession to worsen in South Africa, and Nigeria and Kenya to fail to avoid falling into recession by Q4.

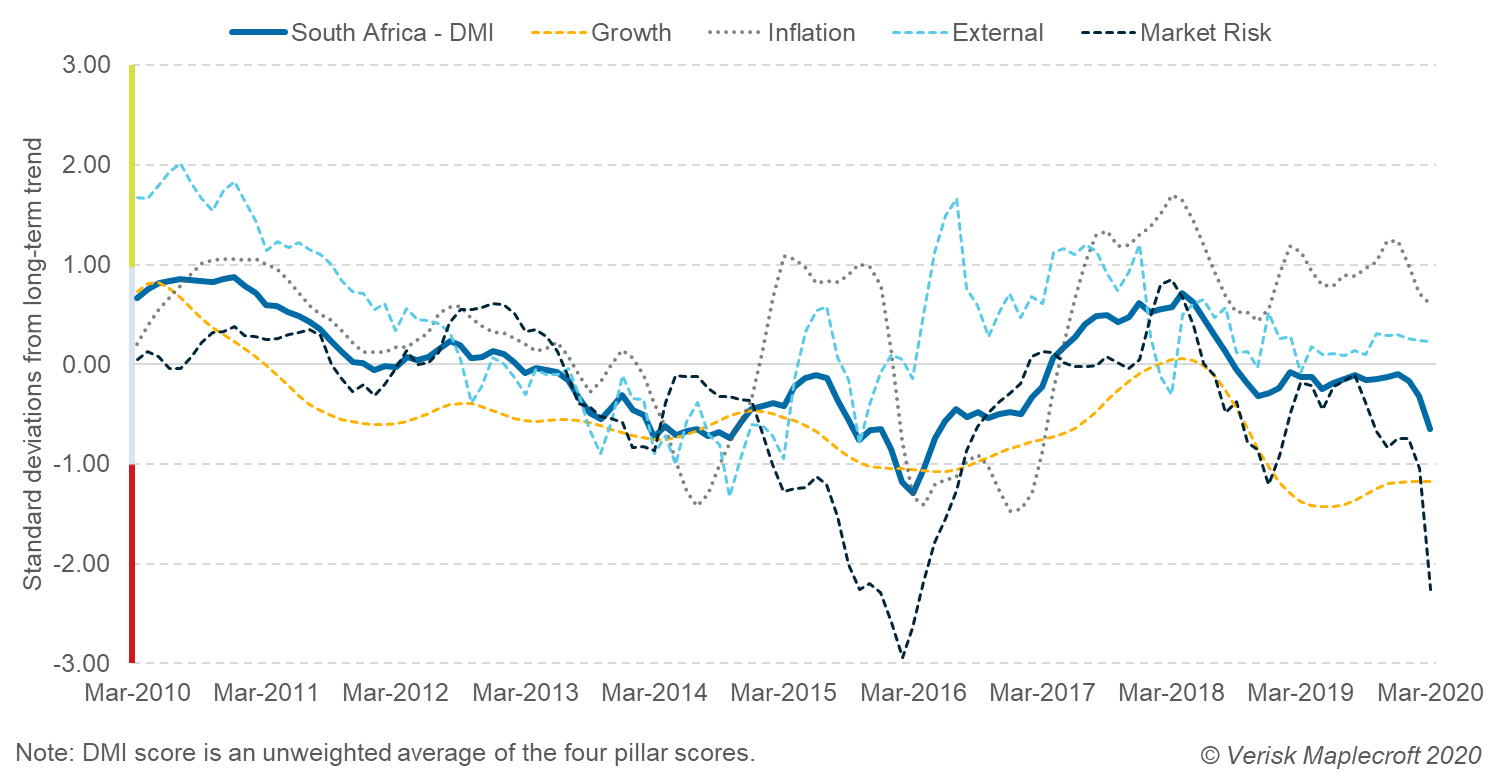

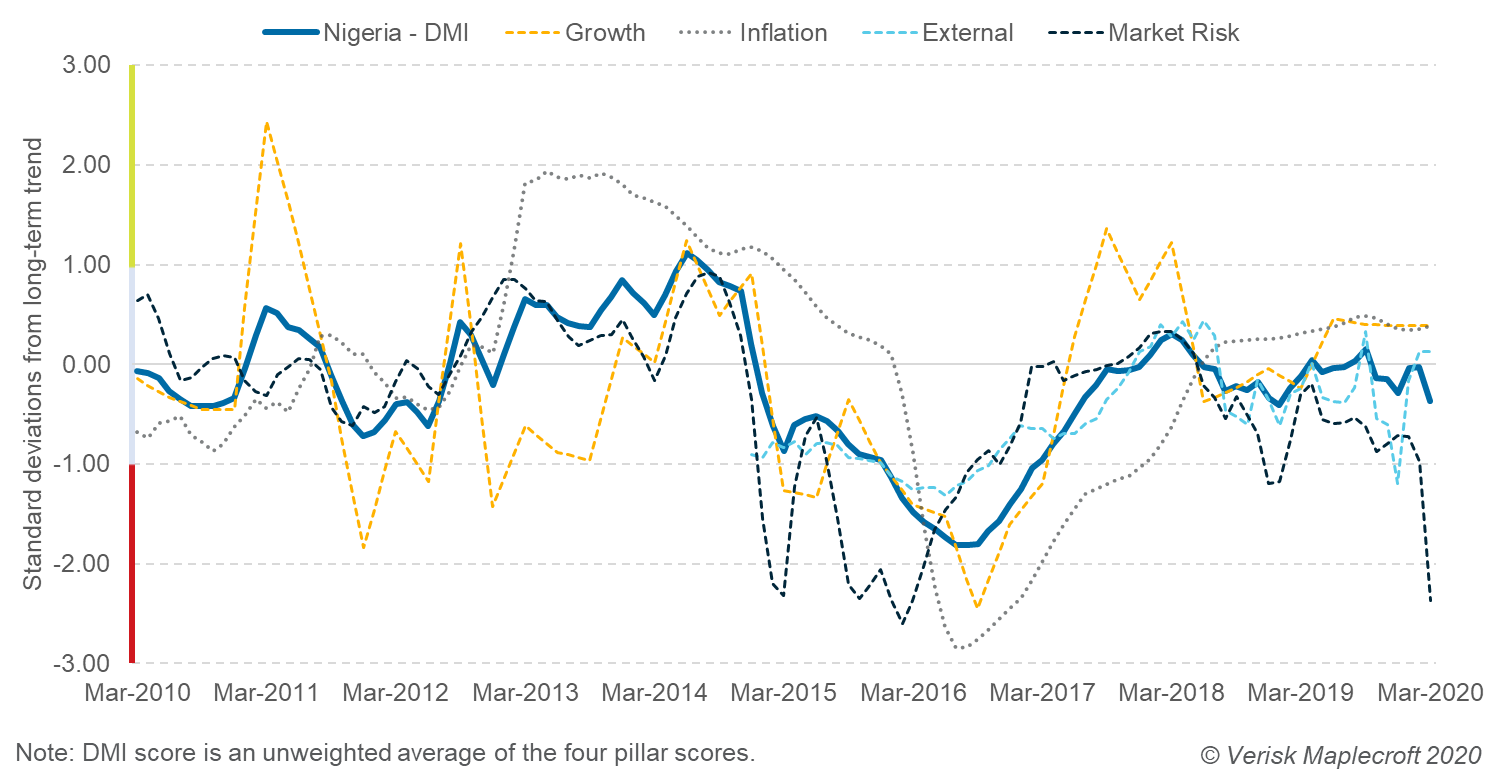

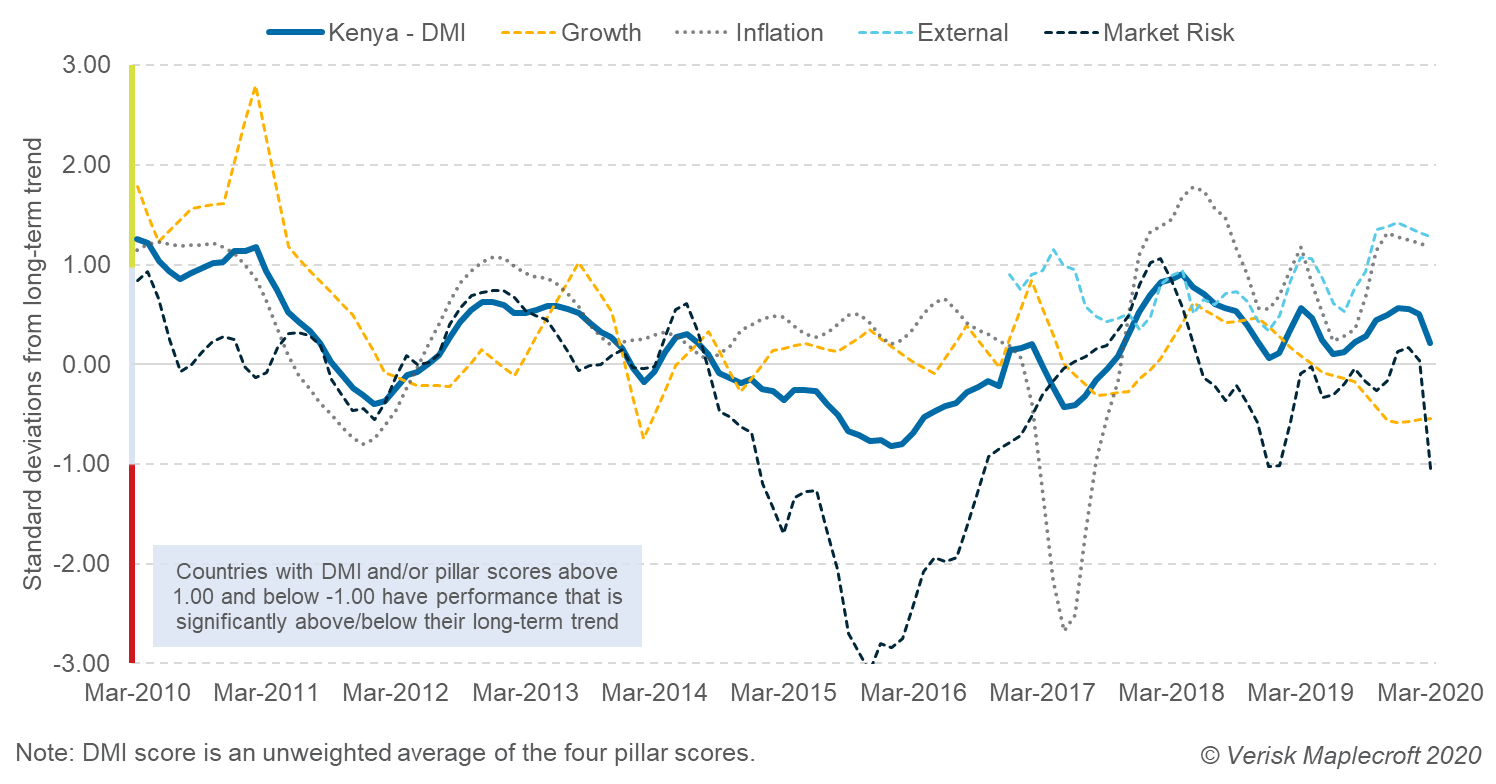

Investors are displaying massive declines in confidence in pricing Nigerian, South African and Kenyan assets, as shown in the Market Risk Pillar of our Dynamic Macroeconomic Index, where each country is showing (see charts below) extreme falls on the preceding month. This pattern will continue until at least July 2020.

View our case studies to find out how we can help your business

Lack of options at South Africa’s fingertips ensure inevitable economic malaise

South Africa fell into its second recession in two years in early March 2020 as the effects of rolling blackouts and corresponding reduced economic output in 2019-Q4 came to light. Since then, the meltdown associated with the coronavirus crackdown in South Africa means that finance minister Tito Mboweni’s 2020 budget, issued on 26 February, and greeted with relative warmth by investors, must now be scrapped. Mboweni has pledged 2-3% of GDP for the coronavirus response, including implementing a state of emergency.

The budget’s assumptions of 0.3% growth for 2020 and a budget deficit of 6.8% are now impossible to achieve. A sharp 100bp cut to the interest rate on 19 March, from 5.25% to 6.25%, is unlikely to be enough to stimulate growth. It would require a large amount of issuance to balance the gap, and South Africa doesn’t have the policy options to play with.

We expect economic output to drop by around 10% quarter-on-quarter in Q2 on the effects of the coronavirus, including reduced tourist numbers.

We expect the Treasury to scale back on its plans to cut the public wage bill considering the inevitable job losses that coronavirus will have. While the impact will slow down the inevitable slide towards South Africa’s loss of its last investment-grade rating at Moody’s, which had been set to be reviewed in early March, South Africa will not hold on for long.

Collapse in oil prices likely to force devaluation of naira in Nigeria

The collapse in oil prices, linked to both the global OPEC+ battle and to COVID-19, will drastically slow the Nigerian economy. It was already experiencing a lacklustre growth rate of around 2%. As highlighted by our Dynamic Macroeconomic Index, we expect growth to follow Nigeria’s market risk performance and drop significantly below Nigeria’s 2-year and 10-year average into April 2020 (see chart below).

The sharp drop in oil prices has forced the Buhari administration to entirely review its 2020 N10.59trn (USD35 billion) budget. The Nigerian government is expected to trim at least N1.5 trn from its budget and benchmark oil prices at a worst-case scenario of USD30 bpd. Furthermore, it has announced that it will cut capital expenditure by 20% and initiate a hiring freeze across the federal government. The government decision to scale down its capital expenditure will likely curtail the government’s ambitious infrastructure plan but enable it to meet Nigeria’s debt repayment obligations.

The Government added that it will maintain its production target of 2.18 million bpd. However, considering the current weakness in international demand for oil, it is doubtful that the Nigerian government will be able to squeeze much more revenue from its oil production.

The Government only has limited financial muscle at its disposal, with USD22 billion of the previous budget funded by domestic and international loans. Attempts to raise revenue by raising taxes will likely be politically difficult as the government already increased VAT rates from 5% to 7.5% in January 2020. We therefore expect the Buhari administration to fund most of this modified budget by widening its fiscal deficit, further heightening worries that Nigeria overall debt levels will become unsustainable.

Learn more about our Mining & Metals Solutions

Although the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has insisted that a devaluation of the naira is not currently being considered, its decision to merge its multiple exchange rate regime into a single exchange rate amounted to a 15% devaluation of the naira. We expect that the naira will be further devalued by 2020-Q3. Since June 2019, the CBN has burnt through a quarter of the country’s foreign reserves to stabilise the naira.

In a period covering January 1 to March 5, the bank recorded a further decline of USD2.3 billion from USD38.59 billion to USD36.2 Billion

The bank is likely to continue going through its foreign currency reserves and opt for some capital controls but will inevitably accept a devaluation as it did in 2016. A weaker naira would be a boost to government revenues as it would allow dollars from oil revenues to be converted to naira at a much higher rate. But this will be a setback for the Buhari government that has made keeping the naira stable a pillar of the president’s long-term ambition to revive local industry and reduce the country’s dependency on imports.

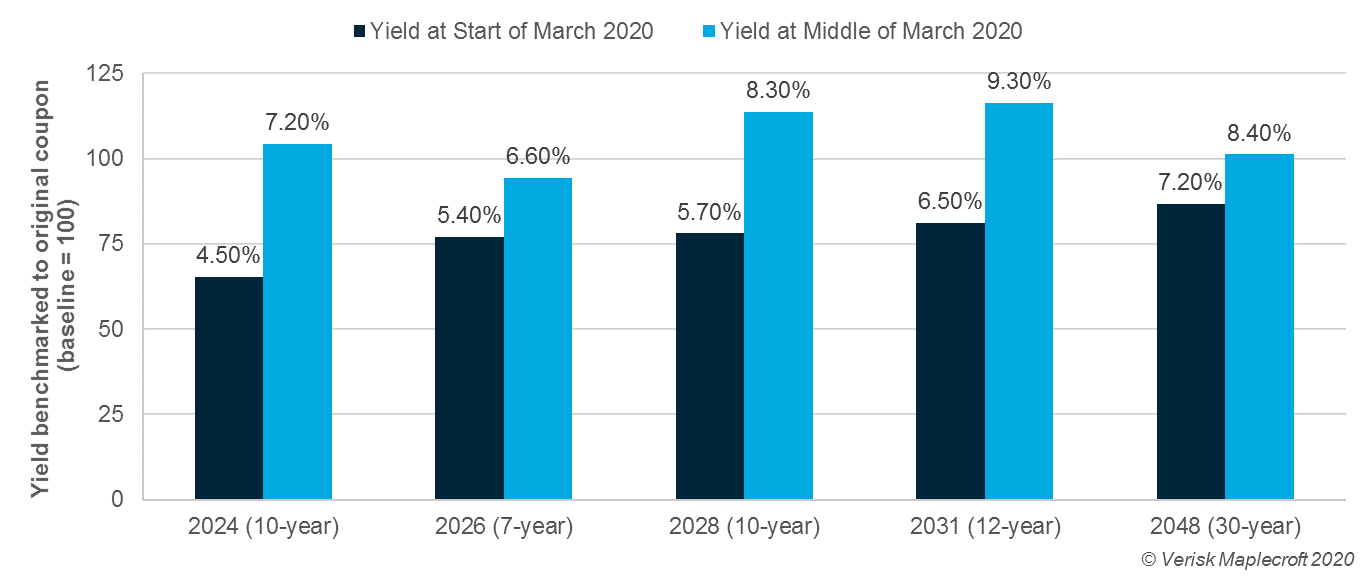

COVID-19 likely to delay political referendum and Eurobond issuance in Kenya

The COVID-19 outbreak makes it less likely that Kenya will launch a Eurobond to finance the forthcoming Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) referendum. The immediate impact of not holding the BBI referendum will exacerbate already tense relations between President Kenyatta and now co-opted former opposition leader Raila Odinga. Odinga views the referendum as a precursor to the creation of the office of prime minister in which he could install himself. We project that tense relations between Kenyatta and Odinga over the issue of presidential succession in 2022 contributes to a poor government stability outlook over the 6-month and 2-year period. In the longer term, however, short-term political instability will have positive economic repercussions - less non-concessional borrowing improves Kenya’s debt sustainability outlook.

Kenyan Eurobond yields increased during the first two weeks of March as portfolio investors began to factor in the risk of coronavirus reaching Kenya, and the progress of locust swarms sweeping the nation.

A disruption of imports from China and South Korea will force local merchandisers to source from alternative, and likely more expensive, markets increasing demand for dollars. Currency pressures and depressed consumer confidence will be worsened by reduced remittances due to the global economic slowdown. Foreign investors are net sellers as Kenya follows the global trend of portfolio investors seeking safer assets. Foreign investors exiting the market will further require dollars, contributing to currency volatility.

But the shilling will be supported by high levels of foreign exchange reserves (over 5 months of import cover) and an interventionist Central Bank of Kenya (CBK). It is likely that the CBK will make a marginal cut to rates at the next monetary policy committee meeting on 23 March to increase liquidity for importers, thereby reducing the price of local goods.

The subdued sectoral economic activity will hit GDP growth: manufacturing and fast-moving consumer goods; tourism, aviation and hospitality; agriculture and horticulture; and financial sector.

Political risk is still the primary determinant of business activity in Kenya. In the middle of an election cycle, 2020 should have been peak of economic growth but has been hampered by factors beyond the control of government or central bank - locusts and COVID-19.