Corruption risks climb in 88 countries, key sourcing economies among worst affected

by Jess Middleton,

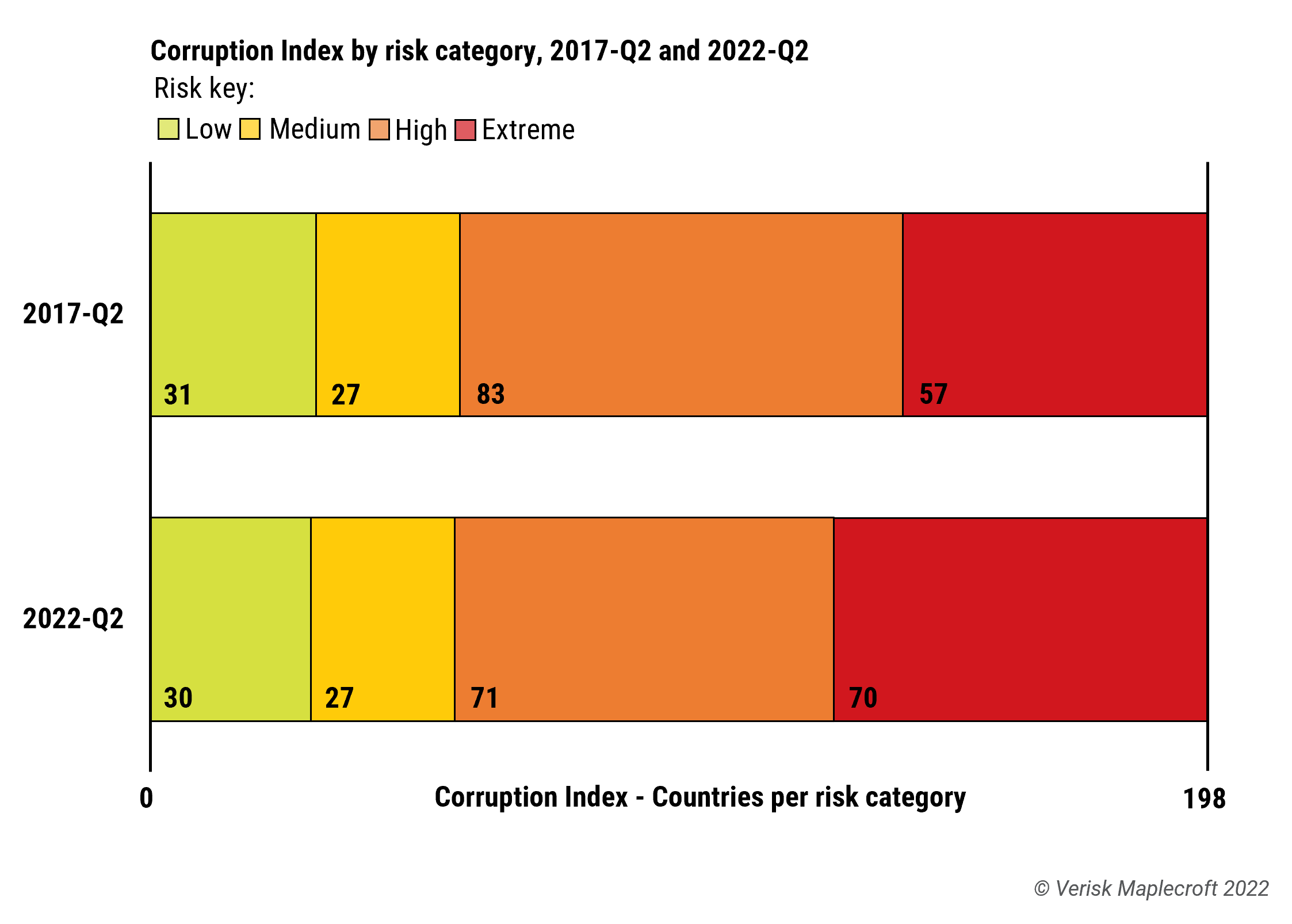

The threat posed by corruption to businesses around the world is on the rise. The number of countries rated extreme risk in the latest edition of our Corruption Index has swelled to 70, up from 57 in 2017 (see Figure 1). Our data shows that risks are prevalent or rising across all regime types, from one-party states and military dictatorships to key emerging markets and major democracies. All told, corruption risks have risen in 88 countries over the past five years.

The specific factors driving corruption vary from country to country, but the global uptick has been aided by the confluence of two positive trends in the fight against graft: the evolution of whistleblower legislation and the onset of the digital age. In this climate, governments have been forced to digitise documents, making them more accessible to investigative journalists and activist citizens. Suspicions and allegations can then be rapidly disseminated into the 24-hour news cycle.

“This trend should set alarm bells ringing for global businesses,” says Jimena Blanco, Chief Analyst at Verisk Maplecroft. “Organisations need to ensure they have robust policies in place to protect against the reputational and economic damage that comes through association with corruption, which is now being uncovered and exposed on a more frequent basis.”

Corruption risks prevalent within key emerging markets

Unsurprisingly, the 10 countries rated highest risk on the Corruption Index - which assesses the frequency and severity of corruption in 198 countries alongside the strength and independence of their anti-corruption laws, and the effectiveness of their implementation - are primarily authoritarian states and fragile democracies. These include international pariahs Syria (ranked 1st for corruption risks), North Korea and Eritrea, as well as Equatorial Guinea, Somalia, Lebanon, Laos, Libya, South Sudan and Venezuela.

But zooming out to take a wider view of the data reveals that corruption poses an extreme risk to business in several countries that are either increasingly vital or already key players within the global economy. These include Bangladesh (ranked 30th), Nigeria (36th), Vietnam (43rd), Thailand (48th) and China (51st). Notably, Brazil, Mexico and Cambodia have all slipped into the extreme risk category of the Index since 2017-Q2.

In Brazil (ranked 69th in the latest edition of the Index, up from 65th in 2017 but within the extreme risk category because of a worsening score), Jair Bolsonaro has largely failed to deliver on the anti-corruption agenda that aided his electoral success in 2018. Faltering trust in the achievements of previous anti-corruption initiatives, coupled with a lack of political drive in the run up to Bolsonaro’s troubled bid for re-election, mean that further efforts to tackle corruption have been placed on the back burner.

It is a similar story in Mexico (ranked 52nd, down from 70th in 2017), where corruption allegations involving close associates of President López Obrador have cast a pall on the anti-corruption mantra that underpinned his victory in 2018. A limp response to allegations made earlier this year, centred on the lavish lifestyle of Obrador’s son, underscored wider concerns around the president’s commitment to combatting graft.

Elsewhere, the implication of several members of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party in scandals involving smuggling and the expropriation of land has contributed to Cambodia’s 52 position fall in the Index rankings, down to 22nd from 74th five years earlier.

Major democracies not immune to corruption

While corruption thrives in the absence of good governance, our data shows that stable political systems aren’t immune to climbing risks.

Indeed, 43 countries have recorded a significant decline – defined as a decrease of 0.5 or more - in their Corruption Index score since 2017-Q2. This includes 26 countries that receive a low or medium risk rating on the latest edition of our Governance Index, which assesses the extent to which authority is exercised in an accountable, transparent and inclusive manner in accordance with the rule of law (see Figure 2).

This includes the US, where a deteriorating score translates into a decline from 183rd to 171st place in the Corruption Index rankings, highlighting the disregard for customary rules that characterised the Trump administration.

Criticisms levied at Trump by anti-corruption watchdogs included his failure to appropriately distance himself from his myriad business interests. The former president also notably watered down the conflict-of-interest restrictions typically placed on executive employees.

Discrepancies between states regarding the scope of anti-corruption legislation and the resourcing of oversight bodies can partly explain the US’s lack of improvement on the Index under Biden.

Corruption risks are climbing on the other side of the Atlantic too. The UK has fallen from 192nd to 176th place in the rankings, driven primarily by the Johnson government’s low tolerance for scrutiny and a tendency to disregard the countervailing institutions that sit at the heart of British democracy. Also noteworthy is the fact that Rwanda has seen the largest deterioration on the Index since 2017, further calling into question the UK’s controversial decision to deport asylum seekers to the country.

Elsewhere in Europe, the sharp deteriorations recorded by the likes of Latvia, Lithuania, Bulgaria, Slovakia and Poland underscore wider concerns around judicial independence and the rule of law in several eastern EU member states.

Vigilance vital for avoiding hidden risks

Corruption can take on many forms, from low- to mid-level local officials demanding bribes for services through to leading politicians prioritising private interests over democratic integrity. But corruption of any kind can muddy political environments and stunt broader economic development.

Screening for risk is a crucial first step for any organisation looking to better understand its exposure to corrupt practices. Those that fail to do so are vulnerable to the financial, reputational and legal threats that inevitably come through association with corrupt individuals, businesses and governments.