A ‘Phase One’ trade deal announced in December 2019 does nothing to change the fact that we are in the dawn of a new era defined by strategic competition between the United States and China. This dynamic will likely serve as a significant source of geopolitical risk for companies and investors in the year ahead, as they are in danger of becoming pawns in a broader confrontation. Corporate entities will need to adapt their business strategies in order to navigate this evolving geopolitical landscape or risk becoming collateral damage.

The elevated levels of geopolitical risk that American firms operating in China, and Chinese firms operating in the US, have had to contend with amid the trade war represents the new normal rather than an anomaly.

In our view, the Phase One trade deal will only serve as a sticking plaster in a bilateral relationship that has an ever-growing number of pressure points.

We expect that strategic competition between the world’s two largest economies will steadily rise in 2020, in line with a long-term shift towards more adversarial bilateral relations and fuelled by the US presidential election.

The Trump administration will likely continue its systematic campaign to stymie the rise of Chinese tech companies, with an eye on the perceived threat they pose to America’s technological supremacy and national security. This approach will utilise criminal prosecutions, pressurising allies to bar Chinese telecoms firms Huawei and ZTE from participating in the rollout of 5G networks; and restricting the export of critical tech components to Chinese firms via the US Entity List.

Register for our Political Risk Outlook 2020 webinar

Conversely, US firms are particularly exposed to Beijing’s plan to establish its own ‘Unreliable Entity List’ of foreign individuals, businesses and organisations perceived to pose a threat to China’s national security or economic interests. US delivery firm FedEx has been identified by China’s state-owned media as a prime contender for inclusion on the list after it allegedly re-routed Huawei documents to America on the request of US law enforcement agencies. The case provides a cautionary tale of how corporates are no longer mere bystanders in the geopolitical power struggle.

The establishment of a Chinese blacklist would institutionalise Beijing’s currently ad hoc means for punishing foreign companies for their perceived transgressions and those of their home governments.

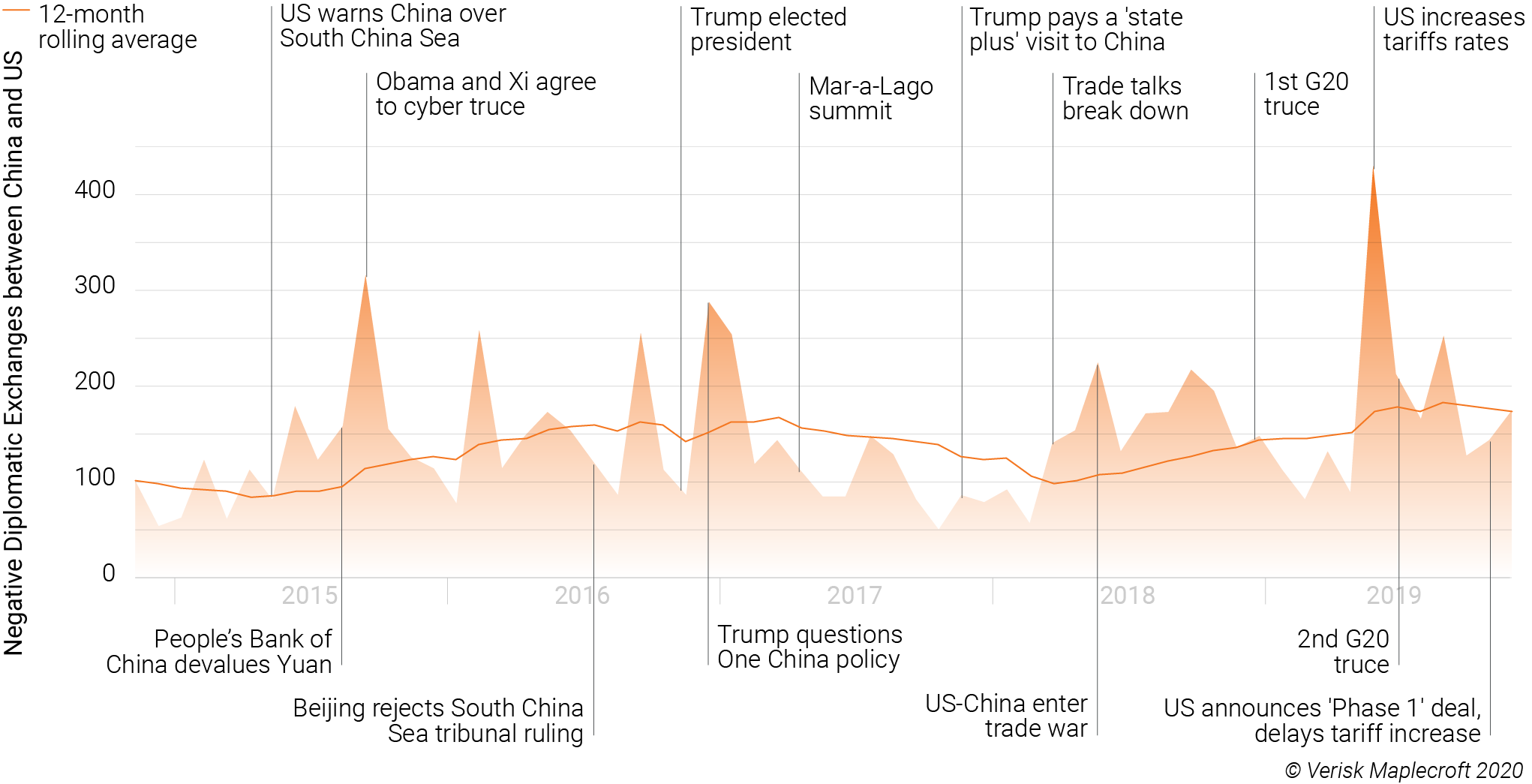

As illustrated in Figure 1, the trade war has been the most prominent source of friction in the US-China relationship since the start of 2018. Bilateral relations have been characterised by cycles of increased geopolitical tensions followed by de-escalation depending on the status of trade negotiations.

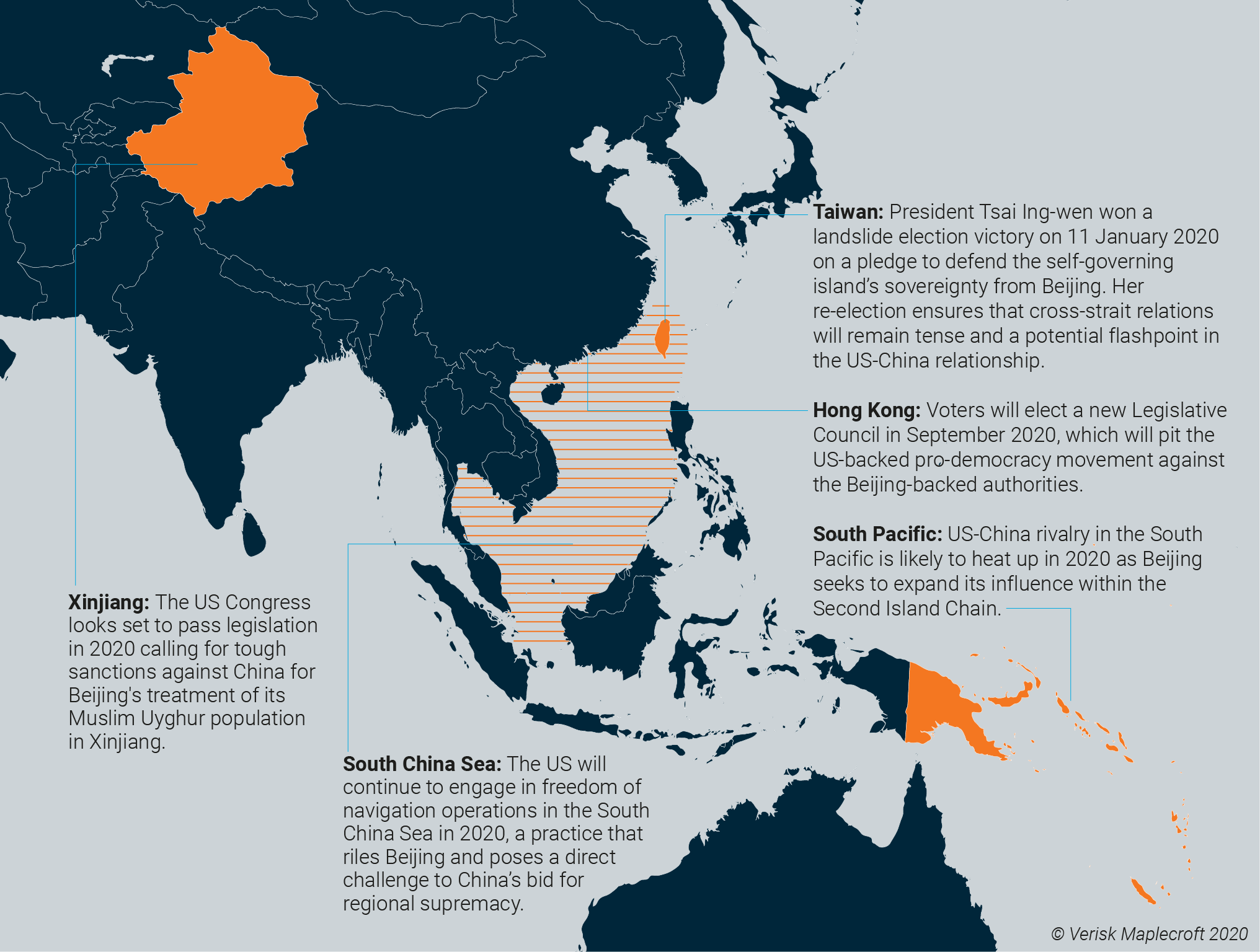

However, the trend of increasing strategic competition pre-dates the trade war, and indeed, the Trump presidency. The trend line in the chart shows that ‘verbal conflicts’ between China and the US – which we use as a proxy for geopolitical tensions – has become steadily more frequent over the past five years. Moreover, multiple pressure points exist in the US-China relationship beyond those economic issues covered by the Phase One trade deal (see Figure 2). All of this underpins our assertion that strategic competition between the US and China will likely escalate in 2020 and beyond, as will the associated geopolitical risks for corporates.

What is the market impact?

The market impact will be significant and varied. It will accelerate China’s push towards greater tech self-sufficiency − an objective best encapsulated in Beijing’s ‘Made in China 2025’ industrial policy to become a manufacturing superpower across 10 high-tech sectors, including robotics, semiconductors and green energy. This will entail narrowing opportunities for US firms across these sectors over the coming decade.

Greater strategic competition will also fuel the Trump administration’s bid to bolster ‘critical mineral’ supply security. Beijing’s threats to restrict the export of rare earth elements to the US has exposed the extent to which China’s dominant position across a host of mineral value chains poses a potential strategic vulnerability for Washington. Reducing American dependence on China will involve a combination of providing greater policy support for the mining sector at home and the building of ‘mineral alliances’ with resource-rich allies abroad.

More broadly, US companies with exposure to the mainland market will be prime targets during periods of heightened geopolitical tensions and may find themselves on the receiving end of China’s so-called ‘qualitative measures’, which include politicised regulatory probes, state-sponsored consumer backlashes and discriminatory import restrictions. International companies that are perceived to be siding with the US in this emerging ‘Great Power’ rivalry also risk earning Beijing ire and all the consequences that go with it.

Download the Political Risk Outlook 2020

What if... Trump loses the presidential election in 2020

One potentially important variable for the trajectory of US-China relations is whether Donald Trump wins re-election in the November 2020 presidential election, given that confronting Beijing has been a defining feature of his presidency. Our current thinking is that Trump has a 50-50 chance of winning a second term: US presidents seeking re-election have been successful in two-thirds of attempts in the post-war period, but Trump’s low approval rating and the fact that he is trailing in the polls in key electoral battlegrounds point to a tight race.

A victory for the Democrats in 2020 would not necessarily alter the fundamental trajectory of US-China relations though. None of the leading contenders for the Democratic nomination look likely to adopt a dovish stance against Beijing. In short, the shift towards increasing strategic competition between the US and China both pre-dates and will likely outlast the Trump presidency.