COP15: ‘Paris Agreement for Biodiversity’ hinges on finance

by Will Nichols and Dr Rory Clisby,

Hot on the heels of the COP27 summit, the much-delayed UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) summit, COP15, finally came to pass. Trailed as having the potential to produce a ‘Paris Agreement for nature,’ the meeting in Montreal lacked the global leaders of its climate counterpart, but arguably produced more concrete results, with commitments including:

- Protecting 30% of the planet’s land and seas by 2030 and starting the process of restoring 30% of degraded areas

- Reducing losses of high value biodiversity habitats to ‘near zero’

- Reforming USD500 billion of subsidies currently damaging nature

- Increasing requirements on business to report their risks from and dependencies on nature

- Creating a USD30 billion fund for biodiversity

While few countries met the previous CBD goals set in Aichi, Japan, there is growing recognition among world leaders that the global economy is highly dependent on functioning and healthy ecosystems. Around half of global GDP, some USD44 trillion, is thought to be generated by industries dependent on nature – and ever-closer links between efforts to combat climate change and damage to nature suggests that there is greater consensus and urgency around these goals.

The investment community is also beginning to factor impacts and dependencies on natural capital into decision-making. However, the lack of enforceability, dissension from African countries, and long-standing disputes over international funding threaten to undermine progress.

Here, we look at the key elements emerging from Montreal.

Protections for marine areas likely to lag behind those for land areas

Heading into the Conference, an agreement to legally protect 30% of both land and marine areas by 2030 had a wide base of support among developed countries. However, it was one of the most contested aspects of the talks and was only saved at the 11th hour. The new target builds significantly on the previous Aichi target of protecting 17% of terrestrial and inland waters and 10% of coastal and marine areas by 2020. In practice, protections for marine environments are likely to continue to lag behind, given marine impacts are far less visible and most of the worlds oceans fall outside national jurisdiction. With deep-sea mining emerging as a possible source to fill a projected deficit of much-needed energy transition materials, fragile and under-explored marine environments will face increasing pressures without much in the way of legal protection.

New horizons for nature-based financing

Public and private financing will be key to delivering the new targets. There is an estimated USD700 billion annual funding gap between what is currently spent on conserving and restoring biodiversity, and what is required to meet the COP15 targets. Developed countries have made clear they cannot provide all of these funds, and private capital and investors will be required to bridge the gap.

There is a compelling opportunity for sovereign debt investors to drive conservation improvements by tying finance to biodiversity-related milestones, such as expanding protected areas, particularly in countries which are economically dependent on potentially damaging commodity exports. Already we’ve seen investor groups link Brazil’s creditworthiness with positive deforestation outcomes.

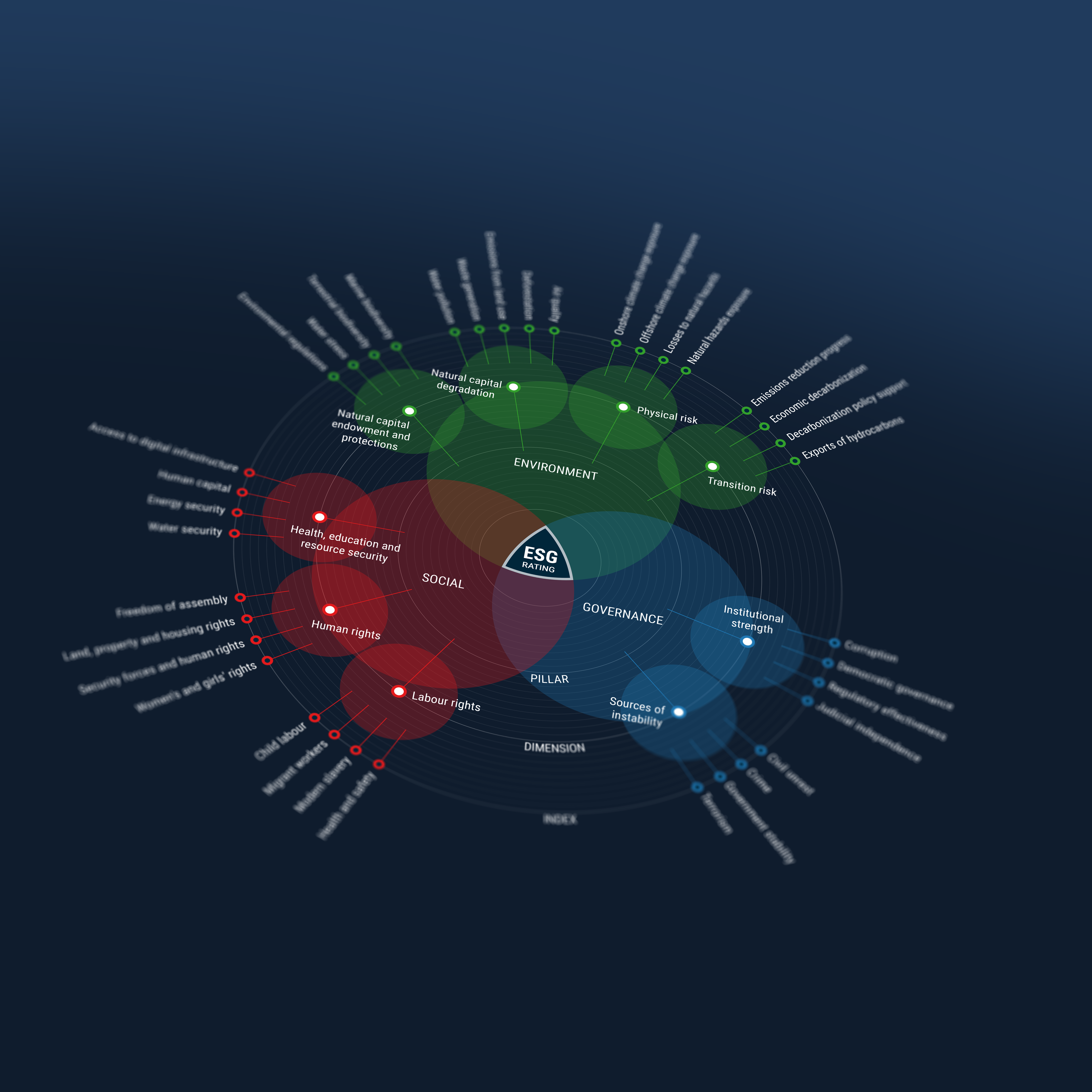

The figure below highlights the 118 countries with nature-based solutions in their Paris Agreement pledges, alongside the current coverage of terrestrial and marine protected areas and their performance in the Natural Capital Degradation dimension of our Sovereign ESG Ratings.

Ongoing debt pressures in biodiverse countries suffering extreme natural capital degradation, such as Madagascar, DR Congo, and Mozambique, offer potential opportunities for investor engagement around nature-positive policies and projects. Moreover, potential degradation in countries such as Papua New Guinea, where biodiversity is currently under lower pressure, can be avoided by support in the expansion of protected areas.

TNFD at forefront of greater reporting requirements on business

The wording of a commitment to ensure companies monitor and disclose their impacts and dependencies on business is deliberately equivocal to allow countries to go at their own pace. But there is potential for natural capital reporting to become a mandatory requirement in parts of Europe, North America and Asia-Pacific where some aspects of this are already in place.

Supercharging this is the rise of the TNFD which, by providing a standardised disclosure benchmark, allows regulators and investors to incorporate natural capital impacts and dependencies into risk management and strategic decision-making.

Can Montreal learn lessons from Aichi and Paris?

The 2020 biodiversity targets were ambiguous and complex, with progress difficult to measure due to poor data availability. The COP15 agreement will seek to address this. It will implement a monitoring framework and require governments to integrate targets into national law and policies. They will also have to report on progress through national biodiversity plans – mirroring the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement.

Perhaps more critically, much of the world’s richest biodiversity is found in middle- and low-income countries where greater support to protect and enhance natural capital is required. The establishment of sustainable funding flows such as green and blue bonds, which place a focus on protecting and enhardening biodiversity, will be critical to meeting the goals set at COP15. Both governments and private investors will have a vital role.