China’s social credit system raises risks for corporates

by Sofia Nazalya,

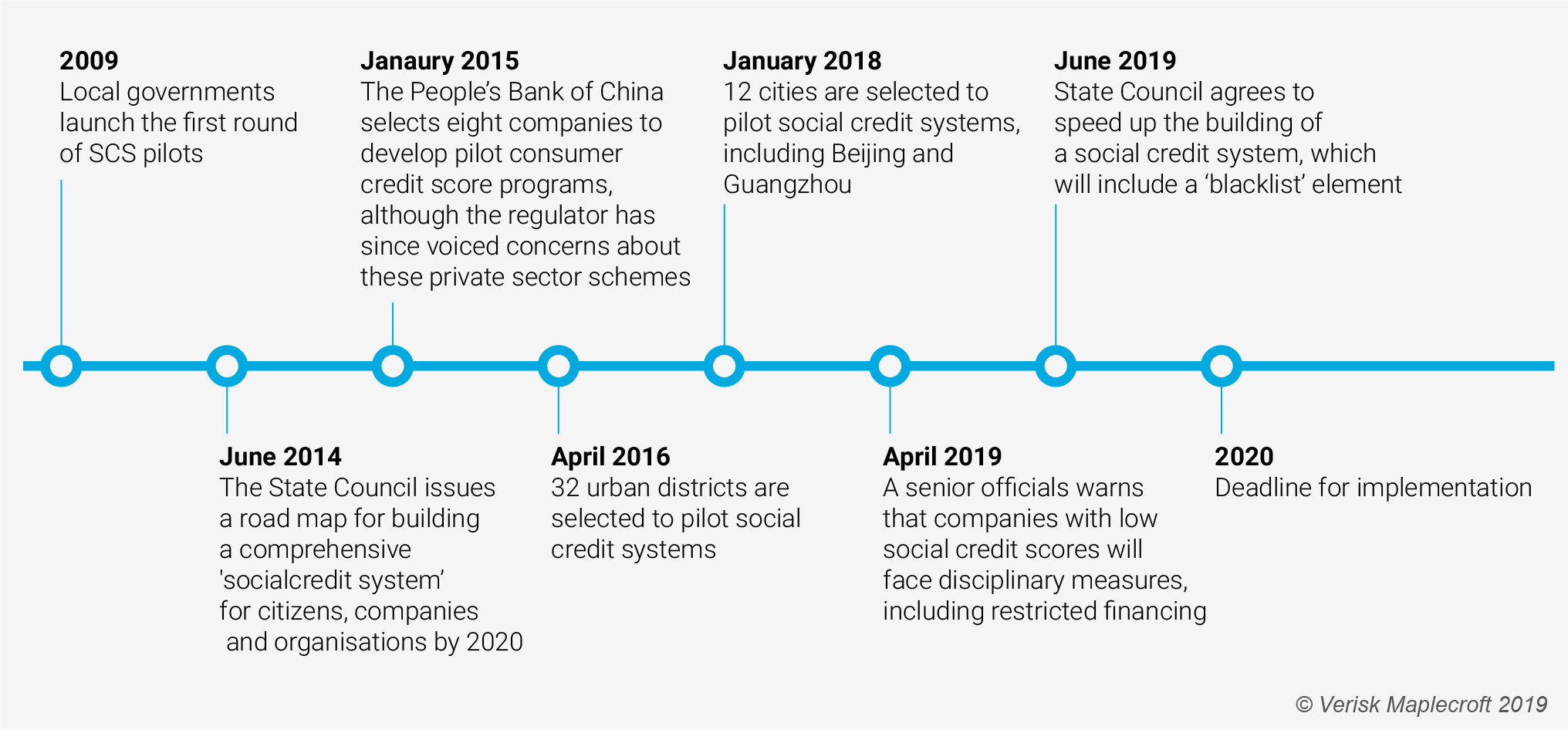

China is in the midst of developing a nationwide social credit system (SCS), which aims to harness the power of Big Data, high-tech survellience and artificial intelligence to track and shape the behaviour of its citizens and businesses. The broad idea is to reward ‘good’ behaviour and punish ‘bad’. Needless to say, it will be the Chinese Communist Party that serves as the sole moral arbiter of this gargantuan exercise in social engineering.

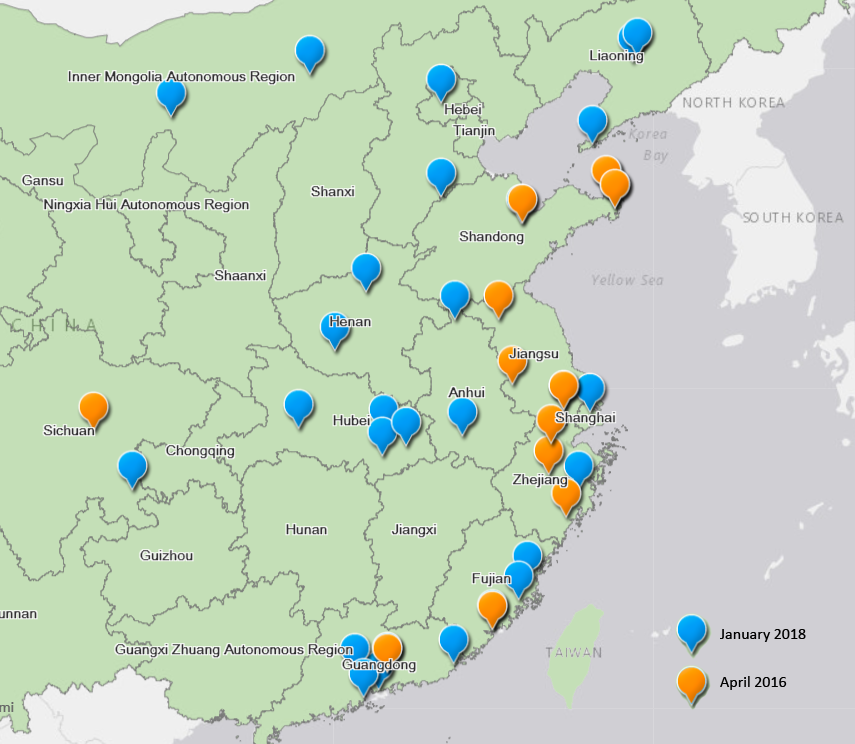

What the system will look like when fully up and running remains unclear, as an assortement of existing official pilot schemes and private sector initiatives currently take on a variety of forms. However, the government aims to have a unifed social credit system in place in at least Tier 1 and 2 cities by 2020. Once implemented, this system is likely to play a key role in influencing Chinese citizens’ ability to do a host of activites, from accessing public services and getting a job to starting a business or taking out a loan. Moreover, all companies registered in China will be allocated social credit codes, which the authorities will use to monitor and record their activities. Under the current proposals, strict penalties will be meted out to entities that act in ‘bad faith’, including denying them access to the world’s second largest economy.

Social credit system raises reputational risks for companies

Beijing’s dire human rights record suggests that a social credit system is likely to be used for illiberal ends, such as silencing political dissent. Indeed, civil society groups are already pointing to examples of the authorities using the pilot schemes up and running as a means to target those critical of the state.

What exact data will be captured and collated within the national scheme remains unclear, but plausible inputs include social media activites, personal networks, consumer spending habits and financial history, alongside records held by the central government, local authorities and security services. More nefarious would be the inclusion of people’s movements captured through advanced facial recognition software, such as that in use to monitor the ethnic Uighur population in Xinjiang. Companies operating in China would face reputational risks if they are either legally required to provide personal employee data to the authorities or come under pressure to do so.

Register for our Human Rights webinar to find out more

Companies with bad social credit score risk losing access to the Chinese market

The Chinese government does not, however, see the SCS merely as a way to monitor citizens, but also as an effective tool to ‘direct and regulate’ the market. Under the social credit system, the acitivities of companies would be monitored, tracked and strict penalities handed out to those with poor scores. These look set to include sanctions such as restrictions on stock issuances, increased inspections and even lose of market access.

The danger for foreign firms is that the system would effectively institutionalise Beijing’s habit of punishing foreign coporates for perceived slights – either resulting from their own activies or the conduct of their home governments. There have been multiple recent examples of foreign companies that have fallen afoul of Beijing being punished through plausibly deniable means, such as state-stoked consumer backlashes or an uptick in non-tarrif barriers. However, there have also been examples of Beijing explicitly threatening companies to force them to comply with its edicts or face the consequences. The most notorious example to date is a demand in May 2018 that foreign airlines refer to self-governing Taiwan as Chinese terrority or risk closer ‘admistrative scrutiny and demerits on their social credit records’. All 36 carriers who received the threat eventually complied and the incident perhaps provides a taste of things to come.

A coersive tool to keep foreign companies in line?

There is a credible threat that China’s nationwide social credit system will evolve into a coersive tool for Beijing to keep foreign companies in line. Once it is fully implemented, companies risk being stuck between a rock and a hard place. Non-compliance could cost them access to the world’s second largest economy. While there are currently many uncertainities surrounding its final form, the social credit system may leave foreign companies with difficult decisions and little room to manoeuvre.