China's pragmatic Myanmar policy under fire

by Dr Kaho Yu,

Weeks of demonstrations and a deadly crackdown have roiled Myanmar since 1 February 2021, when a coup returned the country to full military rule. China, a neighbour and major investor in Myanmar, has been taking a silent approach towards the coup, but has not been able to avoid entangling its investments in the crisis. On 14 March, Chinese garment factories in the Hlaing Tharyar district of Yangon were looted and destroyed during anti-military protests. In response, Beijing urged the military government to do more to protect its extensive business investments in Myanmar, including factories, pipelines and other big infrastructure projects. China’s frustration with the risks facing its economic interests indicates that the coup has become a major test for the already complex Myanmar-China relationship.

Investment plays a key role in Myanmar-China relations

Beijing has historically cultivated cordial relations with both the military hierarchy and Aung San Suu Kyi’s civil government. Due to the Rohingya crisis, international pressure has pushed Myanmar further towards China, which has shielded Myanmar from UN sanctions with its veto power.

Learn more about our Country risk intelligence

China has been ambitious in expanding its Belt and Road (BRI) footprint in Myanmar. This ambition is exemplified by the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) signed in 2017. Despite delays in project implementation, the CMEC aims to promote a number of infrastructure projects that strategically connect the oil trade from the Indian Ocean to China’s Yunnan province via Myanmar.

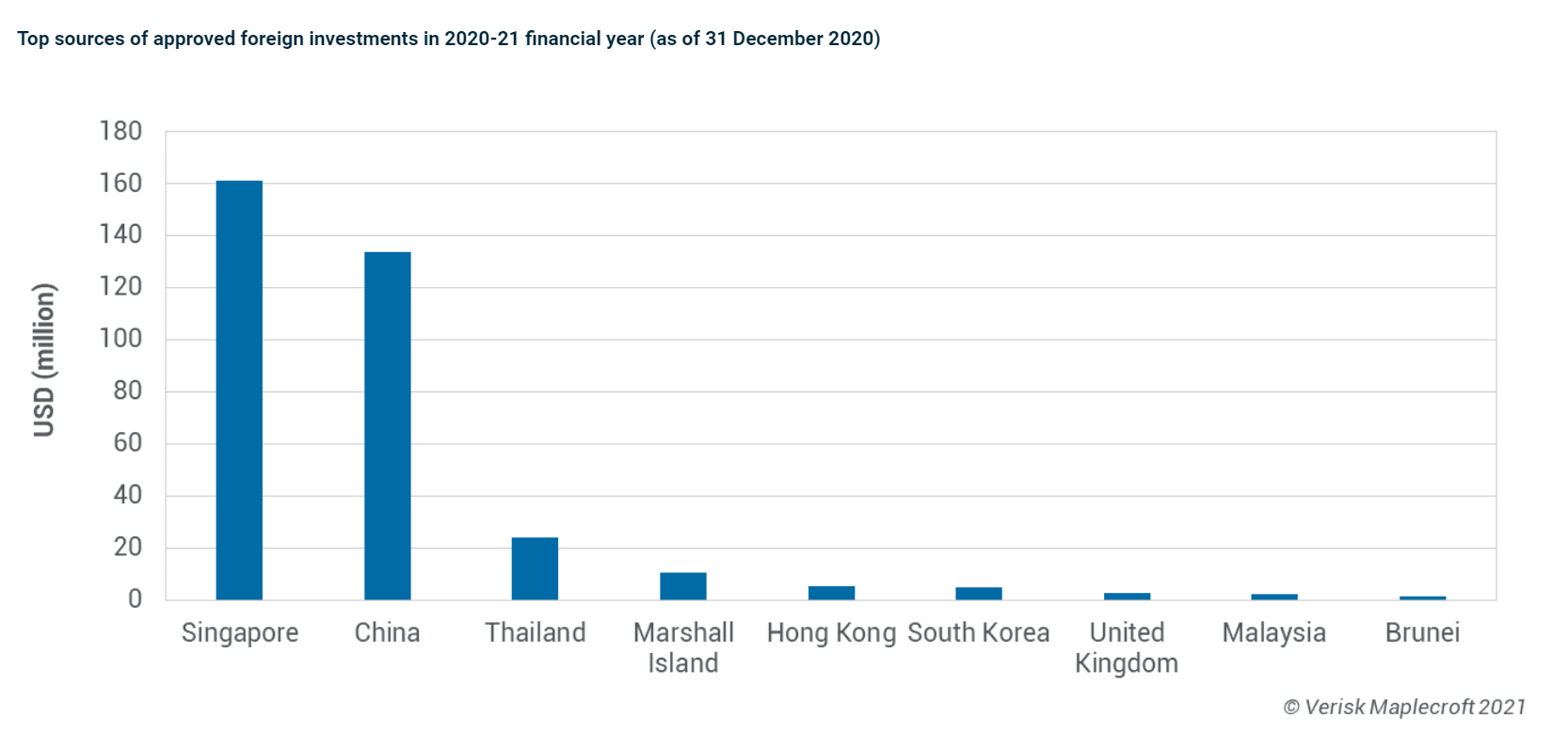

In 2020, which marked the 70th anniversary of China-Myanmar diplomatic relations, both sides signed another 33 bilateral agreements, intended to facilitate the CMEC, during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s state visit in January. In spite of the business disruption brought about by the COVID-19 crisis, China has continued to urge the Myanmar government to speed up the implementation of planned CMEC projects, including the Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone and the New Yangon City project. Indeed, China remained the second-biggest investor in Myanmar in its 2020-21 financial year, after Singapore and far head of any other country(see visual below), reflecting its economic influence in the country. In general, Beijing expects investment in Myanmar to contribute to its energy security, trade and stability in its neighbourhood. China maintains that an economic slowdown in its neighbourhood would result in social instability and security threats, which would in turn threaten the political stability of Chinese border provinces such as Yunnan.

Four signals to watch in post-coup Myanmar-China relationship

China has taken a ‘wait and see’ stance towards the coup, emphasising that its priority is stability and that local politics is Myanmar's internal affair. For Beijing, it does not matter who rules Myanmar, as long as those in power are not anti-China. Beijing’s request for the protection of its citizens and assets after the March factory attacks suggests that it has accepted the military government as the new leadership. While Beijing is hoping to find a reliable partner when the dust settles, we have identified four signals that corporates and investors should pay close attention to in order to gauge the course of the Myanmar-China relationship over the next 1-2 years.

1) Beijing’s economic interests at stake: Although China has not hidden its support for an authoritarian government in Myanmar, it tends to prioritise stability above all else. The 2021 Myanmar coup has placed Chinese projects directly at risk and threatens Beijing’s economic interests in the country. While Chinese companies in Myanmar are reportedly pulling out non-essential staff, it remains unclear if the military government will honour or re-negotiate the Chinese projects and agreements previously approved by Suu Kyi’s administration.

2) Growing anti-China sentiment: The Myanmar public has long been wary of controversial Chinese engagement in Myanmar, from predatory resource extraction to ethnic minority issues and surveillance tech exports. The ongoing civil unrest fuelled by social media is further worsening the fear of China’s rise in the region. The growing anti-China sentiment will likely become a flashpoint in the Myanmar-China relationship as a result. For example, the recent factory attacks have further placed Chinese investment in the centre of the domestic political dispute, straining Beijing’s relationship with the military government.

Learn more about our risk indices

3) Myanmar’s attempt to reduce Chinese influence: The military government is also aware of growing Chinese influence in the country. There are reports indicating that the junta has sent third party lobbyists to repair its relationship with the West as a way to distance itself from China. Indeed, the Suu Kyi government was also wary of becoming too dependent on China and tried to neutralise Chinese influence by reaching out to India for strategic cooperation and scrutinising inward Chinese investment. We expect Myanmar to continue to be cautious with Chinese megaproject investments in an effort to avoid financial overreliance.

4) Changing geopolitics: The promise of more counter-measures from the West against the coup, such as sanctions, would drive Myanmar even closer to China. Russia, which is Myanmar’s major weapons supplier, is also showing support for the country’s new military leadership. While China and Russia will continue to shield Myanmar from UN sanctions, the military government is also wary of depending too much on them. We also expect South East Asia to become more of a priority for the Biden White House than it was for the Trump administration. The US’ increasing security cooperation with the sub-region will likely present a small window of opportunity for Myanmar to avoid aligning too closely with China and Russia.

Political instability remains a major risk in bilateral relations

While political instability has led to business disruption, Myanmar will remain a long-term destination for Chinese investment, particularly in the energy, mining and infrastructure sectors. Once the political turmoil settles down, we expect China to resume efforts to integrate Myanmar into its economic orbit.

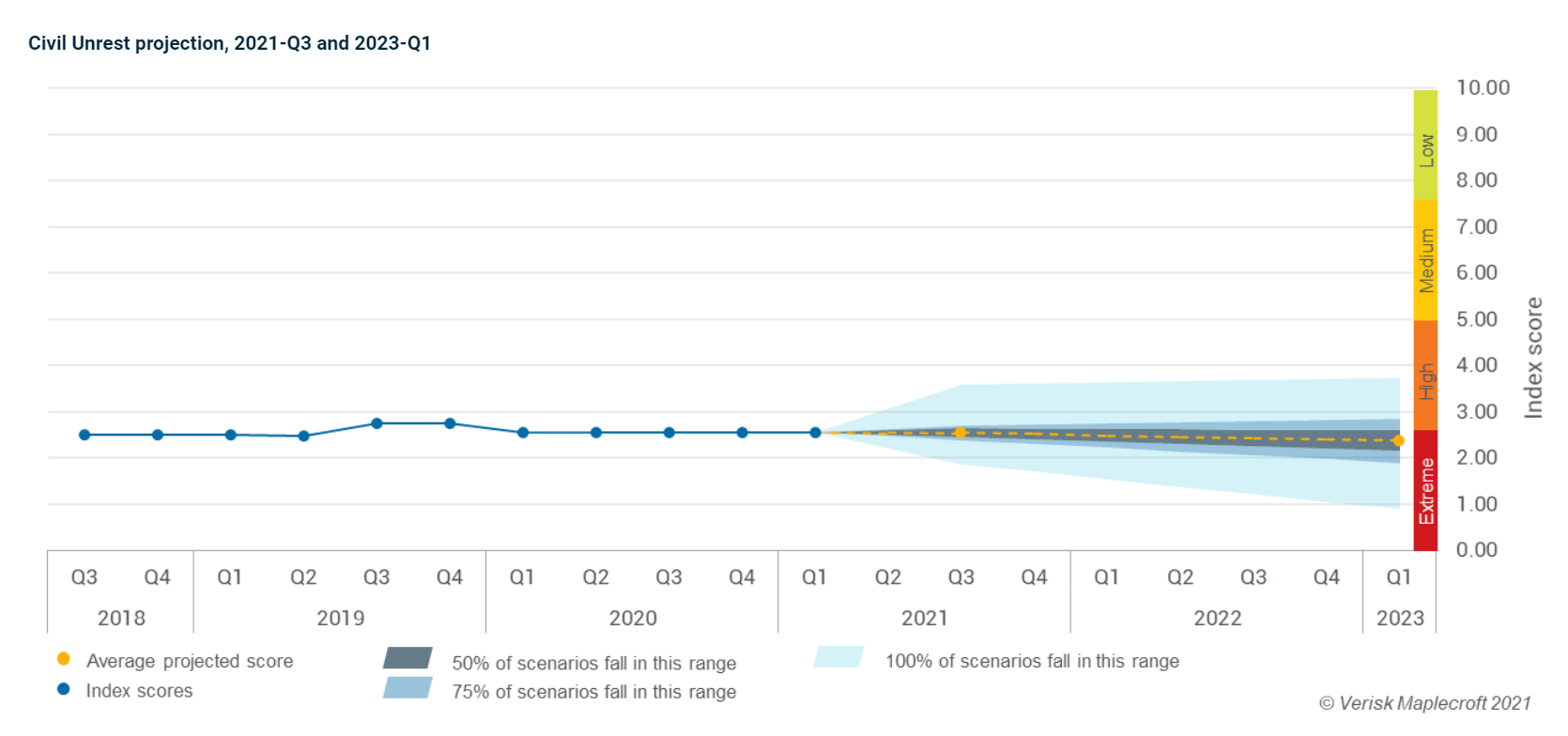

However, the deadly crackdown on protests in Myanmar will continue to fuel uncertainty and disputes in Sino-Myanmar relations. The military’s increasingly repressive tactics to hold on to power are unlikely to see the end of civil unrest. According to our pre-coup Civil Unrest projection, Myanmar was already set to remain in the extreme risk category for the next two years (see figure below), and we expect future updates to reflect the post-coup escalation in unrest.