Brussels asserts “strategic autonomy” with EU-China investment deal

by Franca Wolf,

The EU took one step closer to sealing a key aim of 'strategic autonomy' when it and China reached a preliminary agreement on a key investment deal on December 30. The EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) falls short of the “fundamental rebalancing” that the EU sought with the world's second largest economy, but European companies will benefit from expanded market access in China. On top of that, the agreement demonstrates the EU's resolve to strengthen its geopolitical hand and place itself on a more equal footing with the US ahead of a Biden presidency despite concerns over China's human rights record.

Balancing the US and China for strategic autonomy

We previously identified the CAI as a signpost for EU-China relations and argued that the gradual progression of negotiations would confirm our base scenario of stability in EU-China ties in the aftermath of the pandemic. In some ways, the CAI presents a further institutionalisation of economic ties. However, the long duration of negotiations (which started in 2013) and the fact that it falls far short of a free trade deal, highlights persisting limits to deeper trade liberalisation.

Moreover, we do not consider the CAI to come at the expense of EU-US relations. The conclusion of negotiations followed a last-minute comment by the incoming Biden administration suggesting that the EU delay the end of negotiations until the official start of Biden’s term, so that they can coordinate their approach to Beijing. The media have framed the EU’s decision to conclude CAI negotiations as a rebuke to Biden, straining the projected rapprochement between Brussels and Washington under the Democratic President. However, in reality, Brussels’ decision to conclude CAI negotiations highlights the EU’s determination to continue with its “balancing” approach vis-à-vis China and the US, seeking to prevent excessive dependence on either side.

Find out more about our Country Risk Intelligence

The at times antagonistic transatlantic relations under President Trump pushed Brussels’ aim of “strategic autonomy” up on the agenda. Although we expect US-EU relations to improve under Biden, the progress on CAI suggests that the EU will seek to establish itself as a global leader on equal footing with the US. Indeed, rather than undermining a united US-EU strategy on China, the CAI arguably strengthens their negotiating position. If ratified, the CAI would afford the EU similar rights to the US-China Phase One agreement for the US. A more equal starting point likely decreases the risk that Beijing will seek to play the US and EU against each other.

Better market access but ESG risks loom large

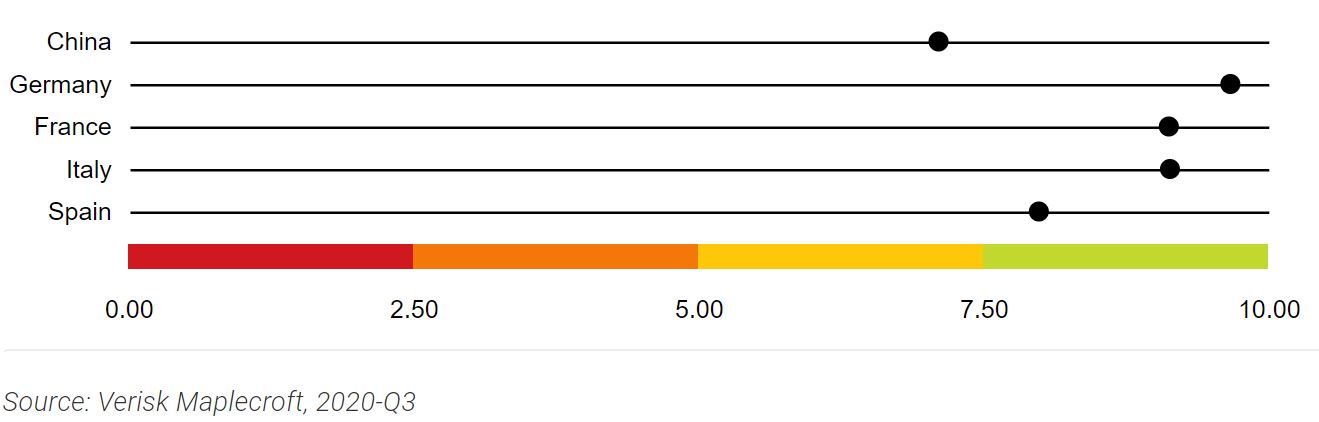

The CAI will improve market access for European business in China. Our Barriers to Entry Index, which assesses the ease of establishing business operations in any given country, highlights how major EU markets score well above China reflecting existing asymmetries (see figure below). European business lobbies like the European Chamber of Commerce in China have welcomed the conclusion of CAI negotiations.

However, the deal also risks EU businesses becoming more exposed to ESG issues. This is because although the Commission has hailed the agreement’s explicit reference to ESG issues as a major success, the protection of ESG standards will be difficult in practice. The CAI requires both sides to adhere to the Paris Agreement and labour rights, namely requiring Beijing to “make continued and sustained efforts” to pursue the ratification of two fundamental International Labour Organisation norms. However, the lack of concrete commitments on a timeline for ratification demonstrates the limits of the EU’s commitment and ability to upholding ESG standards outside the bloc.

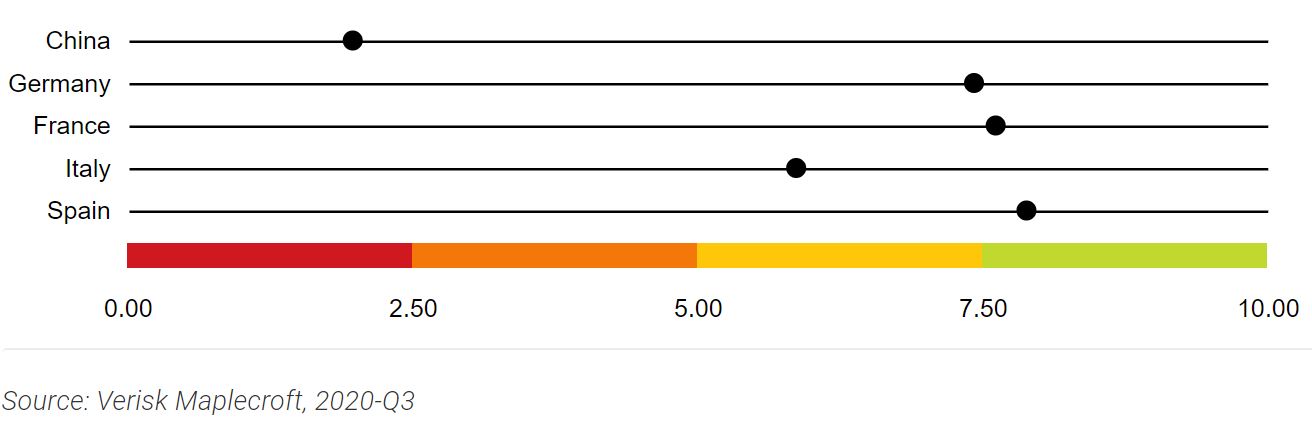

Increased market access also means European businesses will become more exposed to human rights violations in their Chinese supply chains. China is in the extreme-risk category in our Modern Slavery Index, which measures the risk to business of the possible association with slavery, trafficking in persons and forced labour in supply chains, operations and service providers. Even if China was to strengthen its legal framework, the severity and frequency of violations means the risk of labour rights violations will remain in practice (see figure below).

Outlook

The CAI still needs to undergo several steps before entering into force. Brussels and Beijing will now finalise the text, followed by months of legal scrubbing and translating. The European Parliament and 27 national governments will then need to ratify the deal. This process will likely not be completed until the first half of 2022.

The EU Parliament is generally more progressive on ESG issues than national governments, and several prominent MEPs have already signalled that they will fight for more stringent labour standards and human rights when it comes to ratification. Nevertheless, there will likely be a majority to ratify the deal in the Parliament.