Biodiversity risk is the new ESG elephant in the room

Environmental Risk Outlook 2021

by Will Nichols and Dr Rory Clisby,

Just as companies are getting used to the idea of having to report their climate change risks, investors are demanding they now cover a whole new spectrum of issues related to corporate environmental performance. Water, forests and increasingly biodiversity are shooting up the agenda as links between so-called natural capital risks and the impacts of companies become clearer.

This year marks the beginning of the Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), which aims to create a standardised way of measuring threats to wildlife and ecosystems. In time, this will unleash a wave of calls from the investment community for corporates to account for biodiversity risk, especially across assets such as mines, oil operations and pipelines. What’s more, if world leaders are able to secure a Paris-style worldwide biodiversity deal in China later this year, it would drive momentum for the introduction of hard regulations addressing biodiversity risk.

us$2.6tn

Estimated figure of loans and underwriting services provided by the world’s largest investment banks linked to the ‘destruction of nature’ in 2019

In the same way as carbon restrictions threaten emissions-heavy investments, so more stringent biodiversity laws will affect activities impacting nature. One estimate suggests the world’s largest investment banks provided around USD2.6 trillion (GBP1.9 trillion) of loans and underwriting services linked to the ‘destruction of nature’ in 2019. With huge sums under threat and pressure from legislators and civil society growing, investors – and operators – need to find a way to manage this risk.

Biodiversity hotspots under attack

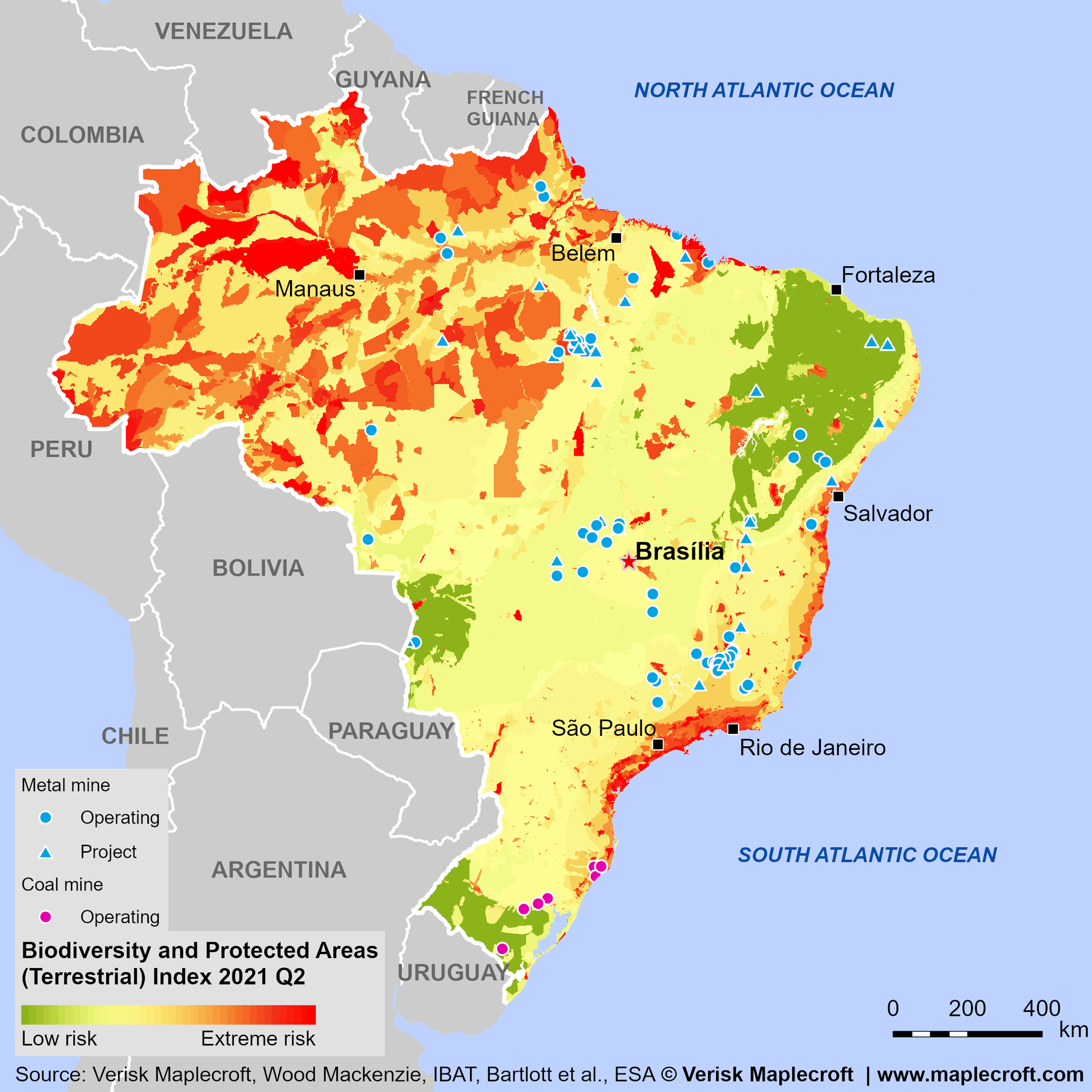

Biodiversity risk is a factor of both the presence of valued ecosystems and species, as well as a country’s intent and capacity to protect them. One obvious example to focus on is Brazil, where mining operations have faced protests from adjacent communities and NGOs over their impact on biodiversity-rich areas. The map below shows extensive biodiverse areas adjacent to mining operations; Bolsonaro’s disregard for Amazon protections further highlights the importance of extensive due diligence for companies operating in or sourcing from the area.

The idea of ‘natural capital’ – effectively putting a price on nature by factoring ecosystems into measures of financial performance – is not without controversy, but proponents argue that failing to value biodiversity effectively is a key driver in accelerating rates of loss. Without a dollar value to consider, companies can make short-term decisions that fail to account for the harms that large-scale investments in sectors such as agri-business or extractives can reap. And the economic prospects of razing rainforests to expand a mine will look less impressive if the operator’s social licence to operate also goes up in smoke.

TNFDs among key steps to cultivate a global framework

But measuring these risks requires universal benchmarks. The forthcoming TNFD recommendations will be a key component in standardising measurement of biodiversity risk and encouraging companies to embed natural capital risk into decision-making and strategies. We expect biodiversity disclosures to follow the same pattern as climate risk, where investors are put under pressure to publish information so that, in turn, they demand more granular and material data from their portfolio companies.

Calls to expand the EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities, to include definitions of which projects are beneficial and detrimental to natural capital, will not escape the notice of investors or operators given such a move could make raising finance for those projects much more difficult. Another consideration is the Finance for Biodiversity (F4B) initiative’s suggestion that financial institutions become legally liable for their impact on ecosystems.

Regulatory support for TNFDs could come at the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) meeting in China in October, postponed from autumn 2020. Parties will discuss a new roadmap and targets to protect biodiversity for the coming decade, aiming to produce a Paris Agreement-style treaty for collaboration on natural capital risk. However, major hurdles to overcome include the US remaining outside the CBD and the fact that the pandemic has pushed economic priorities above natural capital protections for many nations.

ESG activism branches out

Funds and international creditors have an opportunity to drive conservation improvements by tying finance to ESG milestones. Ongoing debt issues in countries such as Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Angola and Zambia offer potential opportunities for engagement, as well as a number of other countries highlighted in the graphic above.

Those countries furthest away from the 2020 Aichi Biodiversity goal of protecting at least 17% of terrestrial areas and inland waters could find themselves targeted by sovereign ESG investors, while operators in those nations must be aware of the potential for safeguarded areas to expand. Investor attempts to sway Brazil’s Bolsonaro administration, which emphasises economic development above environmental protections, have gained access to senior policy-makers, but failed to rein in destruction of the Amazon. However, governments could soften their positions if access to finance were to become a problem.

Corruption intensifies threats to biodiversity

Direct investments in countries will also play a crucial role in addressing natural capital risk. Innovative private funds looking to catalyse investment into the world’s stocks of natural assets already attract support from sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and insurers, particularly for investments in emerging markets.

However, the lack of accurate and granular data not only hinders reporting, but masks poor governance. Corruption and misrule provide the cover for natural capital value chains – such as timber or livestock, or crops like soy and palm oil – to destroy nature largely unimpeded and potentially out of sight of certification agencies.

The graphic below highlights emerging and frontier markets where biodiversity is at risk and corruption is widespread. Brazil, Indonesia and Malaysia – all major exporters of agricultural commodities – clearly pose significant risks for investors, alongside Peru, whose economy hinges on mining, and Mexico, where AMLO is stepping up oil and gas expansion. Among developed markets, only Italy can be considered similarly risky.

Biodiversity risk blossoms

The financial sector, alongside real asset operators dependent on its capital, need to put resources towards tracking, measuring and managing biodiversity risk. The lesson from climate risk reporting is that certain existing processes can be repeated, but a new way of thinking needs to be embedded from the top down to truly realise the benefits.

And the benefits of getting the process right are substantial: identifying and mitigating biodiversity impacts helps investors and corporates anticipate regulatory shifts and shield themselves from reputational and litigation risks. And, just as with climate risks, there is an opportunity to make smarter investments that tap into the potential of preserving and enhancing ecosystems and natural capital services.