Australia trade figures hit by geopolitical tensions with China

by Joseph Parkes,

Australian trade data released on 25 March– which shows that export values from key sectors in 2020 were markedly down on those from previous years – reveals the impact of Beijing’s restrictions on Australian exports.

While there has been a slowdown in exports across the board as a direct result of COVID-19’s impact on the global economy, the downturn in exports to China was considerably higher (with the important exception of iron ore), indicating the role that geopolitical tensions between the two countries are playing in Australia’s trade performance. And there is no sign of improvement to come.

Indeed, the trade results have been released against a backdrop of soaring geopolitical tension. On 22 March, Australia’s parliament debated a motion on rights abuses in Xinjiang, which prompted Chinese foreign ministry officials to call for Australia to face war crimes investigations over the conduct of its soldiers in Afghanistan. Relations between Beijing and Canberra have soured over the last two years, driven both by bilateral issues and by the fact that Australia is a close ally of the US.

Australia struggling to find alternative markets for some banned commodities

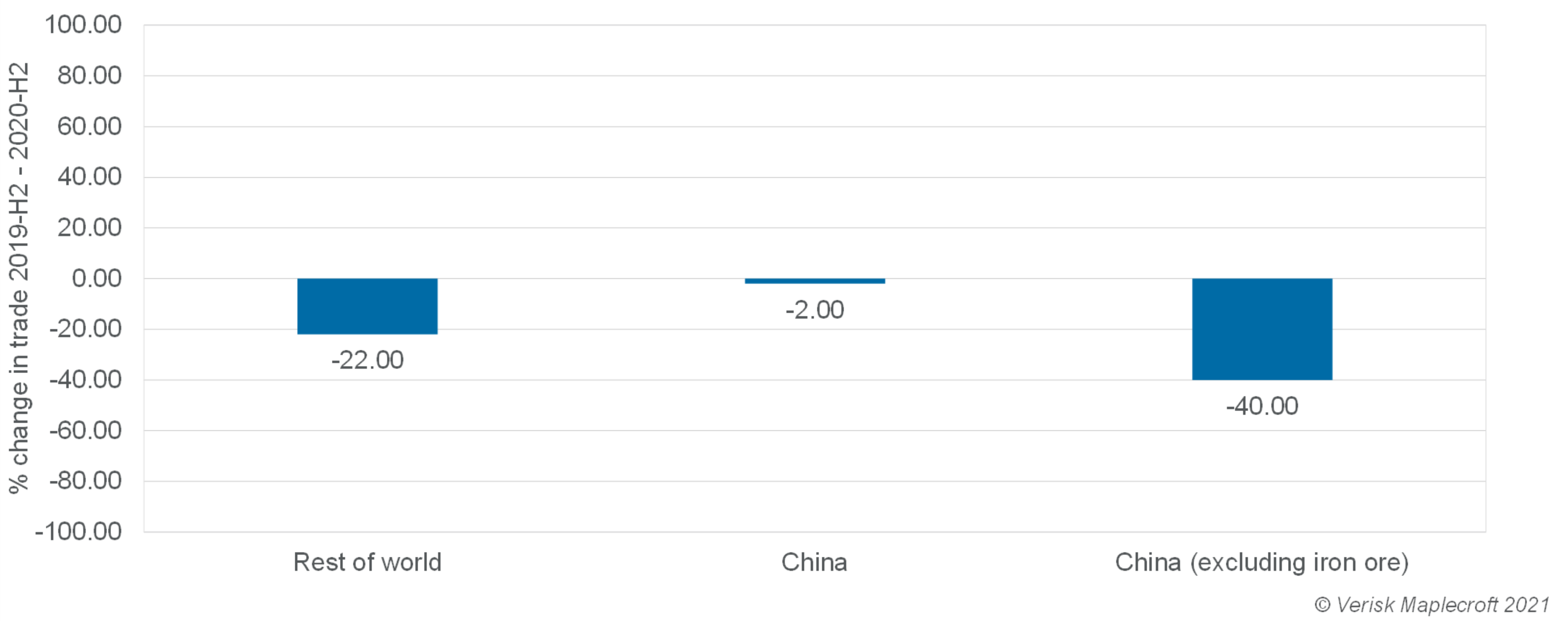

The trade figures presented in the Australian Senate confirm that Beijing’s sweeping trade restrictions have proved highly effective in curtailing bilateral commodity trade in targeted sectors. Exports to China fell by around 40% in value in the second half of 2020 compared with a year earlier, once iron ore is excluded, while exports to the rest of the world dropped by 22%.

The current round of import restrictions imposed by Beijing began with a ban on Australian coal imports in October 2020. Since then, China has moved to curtail imports of an array of Australian commodities, including barley, wheat, lobsters, wine, beef and timber. On 26 March 2021, Beijing confirmed that its tariffs on Australian wine will stand for the next five years, formalising curbs on the wine sector that were imposed earlier this year.

Australian Trade Minister Dan Tehan described the move as “extremely disappointing and completely unjustifiable”.

However, the overall impact on the targeted sectors is uneven, a key factor being the ability to find alternative markets. For example, Australia’s coal, barley and cotton exports have remained relatively strong overall, with sellers able to redirect exports to alternative markets such as India, albeit often at lower prices. However, the impact on wine and lobster exports has been more significant, causing severe disruption in areas where these industries are based – triggering calls for government support.

Iron ore the one economic bright spot, with risks attached

The depressing picture for some commodities in the trade data is balanced by iron ore’s record performance, with booming export volumes and prices propping up the headline figures thanks largely to a supply crunch in key rival exporter Brazil. Iron ore has so far remained immune to trade friction with Beijing since Australian imports have an irreplaceable role as a feedstock to China’s steel industry.

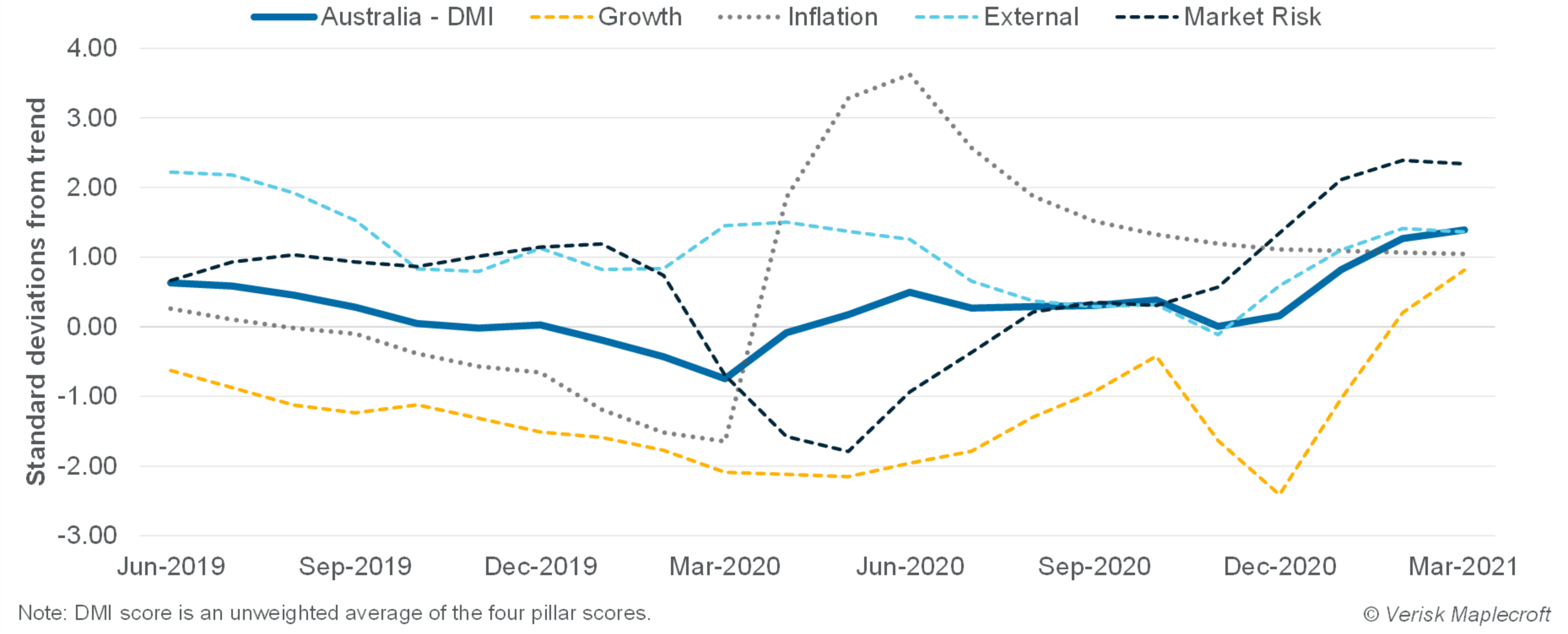

In fact, the strong performance of iron ore prices and exports has more than tempered the overall economic impact of Beijing’s trade restrictions, and continues to underpin Australia’s relatively rosy economic outlook. Our Dynamic Macroeconomic Index shows Australia’s key macroeconomic indicators moving robustly back into positive territory (see visual below), and we expect the economy to grow by more than 4% in 2021, an impressive rebound given that Australia also experienced a less severe slump than most other countries in 2020.

However, the increased reliance on iron ore carries risks – particularly with prices likely to moderate from their recent record levels over the next year, according to our sister company Wood Mackenzie. A deeper than expected dip in iron ore prices (which could be triggered by factors such as a rapid increase in the use of scrap metal in Chinese steel) would quickly change the outlook for government finances.

What does the future hold?

A number of recent developments strengthen our view that there is only a remote chance that 2021 will prove to be a less tumultuous year for Australia’s China exports. Beijing’s move to formalise its punishingly high tariffs on Australian wine is the first of these, likely setting the scene for another WTO dispute.

Secondly, on 18 March 2021, the first face-to-face meeting between senior officials from the US and China since President Biden took office was marked by a combative tone, and little suggestion of progress on the key issues souring the bilateral relationship. The meeting effectively ends any remaining hopes that the Biden transition would see a smooth rapprochement between Beijing and Washington and its allies.

Thirdly, Canberra shows no appetite for folding on key issues causing friction. In fact, we think it likely that the government will adopt a Magnitsky-style law later this year, which would allow the application of targeted sanctions against perpetrators of serious human rights abuses. Any such moves will prompt a further deterioration in the relationship with Beijing.

Likewise, Canberra’s continued enthusiasm for participation in the ‘Quad’ – an informal strategic grouping of Australia, US, India and Japan – following the first ever meeting of the participating countries’ leaders on 12 March 2021, will also be an ongoing bone of contention with Beijing.

The steady tempo of these fresh diplomatic clashes underpins our assessment that trade friction with China will continue this year, despite the fact that iron ore remains protected from significant disruption due to its irreplaceable role in the Chinese economy.