Aukus commits Australia to geopolitical competition

by Joseph Parkes,

On 15 September, the creation of a far-reaching new Australia-United Kingdom-United States security partnership, known as Aukus, was announced. The pact, which will advance the sharing of military technological capabilities in frontier areas such as AI, quantum computing and hypersonic weapons, marks a big shift in Australian military capabilities, albeit one which will likely take a decade or more to materialise.

The first order of business is a big one: to support the acquisition by Australia of eight nuclear-powered (though not nuclear-armed) submarines or SSNs, making use of extremely sensitive defence technology developed by the US and UK.

There had been little doubt as to where Canberra stood in the geopolitical competition between Beijing and Washington, but this announcement unequivocally and materially ties Australia to the US and UK for the long term. Prime Minister Scott Morrison described the new trilateral relationship as a “forever partnership”, and Australia is now committed to Australian and British technology, support and expertise over the multi-decade lifecycle of the next generation submarines. Australia is also set to buy US developed Tomahawk land attack missiles and longer-range Joint Air-to-Surface Stand-off missiles over the coming years.

A boost to US pushback against China

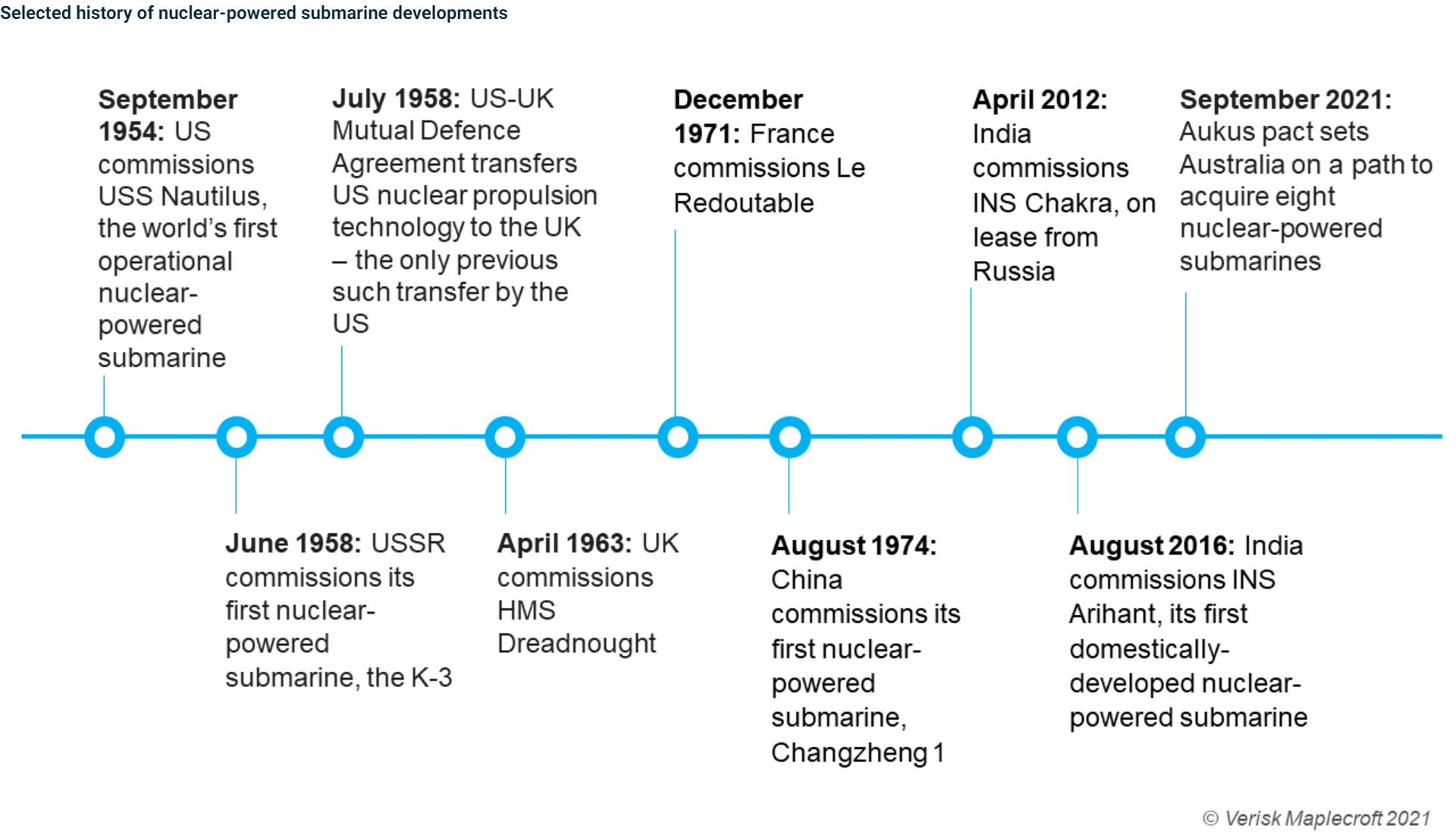

The submarine deal spells the end of Canberra’s troubled, AUD90-billion (USD65.6-billion) deal to acquire diesel-electric submarines from French company, Naval Group, and will see Australia become the seventh country to build SSNs (see timeline). But Canberra will pay a hefty financial, and diplomatic, penalty with Paris for terminating the contract. Paris has already taken the unprecedented step of recalling its ambassadors to Australia and the US.

Given that nuclear submarines exceed diesel-electric submarines in terms of endurance, range and speed, the acquisition of SSNs is clearly not intended for a narrow role defending and deterring aggression in Australia’s backyard. They will also strengthen the broader US-led response to Beijing’s growing power, assertiveness and military presence in the Indo-Pacific. More than that, it is difficult to imagine Australian SSNs developed under the Aukus pact not being active participants in the event of a future conflict in the region involving the US.

Feathers have been ruffled, and not just China’s

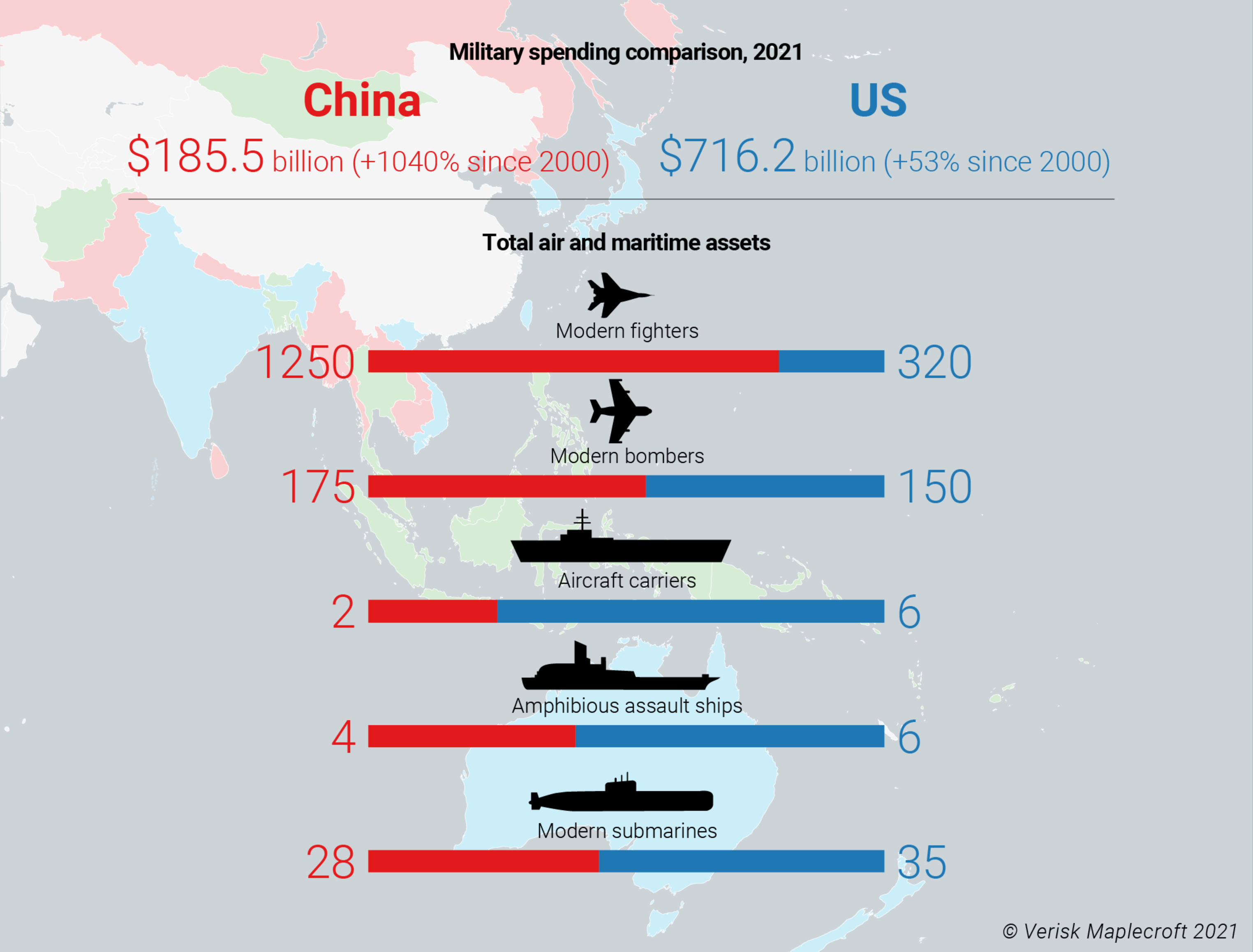

The announcement of the Aukus pact is just the latest signal that tensions between Canberra and Beijing are here to stay, and the latter will view Australia’s acquisition of SSNs as an escalation. China has already accused Australia, the US and UK of intensifying an arms race and damaging regional peace and stability; Chinese state media quoted an unnamed Chinese official suggesting that Australia would no longer be viewed as a non-nuclear power by China and Russia, and could find itself as a target of nuclear strikes in the event of a conflict. In practice, the arms race was already well underway, with Beijing upping defence spending and unveiling military assets at a remarkable rate over the last decade (see visual).

In our view, minor symbolic disruption to the bilateral iron ore trade is a plausible, if still unlikely, avenue that Beijing could use to show its displeasure. But meaningful disruption to the iron ore trade remains a remote prospect, at least until Beijing has developed alternative sources of supply.

Australia’s regional allies and partners will be absorbing the news, with the move to nuclear propulsion likely to generate friction with New Zealand and the Pacific island states, which have a deep aversion to nuclear technology and a commitment to non-proliferation. By contrast, proponents of SSN development in South Korea and even Japan may find their cases strengthened by the Australian precedent. Early statements from Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur were wary, while Singapore was more positive, but Canberra will have to work hard to reassure Southeast Asian neighbours that it takes their perspective seriously after blindsiding them.

The long build time for these nuclear submarines means there will be no quick boost to Australia’s military capacity, but a qualitative shift is nonetheless underway.

Broad domestic support

A federal election is due in Australia over the next eight months, and it could therefore be a Labor government taking these fundamental decisions. Nuclear technology is a tricky topic for the opposition, sure to generate friction from the left of the party and attacks from the Greens. But opposition leader Anthony Albanese was quick to confirm bipartisan support in principle, pending further specifics. This reflects the broad consensus in Australian politics over the changing regional security environment and the centrality of the alliance with the US.

On the domestic front, Morrison will hope that the dramatic announcement boosts his re-election prospects by shifting attention away from his handling of the pandemic. It will also counter perceptions that his failure to step up on climate policy is burning bridges with Washington and London, though at significant cost to relations with a now furious Paris.

Many key details remain to be confirmed over the next 18 months, including which vessels will be constructed and the cost and timelines. But with Aukus now very much in the public eye, each decision will be closely scrutinised, including by Australia’s parliament, while the implications are considered.