Are Turkey, South Africa and India the next IMF bailout contenders?

by David Wille,

Scores of emerging and frontier markets have requested emergency financing from the IMF as the coronavirus pandemic has choked off access to hard currency. Most governments have used the Fund’s Rapid Credit Facility and Rapid Financing Instrument to ward off balance-of-payments pressures and prop up public spending with few strings attached.

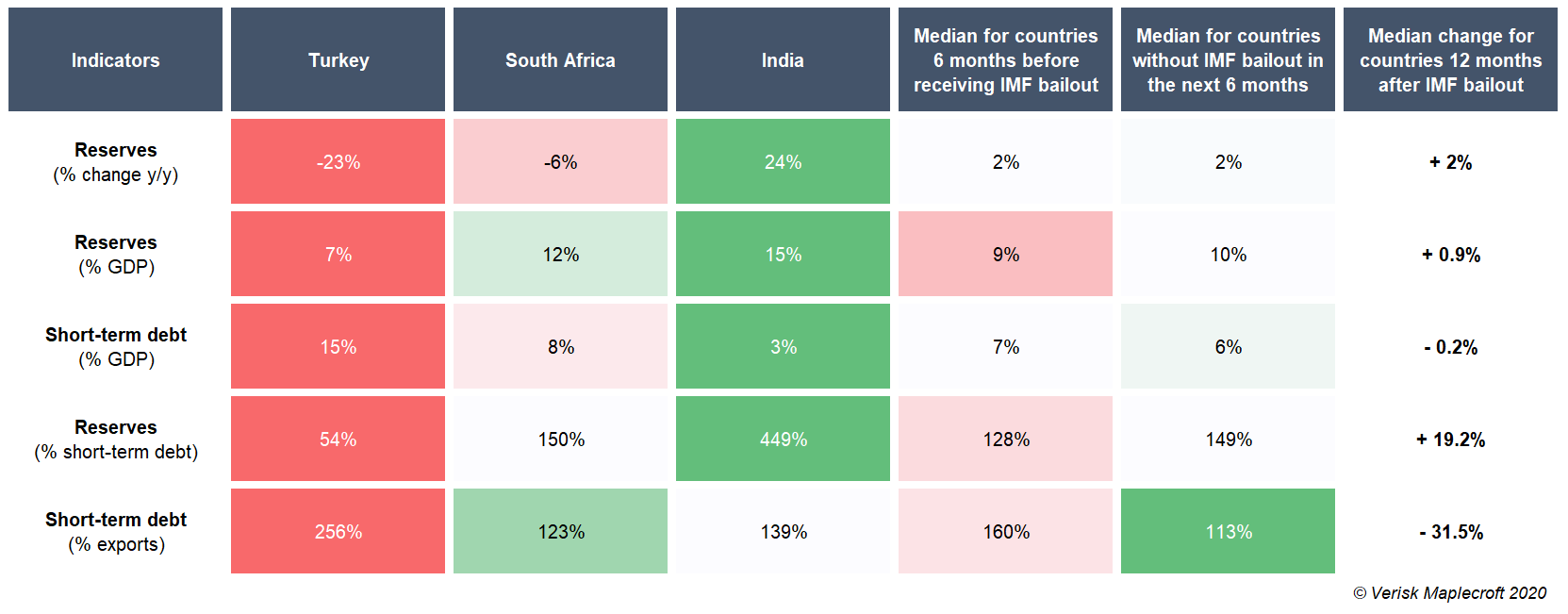

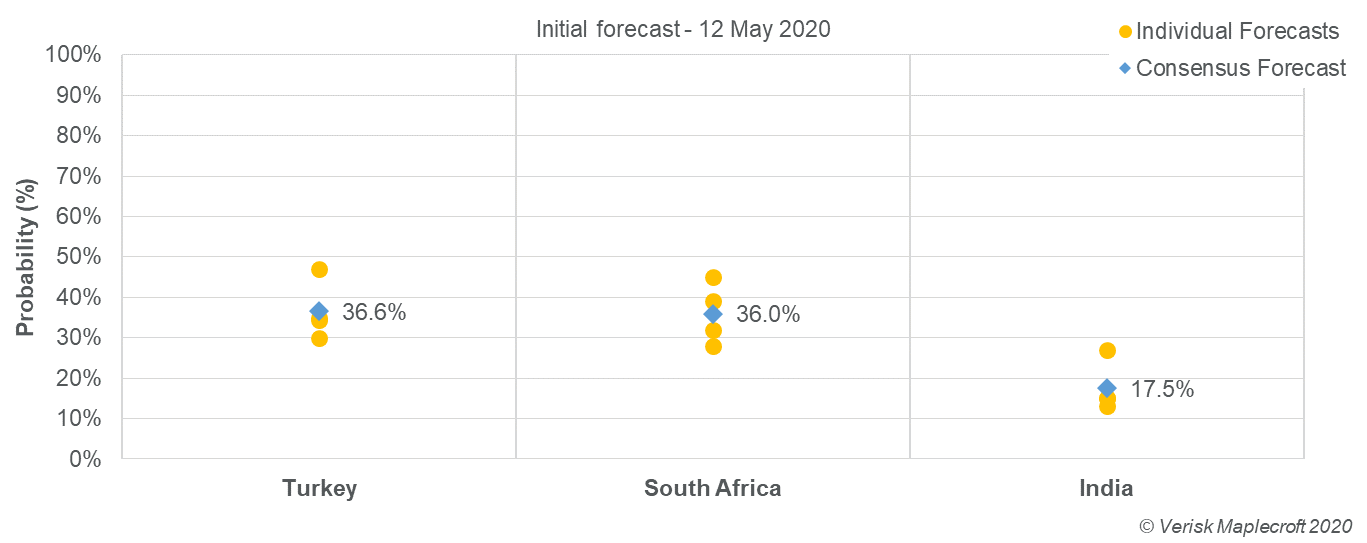

However, our team of forecasters sees a credible possibility that Turkey, South Africa and India will be forced by extreme external or fiscal pressures to commit to a fully-fledged IMF bailout before the end of 2020. We give Turkey a 36.6% probability of seeking a Fund programme as its macro-financial crisis is most acute, followed closely by South Africa. Far less likely to do so is India, which is better positioned thanks to its healthier external debt profile.

While countries that enter an IMF programme tend to see improvements in their external position in the 12 months following a deal, our base case is that leaders Erdogan, Ramaphosa and Modi would much rather not stomach the domestic political fallout from these programmes until and unless they are on the edge of the economic abyss.

Turkey: no appetite for IMF medicine for now

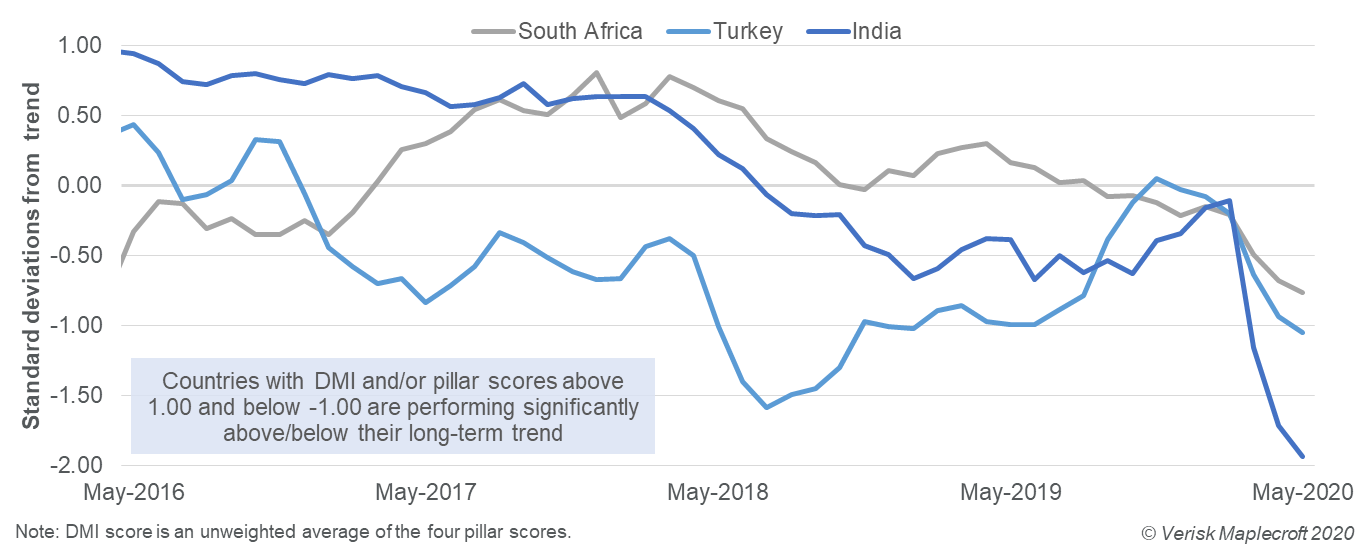

Our team gives Turkey the highest probability of seeking an IMF bailout this year because its external financing needs are most severe. The lira has lost 15% of its value since January and is at its weakest since 2018, when President Recep Tayyip Erdogan allowed the central bank to dramatically hike interest rates. The government burned through at least 35% of its reserves by mid-April yet faces nearly USD169 billion in short-term external debt maturing in the next year.

Critically, Ankara is also short of friends: the US Federal Reserve and other developed markets are unlikely to extend a hard currency swap line to a Central Bank under Erdogan’s thumb. Turkey’s currency swap with Qatar, bolstering FX reserves by around USD10 billion, only addresses about a third of Turkey’s funding gap in 2020. Without a sustained infusion of hard currency, Erdogan may be forced to permit interest rates to rise as they did in 2018 or, barring that, to resort to explicit or de facto capital controls. In such circumstances, he might see the IMF as the lesser evil.

But Erdogan is an outspoken critic of his country’s past relationship with the IMF and took pride in ending its most recent programme in 2012. The president is also loath to surrender his sway over central bank rate-setting or fiscal policy and to enhance the transparency of state accounts, all likely to be concessions required to access IMF funds. Nonetheless, Erdogan is also a consummate political survivor and may find a face-saving way to make a deal if all other options are exhausted.

South Africa: politics trump economics

South Africa, though not yet in the same dire financial straits as Turkey, also has substantial repayments due at the end of the year and is already counting on a USD4 billion loan as part of the IMF’s emergency lending programme. More significantly, the central bank forecasts GDP to shrink by at least 6% and unemployment to swell to as much as 40% in 2020, a devastating setback that will require the government to spend much more than it can finance through traditional channels. Meanwhile, a highly volatile rand will do little to cushion the economic blow of the pandemic. In our view, this makes broader IMF support to fund coronavirus recovery more likely.

Yet factionalism in South Africa’s ruling ANC ties President Cyril Ramaphosa’s hands. Politicians allied with former president Jacob Zuma are staunchly against seeking a wide-ranging agreement with the IMF, not least because the conditionalities attached to a deal would potentially expose them to prosecution by uncovering extensive corruption networks dating from Zuma’s rule. Because parliament elects South Africa’s president, Ramaphosa needs the support of the pro-Zuma faction to remain as head of the ANC at the party’s national general council meeting when it is held this summer.

India: best-positioned to avoid an IMF programme

Prime Minister Narendra Modi faces the same challenge of plugging a massive fiscal gap while suffering from a historically poor growth outlook and 25% unemployment. But despite a budget deficit on track to double this fiscal year, India has a relatively low overall public debt and total foreign debt load, giving authorities more latitude to access financing. As the table above illustrates, on key metrics of debt sustainability India is generally performing as well as if not better than countries that did not need an IMF bailout.

Deal or no, major EMs need relief

As economic necessity forces South Africa, Turkey and India to begin reopening before fully containing the COVID-19 outbreak, each faces three urgent financing needs: plugging gaps in their coffers and/or external accounts, supporting struggling businesses and the unemployed and paying for expanded public health measures. Whether that financing comes from the IMF or elsewhere, these governments will have to find the money. If they can't, the best they can hope for is to muddle through the economic malaise that settled over their economies even before the coronavirus pandemic, and at worst they risk writing new chapters in the annals of economic disaster.