Are Mexican avocados the next ‘conflict commodity’?

by Christian Wagner,

There is a good reason why avocados have been dubbed ‘green gold’. The fruit now constitutes a multibillion-dollar industry for Mexico, the world’s largest producer, with exports from the state of Michoacán alone reaching USD2.4 billion last year. But the exponential growth of the avocado’s popularity is a mixed blessing for Mexico’s communities and farmers. While most have benefited from record-breaking prices, many have attracted the attention of organised crime groups that are sinking their teeth into the profits.

From cultivation through to transportation, violence and corruption now pervade Mexico’s avocado supply chain – particularly in Michoacán, a long-standing hotbed for criminal violence. The similarities with conflict minerals are striking for companies that source avocados from the region. Association with killings, modern slavery, child labour and environmental degradation is becoming an increasing risk when dealing with Michoacán suppliers and growers, especially when establishing traceability is increasingly hard.

It remains to be seen if avocados will become a ‘conflict commodity’ in the eyes of consumers, but as we lay out below, the tell-tale signs are there.

Cartels fight over an increasingly desirable commodity

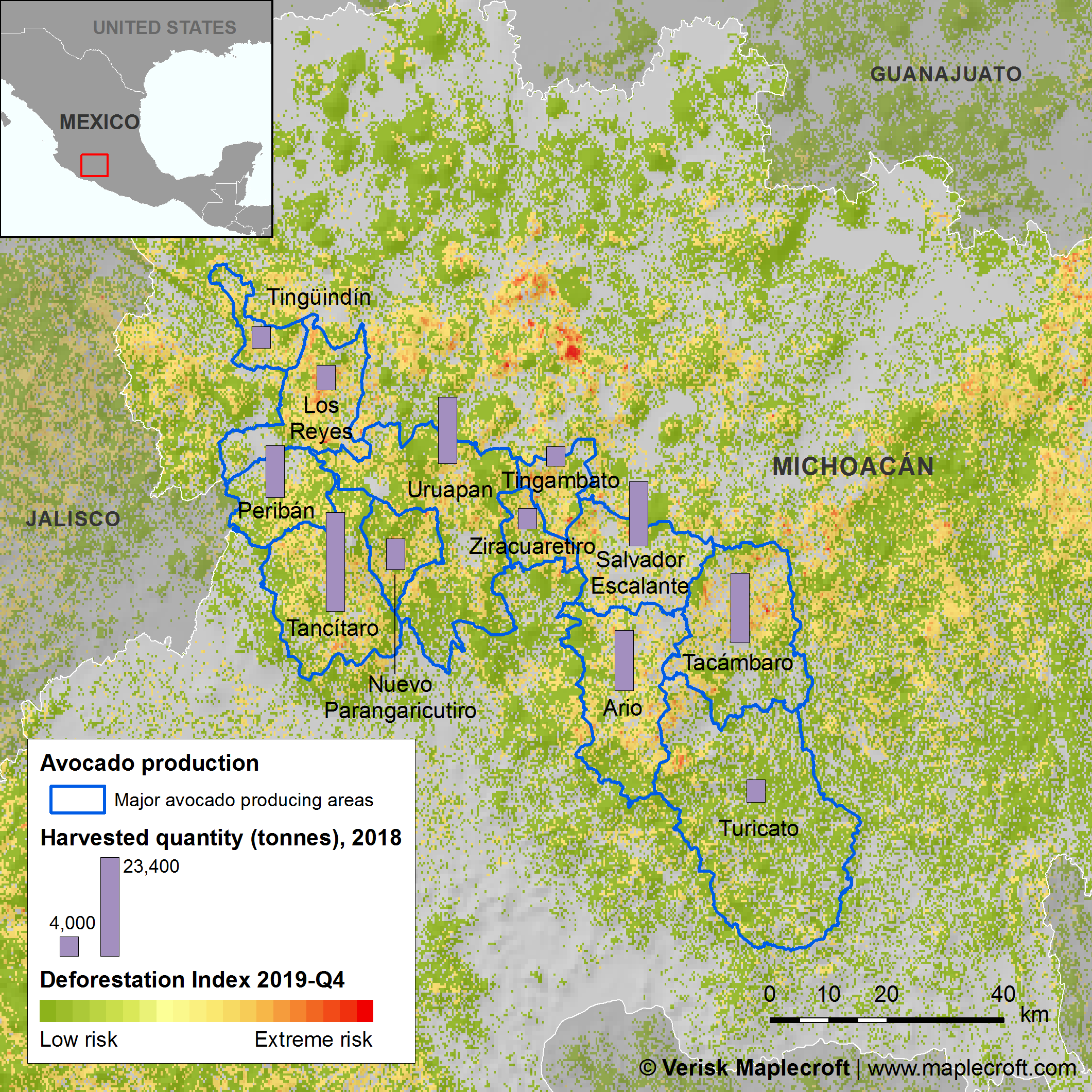

Michoacán avocados have become a prime target for drug-trafficking organisations (DTOs), which engage in both extortion and direct cultivation, usually on lands taken over from local farmers or carved out from protected woodlands.

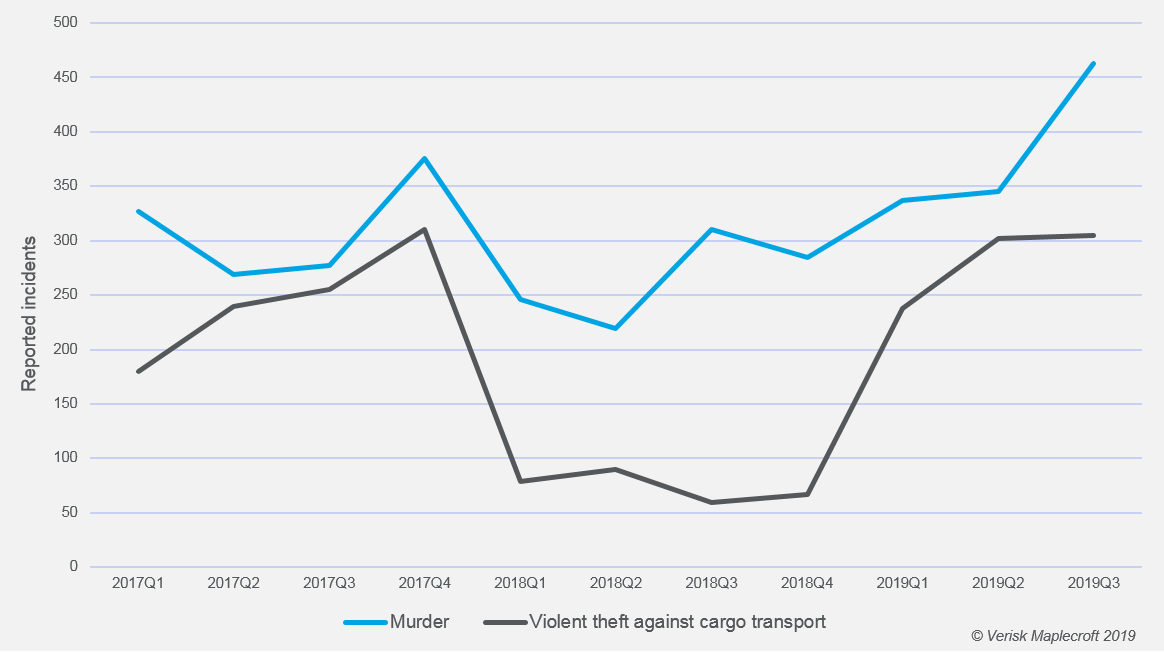

The government has been waging its War on Drugs for 13 years and many criminal groups, including DTOs, have turned to other activities. 2019 has seen the rise of criminal organisations that behave in every way as drug cartels but are not even engaged in drug-trafficking. In Michoacán, the avocado industry is providing the diversified income that criminal groups obtain through fuel theft elsewhere in Mexico. Security and criminality risks are rising in tandem as more than 12 criminal groups, including the notoriously violent Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación, fight for control over the avocado-producing regions and transport routes. The figure below shows the resulting rise in violence, driven by organised-crime related murder and particularly by turf wars.

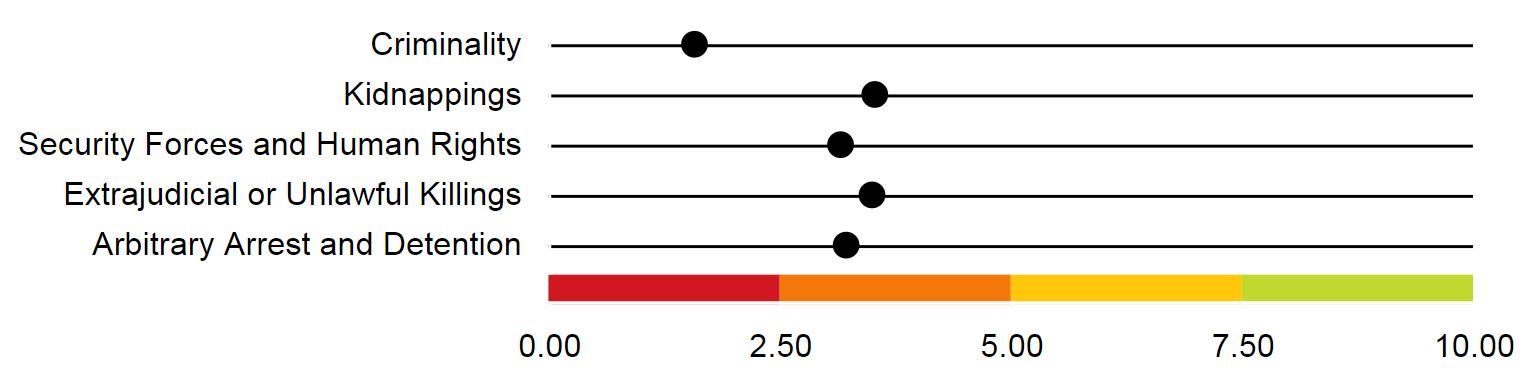

Mexico has an extreme risk score of 1.58/10.00 in our Criminality Index for 2019-Q4, making it the fifth worst in Latin America and the 9th worst globally – and we do not expect any significant improvements in the near future.

The government’s failed federal security strategy – which includes the creation of a new but under-resourced federal militarised police force – and the growing violence have driven local packers and growers to recruit and arm their own defence forces, which operate outside of the law. This increases the risk of both more violence and the potential for human rights abuses and due process violations, threatening to weaken Mexico’s performance in three of our indices: Security Forces and Human Rights; Arbitrary Arrest and Detention; and Extrajudicial or Unlawful Killings.

Risks spread through the supply chain

Trade and commercial risks also come into play when accounting for the threat of violence. In August 2019, the US Department of Agriculture had to temporarily suspend inspections in the Uruapan area after repeated threats to its employees; incidents of this type threaten the region’s certification to export the fruit and a potential ban.

The logistics side of the business is similarly exposed to criminal activity and associated disruption. Small criminal groups, lacking the resources to extort farmers or grow their own product, have turned to hijacking avocado shipments. Michoacán state authorities report that an average of four truckloads get stolen, every day. Exporters and growers face both the losses of stolen product or equipment and the risk of death or injury to their employees, disrupting the business and increasing potential costs and liabilities.

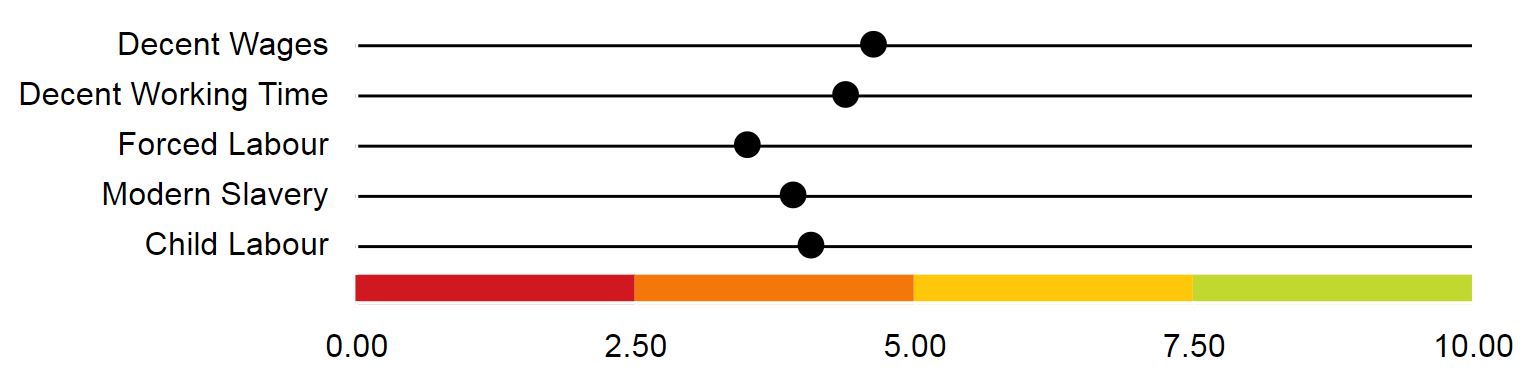

Prosecution is essentially impossible, as victims are afraid to speak up and the stolen product is impossible to track or identify once it makes its way to the market. Furthermore, social and labour risks are increasing as criminal groups become active in avocado harvesting, which pays up to 12 times the Mexican minimum wage. Mexico already features significant challenges regarding labour risks (see below), which are exacerbated by the involvement of criminal organisations.

Criminal groups often coerce pickers into temporary forced labour. Coercion against avocado pickers – including underage workers— increases the risk of violations of supply chain standards and has a negative impact on Mexico’s performance in our Forced Labour, Modern Slavery, and Child Labour indices.

The environment also under attack

Cartel activity also has a negative environmental impact, as criminal groups clear protected woodlands to make room for their avocado groves. Michoacán already struggles with deforestation challenges due to illegal logging and forest clearing for cultivation, but the participation of organised crime groups compounds the issue by making enforcement and prosecution all but impossible, and by increasingly turning forest clearing into an industrial-scale operation.

High demand, high risk

The risks associated with Mexican avocado production pose distinct supply chain management requirements for exporters and distributors worldwide. Companies trading in avocados or avocado-based products are exposed to the violation of international or corporate best-practice standards on labour, sustainability and anti-money laundering and corruption. Given the power and reach of criminal organisations, however, and the inherent weakness of Mexican institutions when it comes to enforcement, companies will be unable to eliminate the risk of handling illegally-produced fruit.

In our view, it’s some way off before avocados are considered the next ‘conflict commodity’. The issues surrounding their production and distribution are just as serious as some of those affecting 3TG minerals. But, the groundswell of public opinion simply isn’t there yet to press for action, primarily due to a lack of information. That isn’t to say avocados shouldn’t be front of mind for sustainable procurement teams operating in the food and beverage, retail and cosmetics space, they should. This is going to bite at some point, it’s just a matter of when.

Find out more about our Commodity risk data