Are crypto assets ESG-ready?

by Hamish Kinnear and Celia Willis,

Elon Musk’s declaration that Tesla will no longer use Bitcoin – due to concerns about its environmental credentials – sent the price of the cryptocurrency crashing. This came on the heels of a stern US SEC warning that investors should be wary of the “highly speculative” Bitcoin futures market.

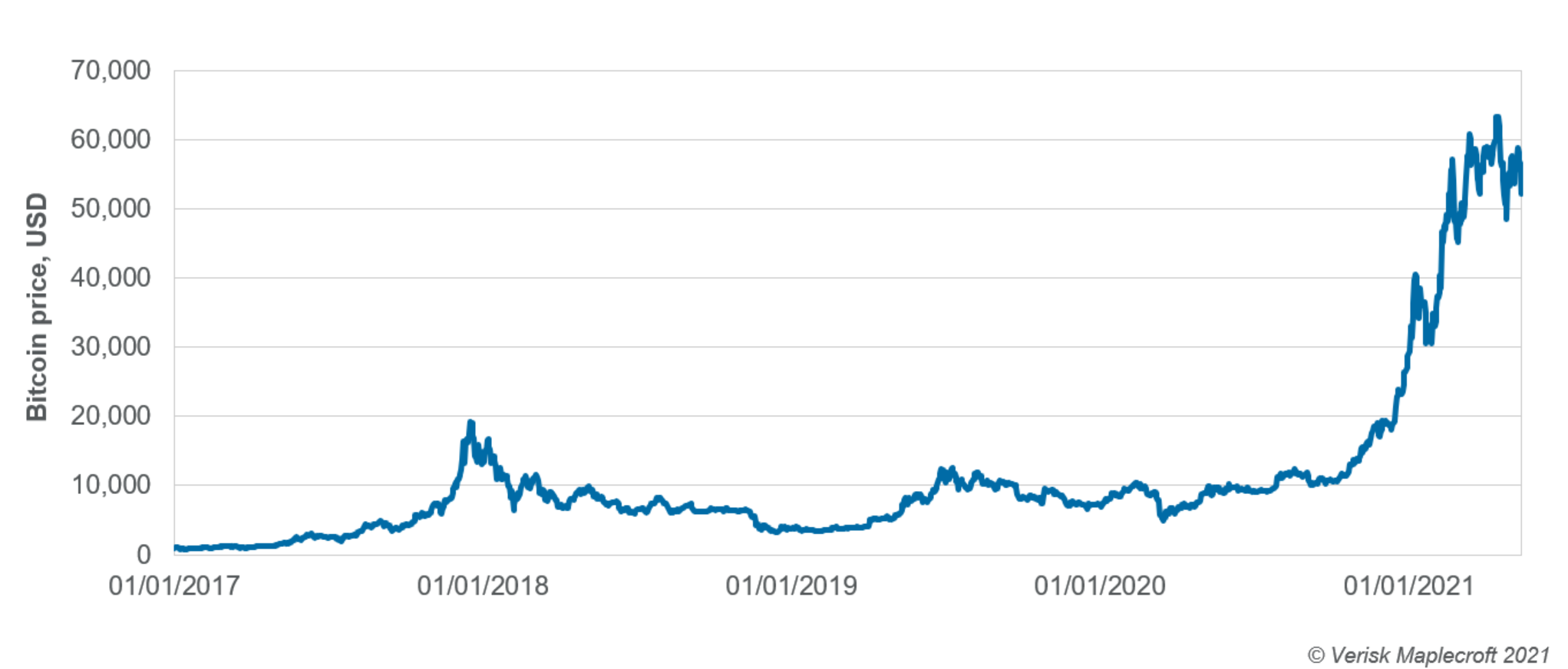

The price of Bitcoin has nevertheless risen over 600% in the past year – with interest driven by its rapid prices rises, promise of ‘inflation-proofing’ and tentative interest from institutional investors. This price rise has coincided with a flood of investment into funds based on ESG (environmental, social and governance) principles – from which Tesla, a clean energy company, has benefited.

With Musk’s latest statement, the question of whether crypto holdings are compatible with ESG principles becomes increasingly relevant. For now, it is a mixed picture. Increasing regulation, however, could help to ‘normalise’ crypto as an asset class and clarify relevant ‘S’ and ‘G’ issues. Companies issuing cryptocurrencies based on less energy-intensive tech, meanwhile, will trumpet their ‘E’ to gain a competitive edge.

Environmental impact the key concern

Intensive energy usage is built into Bitcoin’s DNA. To ‘mine’ the cryptocurrency, a computational puzzle based on a Proof-of-Work algorithm must be solved; and the complexity of these problems requires powerful computers. Indeed, the computational difficulty of mining Bitcoin is part of its value proposition, as it confers a precious quality on the cryptocurrency that is analogous to a more traditional store of value like gold. Advocates argue that this quality, matched with the fact that supply is capped at 21 million coins, will ensure BTC’s long-term survival as an asset.

The energy required is substantial, although it may not be as dirty as Bitcoin’s sternest critics imagine. Bitcoin miners in China, who account for the lion’s share of mining activity, draw not only on energy produced at coal-fired power stations, but electricity produced at China’s enormous hydroelectric facilities. Neither does Bitcoin’s intense energy use make it unique in the tech world: data centres (hosting servers, storage drives and cooling systems) consume around 200 TWh annually.

Nevertheless, the precise proportions of green to fossil fuel-energy in use is unclear – as loose global regulation worldwide means that the relevant data isn’t comprehensively tracked. What is clear, however, is that increasing mining activity spurred by price rises will put more demand on local grids. This, in turn, will inevitably attract the increasing scrutiny of global governments looking for ways to increase energy efficiency and move away from fossil fuels.

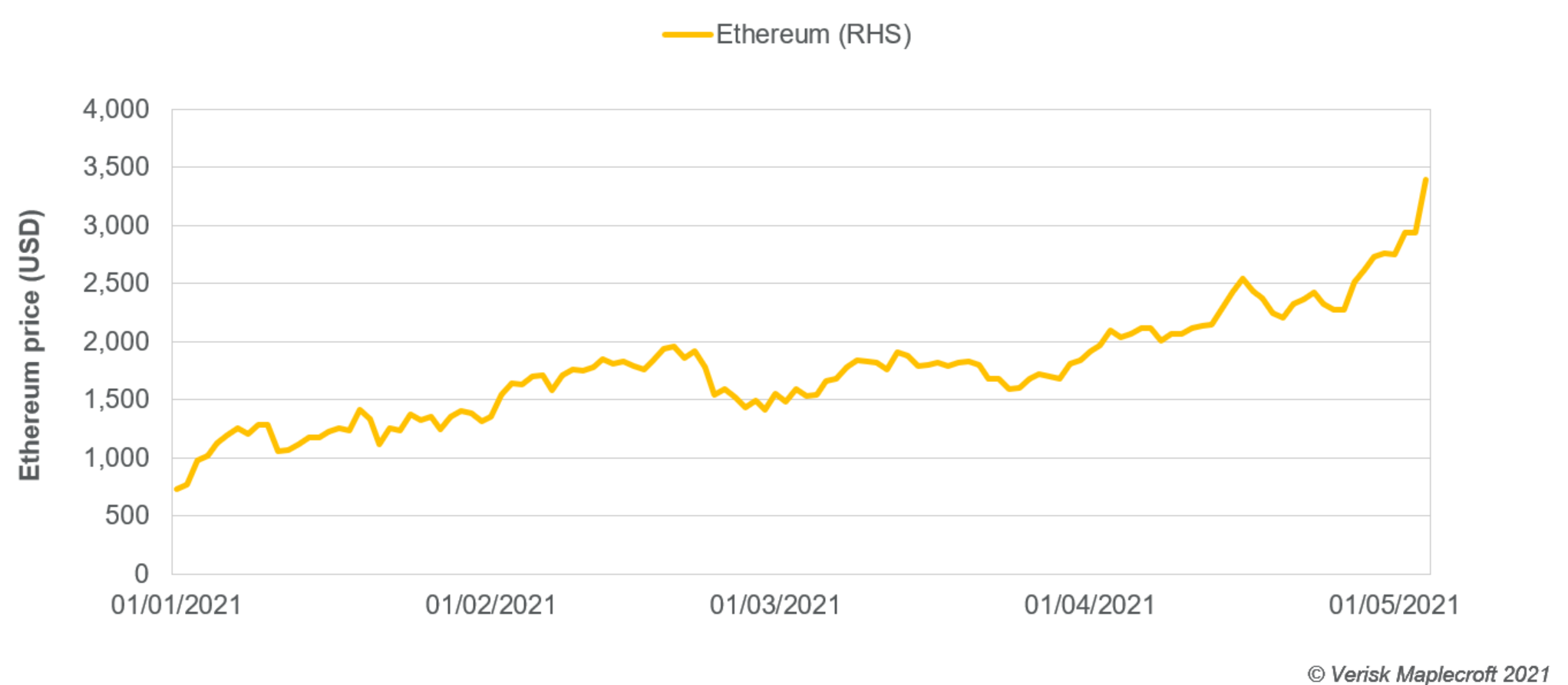

There are, however, less energy-intensive ways to operate cryptocurrencies, and rivals to Bitcoin are moving in this direction. Ethereum, the second largest cryptocurrency by market cap, is due to shift to a Proof-of-Stake algorithm over the next year, which advocates claim will significantly reduce its energy consumption. Ripple, a US tech company, also touts XRP, a rival cryptocurrency, as a greener alternative to Bitcoin due to its use of less energy-intensive technology.

This ESG edge could enable Ethereum, undergoing its own price surge (see below), and XRP to eat away at Bitcoin’s market share in the coming years, particularly if new regulations cap or tax the energy use of crypto mining operations.

Mixed approach to regulation creates governance uncertainties

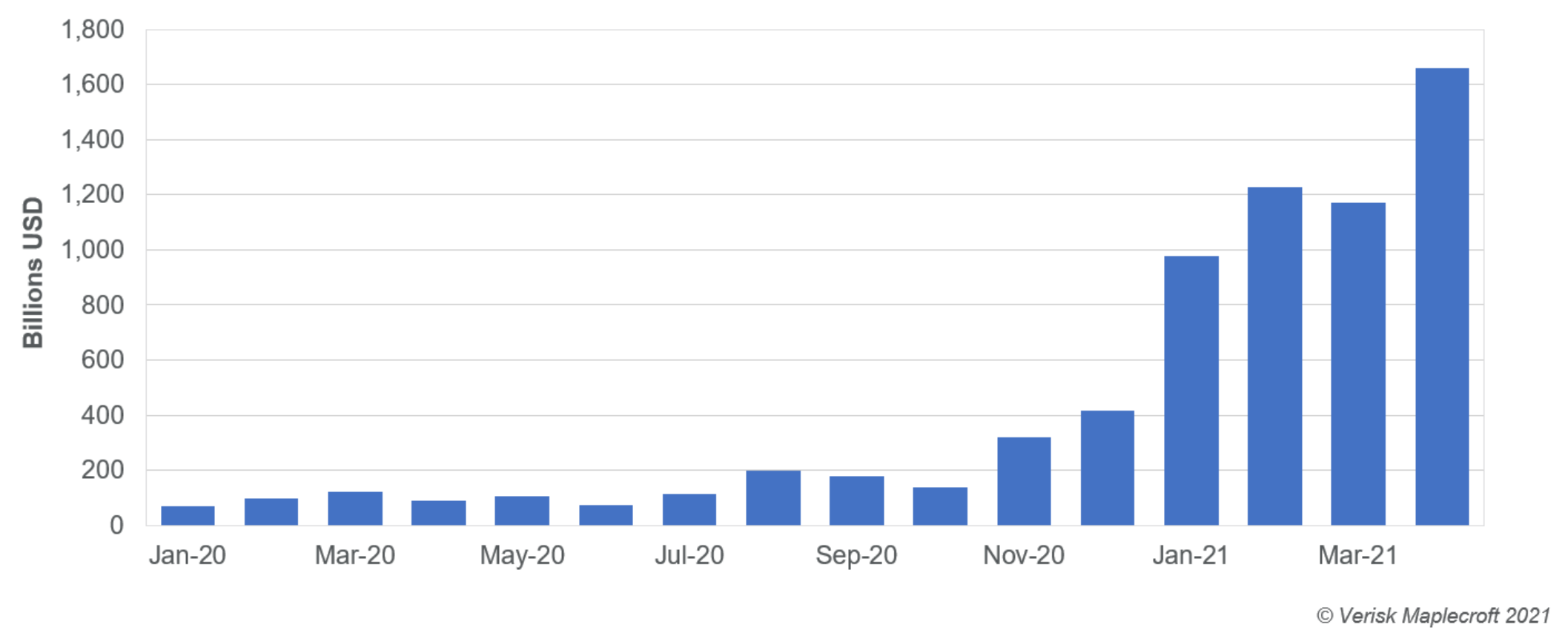

Trading on crypto exchanges soared to USD1.66 trillion in April, up from USD90bn a year ago, as Bitcoin and its rivals attract the interest of institutional investors.

Unsurprisingly, this has drawn the attention of governments and financial regulators, who harbour reservations over Bitcoin and crypto’s potential use in criminal activity, the circumvention of capital controls and its ownership concentration.

In Turkey, for example, investors flocked to Bitcoin in 2020 as they attempted to protect their savings against rising inflation – which soared above 17% in April. Last month the CBRT, citing possible “irrevocable” damage and significant transaction risks, announced legislation banning the use of cryptocurrencies for goods and services. The government, by defining crypto as an asset rather than a currency, has removed the option of crypto being used as a medium of exchange – a move that won’t necessarily disappoint Bitcoin enthusiasts, many of whom now view Bitcoin primarily as a store of value like gold, not as a means of exchange.

Western financial regulators and central banks have, by and large, refrained from imposing hard limits on the trade of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. However, neither have they introduced a comprehensive regulatory framework for crypto, which has no precise legal definition on which regulators can base decisions. The emergence of ever more sophisticated financial products on crypto trading platforms, including futures and crypto-backed loans, is making the lack of regulation unsustainable.

Ultimately, it is now a make or break moment for crypto, as regulators decide whether to crack down on crypto derivatives and loans or create a regulatory framework. The former could kill off interest from institutional investors, the latter would supercharge it as crypto assets are legitimised.

The other main hub of crypto activity – China – is on a varied regulatory path. The country, where most Bitcoin mining takes place, initially took an uncompromising approach to regulating cryptocurrencies, with the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) banning financial institutions from handling Bitcoin transactions. Regulation tightened further between 2017 and 2019, with domestic crypto exchanges and Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) being prohibited – the justification being that ICO financing is public financing without approval, an act illegal in China.

Since that high-water mark, however, China has moved in the other direction. A plan to outlaw crypto mining was scrapped in November 2019 as President Xi Jinping set out plans for China to dominate blockchain technology globally. The PBoC, despite retaining the restriction on crypto trading, recently described Bitcoin as an “investment alternative”, hinting that it considers crypto an asset as opposed to a rival currency. Meanwhile, China has stepped up its efforts to issue a ‘digital yuan’ in a bid to internationalise the Chinese currency and be the first to issue central bank digital currency (CBDC).

Increasing regulation could help to clarify the ESG profile of crypto

Where China leads, others could follow. Instead of rejecting crypto outright, global governments may seek to classify private crypto offerings as a tradable asset class, not a currency, then issue their own central bank digital currency (CBDC) based on similar tech. This will be far away from the original intention for Bitcoin and its fellow travellers: a decentralized currency unattached to government fiat. But if crypto becomes ‘just another asset class’, it will make the job of assessing crypto’s ESG credentials far easier for investors.