Increased repression in Africa will dampen destabilising impact of pandemic

by Indigo Ellis and Ed Hobey-Hamsher and Nick Branson,

Africa’s leaders are used to surviving economic and political crises. This gives them the experience and resolve they need to manage the acute public health challenge created by COVID-19. The trajectory of the pandemic across the continent remains unclear but we don’t expect its effects to cause radical upheaval to the political culture.

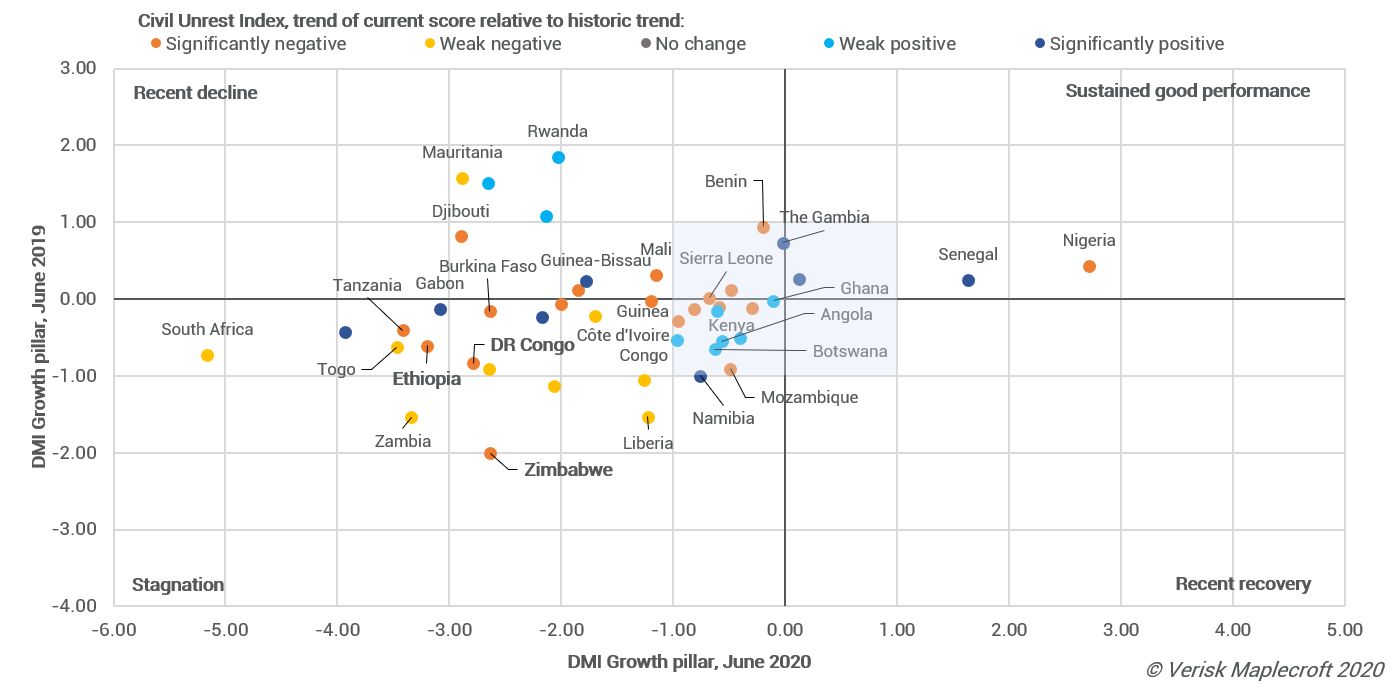

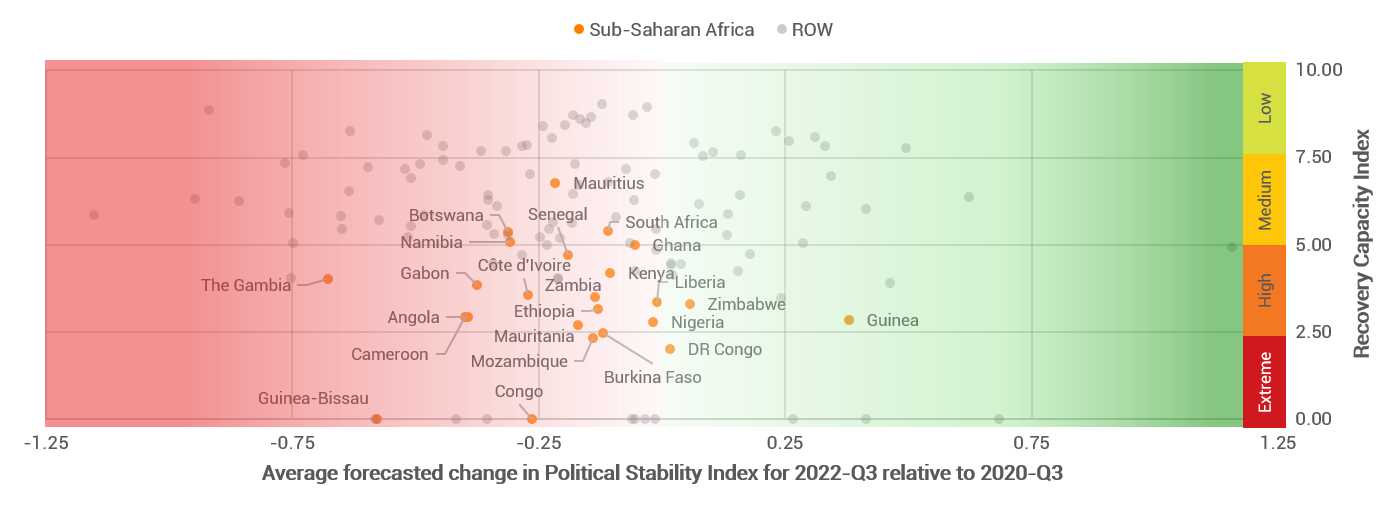

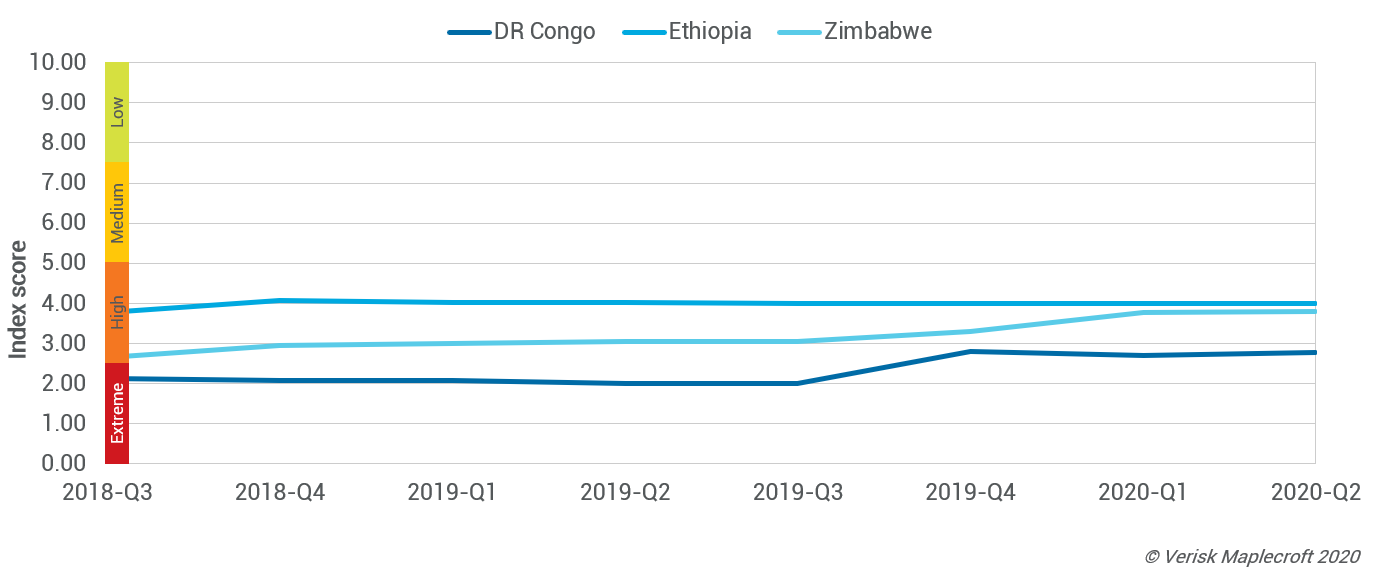

Our data shows that COVID-19 poses the greatest threat to the regimes in DR Congo, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe. This can be explained partly by these nations’ low recovery capacity in the face of the pandemic, but also by their poor economic growth and existing political instability and civil unrest. These three countries are imperfect democracies, reliant on repression to maintain the primacy of central government. By combining our Civil Unrest and our Dynamic Macroeconomic Index in the chart below, we can show these nations’ increasing instability and stagnating growth.

Despite the challenges facing DR Congo, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe, rather than government collapse or societal upheaval, we anticipate a continuation of the current political direction, with increasing repression to counter worsening divisions.

Worsening of societal divisions increases chance of more frequent violence and disrupted policymaking

COVID-19 has not created new divisions but has exacerbated existing ones. In Ethiopia, the killing of Oromo musician Hachalu Hundessa in June and the violent unrest it triggered has its roots in long-standing tensions between the Oromo and Amhara ethnic groups. The heavy-handed response of the state threatens to antagonise Oromo nationalists. The incommunicado detention of senior Oromo politicians comes at a time when the legitimacy of Ethiopia’s ethno-federalist model is under question. Exacerbating existing ethnic divisions increases the risk of more frequent, prolonged and geographically spread violence.

In Zimbabwe, popular frustration with ZANU-PF rule culminated in an attempted mass opposition demonstration on 31 July. President Emmerson Mnangagwa and his military backers responded with their customary brutality, fuelling further outbreaks of violence disruptive to businesses. Protracted disturbances will galvanise the military and strengthen the hand of the former officers who installed Mnangagwa via a coup in 2017. This will widen divisions in the ZANU-PF politburo and cabinet, disrupting policymaking, albeit without threatening the regime.

The pandemic has given cover for the FCC, ex-president Kabila’s party, to exert pressure on President Félix Tshisekedi’s Cach grouping in DR Congo. Each side is attempting to enact its own measures to further its primacy, including through manipulating appointments at the electoral commission. Ongoing protests countered with heavy security responses and backroom dealings will test the stability of the ruling coalition as the 2023 presidential election approaches. We foresee challenges to the regulatory environment as Tshisekedi scrabbles to maintain control over key industries, including mining.

Rule of law abuses will remain a tried and tested method to temper instability

Governments will continue to control the political space. In Ethiopia, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed used an unprecedented constitutional manoeuvre to legitimise remaining in office until the threat of COVID-19 recedes enough to allow the indefinitely delayed election to take place.

In Harare, the tussle between Mnangagwa and his deputy Constantino Chiwenga looks set to continue throughout 2020 as the president plans to amend the 2013 constitution. Mnangagwa’s reforms would block the introduction of presidential running mates ahead of the next vote in 2023, thus denying Chiwenga a place on a ZANU-PF slate.

Judicial reform and manipulation of electoral commission appointments have been drivers of protests in the Congolese capital Kinshasa.

We expect all three countries to slide into the higher risk category on our relevant governance indices (see chart below).

Changing demographics increase urban disruption risks in the longer term

The slide in governance standards will only continue as we expect COVID-19 to change demographic structures over the next five years. The young, those best-placed physiologically to survive the pandemic, will be at the forefront of urban migration driven by the impact of the pandemic on food production and horticulture. Young urban populations will place demands on governments to meet their socioeconomic demands. They are unlikely to tolerate the crime, contagion and congestion that would prevent them realising their aspirations. Increased urban unemployment reduces the opportunity cost of unrest. Younger populations retain less loyalty to parties that emerged from national liberation movements as they have no experience of previous regimes.

In responding to COVID-19, we therefore expect the governments of DR Congo, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe to draw from the same playbook used to retain power through political and economic turmoil. Any concessions they offer will be insufficient to mute public discontent, and we expect younger populations to embrace civil unrest to deliver change. For companies with interests in these countries, political and regulatory risks will rise, as will the possibility of association with increasingly repressive and corrupt regimes.