A dangerous new era of civil unrest is dawning in the United States and around the world

Verisk Perspectives

by Tim Campbell and Miha Hribernik,

As socioeconomic fallout from COVID-19 mounts, we expect the ranks of global protesters to swell over the next two years and unrest to sweep across developed, emerging, and frontier markets alike.

According to data from our Civil Unrest Index Projections, 75 countries will likely experience an increase in protests by late 2022. Of these, 34–predominantly in Europe and the Americas – will likely see a particularly significant deterioration–defined as a projected decrease of 0.5 or more on our Civil Unrest Index score. Following a tense summer, the United States has seen its standing on the index sharply deteriorate — falling from the 91st riskiest jurisdiction in our Civil Unrest Index in the second quarter of 2020 to the 34th most by the fourth quarter of 2020. While we expect unrest in the United States to gradually subside by the second quarter of 2021, it will likely continue to remain significantly elevated compared to historic trends over the next two years.

Globally, the increase in protests is expected to be primarily driven by food insecurity and the erosion of mechanisms that have historically defused tensions, such as freedoms of assembly and the press, and an independent judiciary. We expect the surge in instability to take place against a backdrop of a painful post-pandemic economic recovery that will likely inflame existing public dissatisfaction with governments.

What is the Civil Unrest Index?

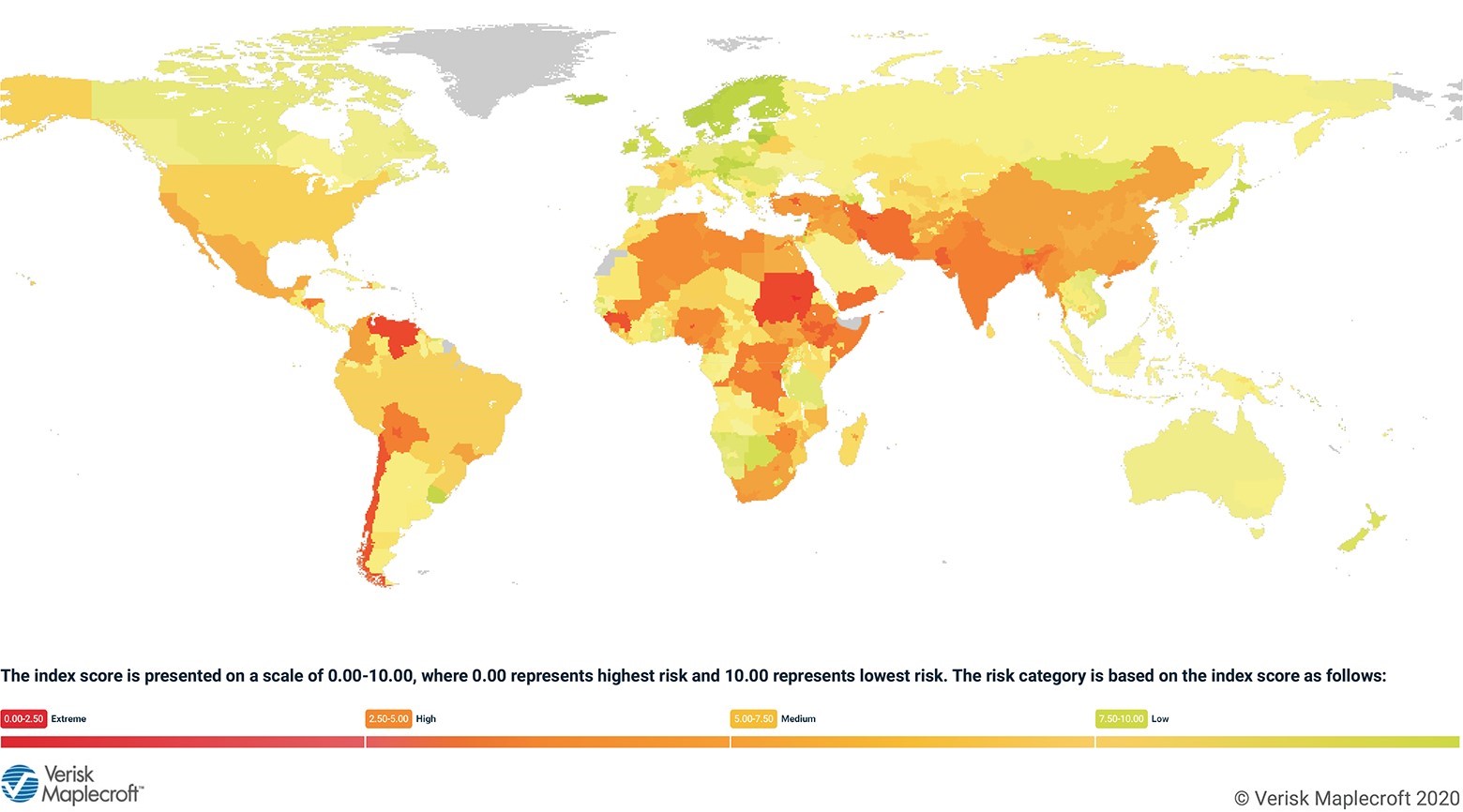

The index assesses the risk of disruption to business caused by the mobilisation of societal groups in response to economic, political, or social factors. It includes a spectrum of incidents of unrest, from peaceful protests to violent mass demonstrations and rioting. The index includes risk assessment at the country level (e.g. the average risk of unrest in the United States as a whole) as well as the sub-national level (e.g. the risk in Minnesota versus the risk in New York State).

The index scores are derived from a survey assessing key components of the drivers of unrest–such as cuts to food and fuel subsidies, and inflation–alongside mechanisms that enable the peaceful channelling of discontent (such as an independent judiciary and press), and actual outcomes of civil unrest – i.e. the frequency and physical impacts of unrest.

Unrest has topped pre-pandemic era, with more expected to come

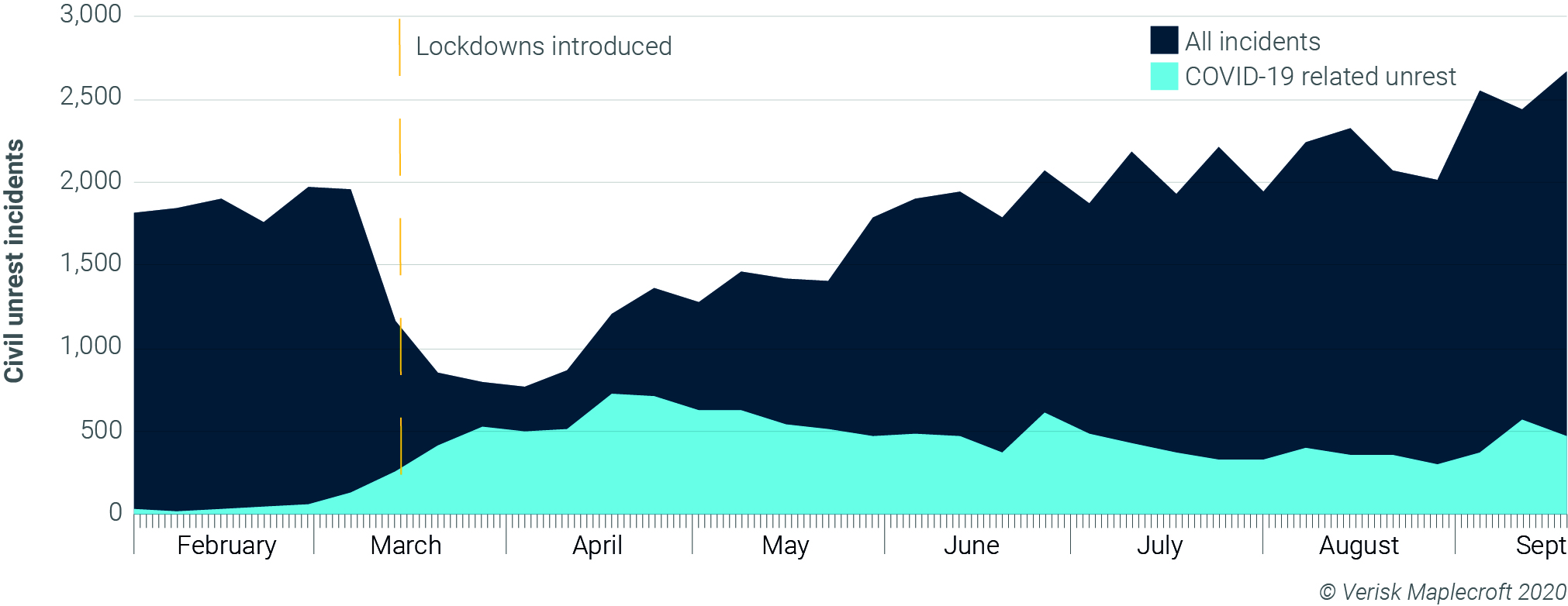

As the pandemic began to spread across the globe in March 2020, the number of protests initially fell due to the widespread introduction of lockdowns. As the figure below shows, most protests that did take place during this initial stage of the pandemic were mainly motivated by the direct impact of COVID-19 – such as food insecurity, job losses, or frustration over lockdowns.

But protests quickly resumed worldwide as long-standing grievances resurfaced. Simply put, anger over pre-existing socioeconomic issues, rising unemployment, government missteps in coronavirus response, and other problems exploded once the initial shock of the pandemic subsided and lockdowns relaxed.

As Figure 1 below shows, the total number of protests worldwide exceeded pre-pandemic levels by the end of July. With many countries still in lockdown and the full economic shock of the outbreak yet to be felt, we expect the number of protests to continue to rise over the coming months.

Recent history indicates that the economic disruption and direct damages to assets and property resulting from civil unrest can be quite costly. For example, the protests in Chile during October-November 2019 caused disruptions and direct damage to assets and property, leading to an estimated $1.5 billion in business losses.

Given this, we expect that the events of 2020, and perhaps beyond, may incur extremely high costs.

Europe and Americas projected to experience biggest waves of protests

With no end to the pandemic-induced economic downturn in sight, the rebound in protests is unlikely to subside any time soon. Our two-year Civil Unrest projections expect 75 countries, well over a third of the 198 jurisdictions in our database, will experience an increase in civil unrest by August 2022.

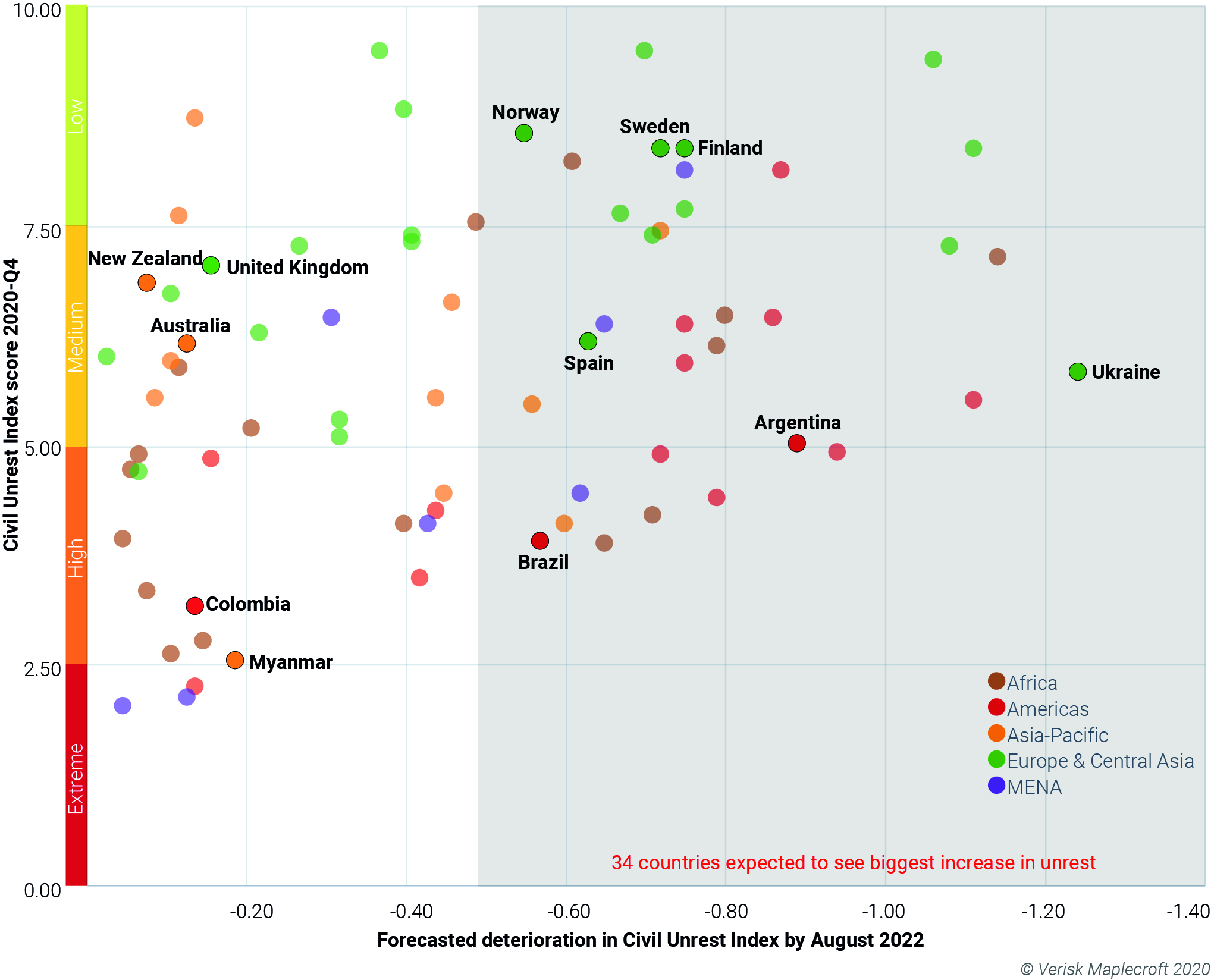

Although much of the deterioration will likely be concentrated in frontier and emerging markets, it is unlikely any region will be fully excluded from this trend. As Figure 2 below shows, even major developed economies such as Germany, Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K. are likely to experience a deterioration in the index score. However, the projected decline is expected to be mild to moderate in the majority of the 75 countries – likely resulting in, for example, a higher frequency of unrest and more damage to infrastructure and buildings. But in countries with already high levels of unrest during the fourth quarter of 2020 (e.g. Myanmar, Colombia, and Cameroon), the economic fallout will likely amplify a further worsening in an already unstable environment.

The outlook is most bleak for the 34 countries that face significant deterioration by August 2022. As shown in the figure below, almost half of these states are in Europe and Central Asia (12), followed by the Americas (10), Africa (6), MENA (Middle East and North Africa) (3), and Asia (3).

Although wealthy European markets are set to remain among the least risky jurisdictions globally by 2022, many now face the prospect of protracted unrest for the first time in recent history. Finland is projected to experience the 16th biggest rise in protests globally over the next two years, followed closely by Sweden (21st) and Norway (34rd). Growing political polarisation, a rise in social activism, and the ongoing economic slowdown will all likely contribute to a jump in tensions. But even with this increase, the Nordic countries will likely remain low-risk destinations for corporates and investors.

The outlook is, however, projected much bleaker in Ukraine, which is expected to experience the single biggest deterioration in unrest globally, fuelled by stalling reforms and the presence of armed militant groups that will likely continue to inflame tensions on the streets. Meanwhile, we expect unrest in Spain to rebound to pre-pandemic levels, which will likely mean a return to “business as usual” in a country where protests tend to be relatively frequent.

View the full Verisk Perspectives report now

In the meantime, the Americas are heading towards the biggest economic contraction of any region in 2020. Latin American countries, in particular, face a toxic mix of fiscal constraints from falling tax receipts, alongside spiralling demands for more spending from distressed populations. We expect the fallout from the pandemic is going to worsen basic inequalities and act as a catalyst for further unrest. In a region with high levels of poverty and worker informality, more people will likely be pushed into lower-paid, unstable, part-time, and/or informal jobs.

The emergency spending that governments have implemented is expected to eventually come to an end over the coming months. We expect the belt-tightening to also lead to a removal of food and fuel subsidies–a textbook catalyst of unrest. Argentina, projected to experience the 8th biggest deterioration in unrest globally by August 2022, is one of the countries most exposed to protests driven by the withdrawal of government aid. Meanwhile, in Brazil, growing political polarisation and the massive economic and health toll of the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to deepen the risk of protests from both sides of the political divide.

What about the United States?

Fueled by the pandemic, disquiet over socioeconomic inequality, and protests against racial discrimination (see Figure 3 below), the United States has recorded one of the biggest deteriorations on our Civil Unrest Index over the past year. As recently as the second quarter of 2020, the United States was ranked 91st, but by the fourth quarter had fallen into the 34th place globally.

As the economy begins a gradual post-pandemic recovery and as tensions surrounding the 2020 election eventually recede, we expect unrest in the United States to subside during the second quarter of 2021. But even as protest rates are likely to remain broadly stable between the second quarter of 2021 and the fourth quarter of 2022, they are unlikely to fall back to pre-2020 levels, likely keeping the United States firmly within the high-risk category on our Civil Unrest Index.

Figure 3: US protests from May to September 2020

Food insecurity, weakening institutions to further fan flames

The reasons for the projected surge in unrest worldwide are often complex. While exacerbated by COVID-19 and the economic malaise it has inflicted, protests continue to be largely driven by domestic structural issues, such as socioeconomic inequality, the rising cost of living, and the rise in nativism and populism, that governments across the globe have struggled to address.

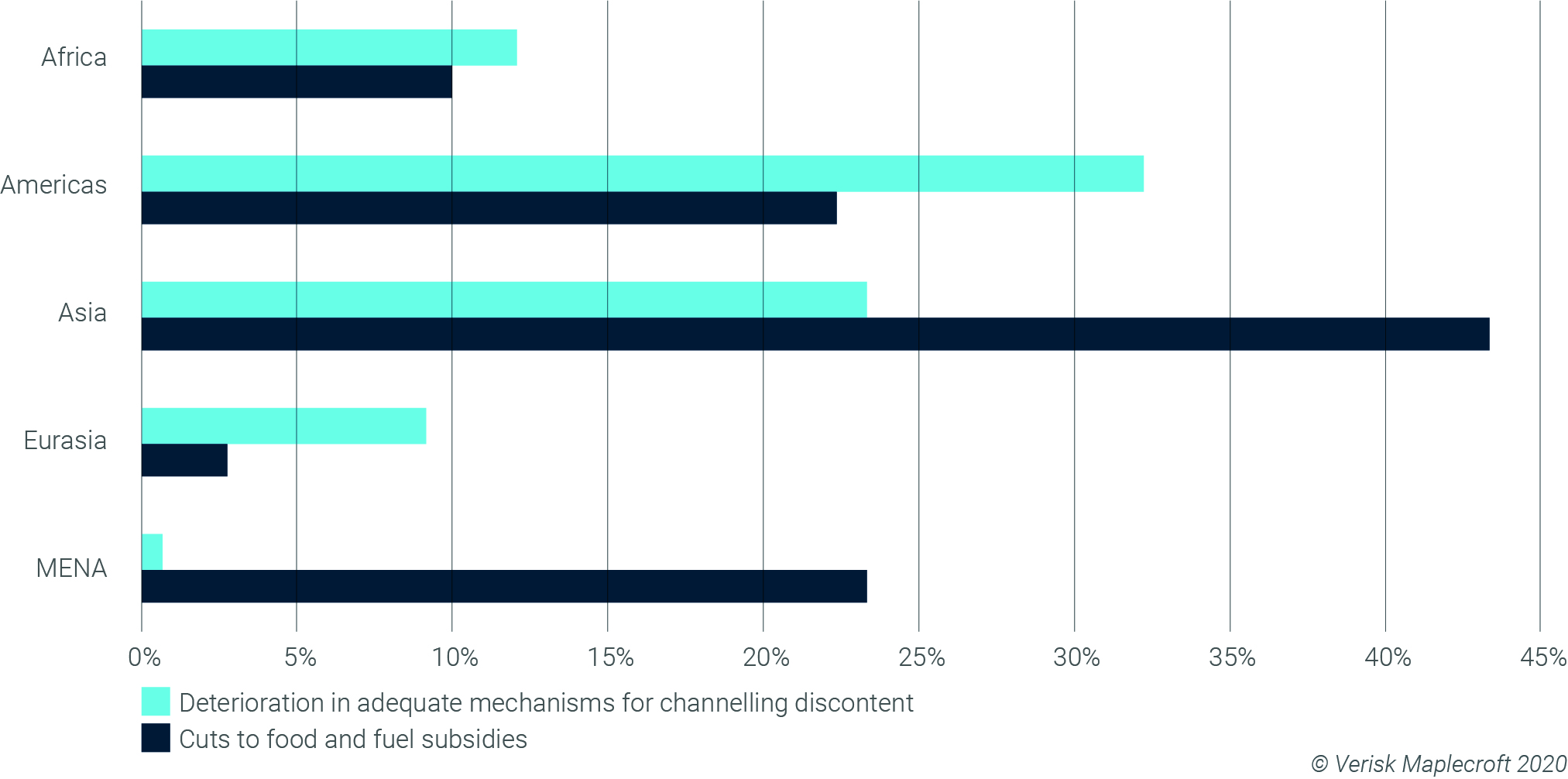

Our research suggests that reductions in food and fuel subsidies and an erosion in mechanisms for channelling discontent (such as freedom of assembly, and independent judiciary and independent labour unions) are, on average, the most significant catalysts of projected increases in unrest.

Learn more about our risk indices

Many of these factors are captured in our Civil Unrest Index projections, and the dataset includes six-month and two-year projections for individual risk drivers. By indicating which drivers of unrest are likely to deteriorate in the future, these projections can serve as an early warning sign ahead of probable spikes in unrest.

As the table below shows, among the 34 most at-risk countries, expected cuts to subsidies–reflecting a rise in the cost of living and a possible increase in food insecurity–are the most significant drivers of unrest in Asia and MENA. The erosion of mechanisms for channelling discontent, by comparison, is more significant in Africa, the Americas, and Eurasia (Europe and Central Asia). However, both issues play a key role in most of the world’s regions. The two outliers are MENA–where the significance of the latter is almost negligible–and Eurasia, where both factors have a low probability of deterioration. In the latter, much of the rise in protests is likely to stem from the aforementioned political polarisation and the post-COVID-19 economic fallout.

The apparent significance of subsidies in the prevalence of protests reflects the importance of food security for ensuring social stability. While acute food insecurity predates COVID-19 in a number of countries, the pandemic is projected to significantly exacerbate existing issues with food availability and cost. According to the World Food Programme, the number of acute food insecure people globally will soar from 149 to 270 million by the end of the year, as a result of the pandemic.

According to our Food Security Index, 26 of the countries most likely to see a surge in unrest by the fourth quarter of 2022 are exposed to at least some degree of food insecurity. The index provides a quantitative assessment of risks to the continued availability, stability, and accessibility of sufficient food supplies. Only seven states, all of them in Europe or the Americas, fall into the low-risk category.

The decade ahead is expected to be tumultuous

After a brief pause following the outbreak of COVID-19, protesters hit the streets in droves across the globe for much of the second half of 2020. But while this past year has established itself as one of the most tumultuous years in recent history, our analysis shows that the worst is likely yet to come for many countries.

Indeed, we expect 2020 to be not an outlier but rather a harbinger of things to come–not just within the next two years, but for much of the coming decade. In the most vulnerable states, from Ukraine, Argentina, Brazil, and beyond, the ranks of protesters marching against long-standing grievances will likely continue to swell, with millions of newly unemployed, underpaid, and underfed citizens, posing a risk to domestic stability; a scenario with few parallels in recent decades.