The dramatic surge in protests in 2019 has swept up a quarter of countries in its tide and sent unprepared governments across all continents reeling. According to our latest data and forecasts, the turmoil is set to continue unabated in 2020.

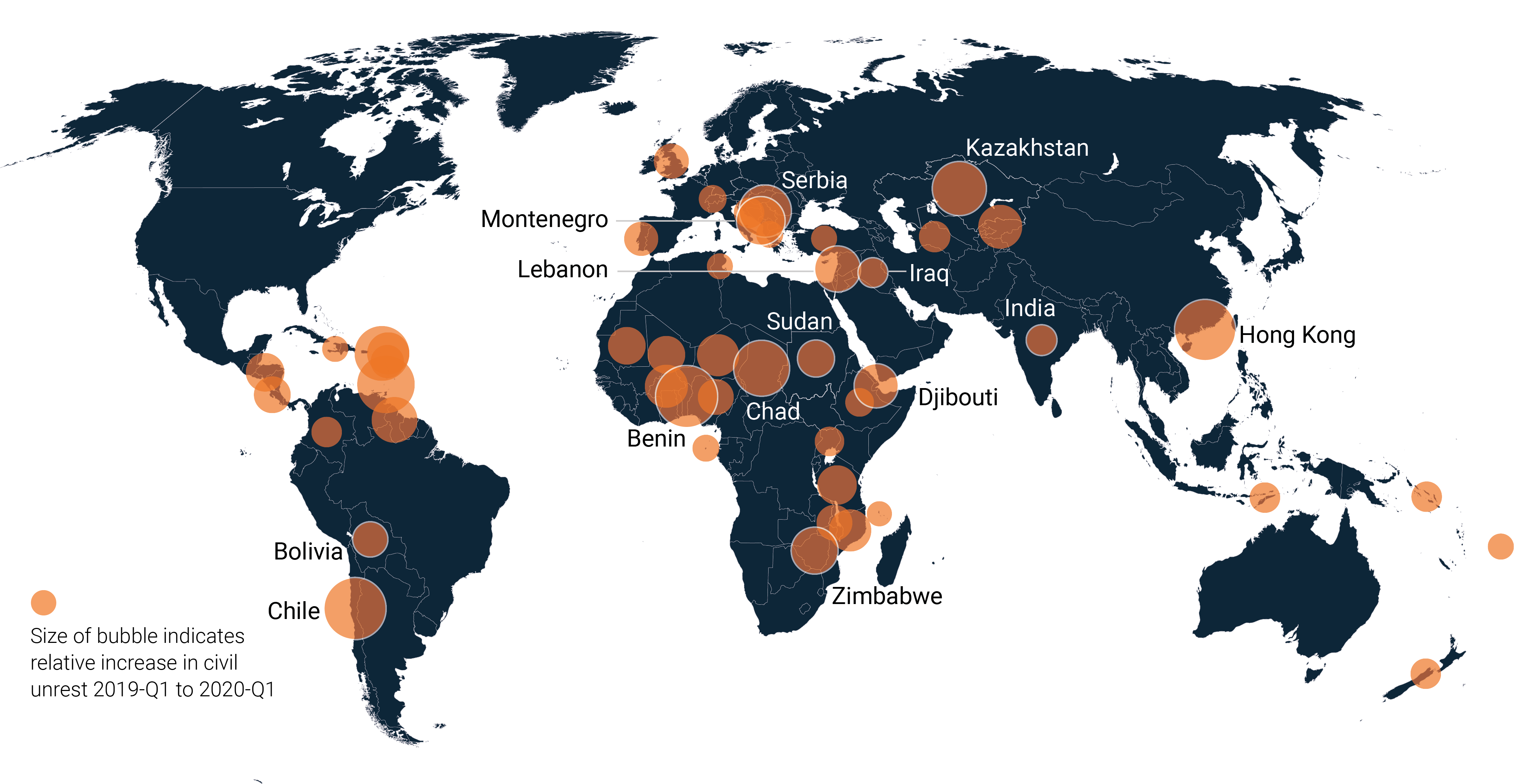

Our quarterly Civil Unrest Index reveals that over the past year 47 jurisdictions have witnessed a significant uptick in protests, which intensified during the last quarter of 2019. This includes locations as diverse as Hong Kong, Chile, Nigeria, Sudan, Haiti and Lebanon.

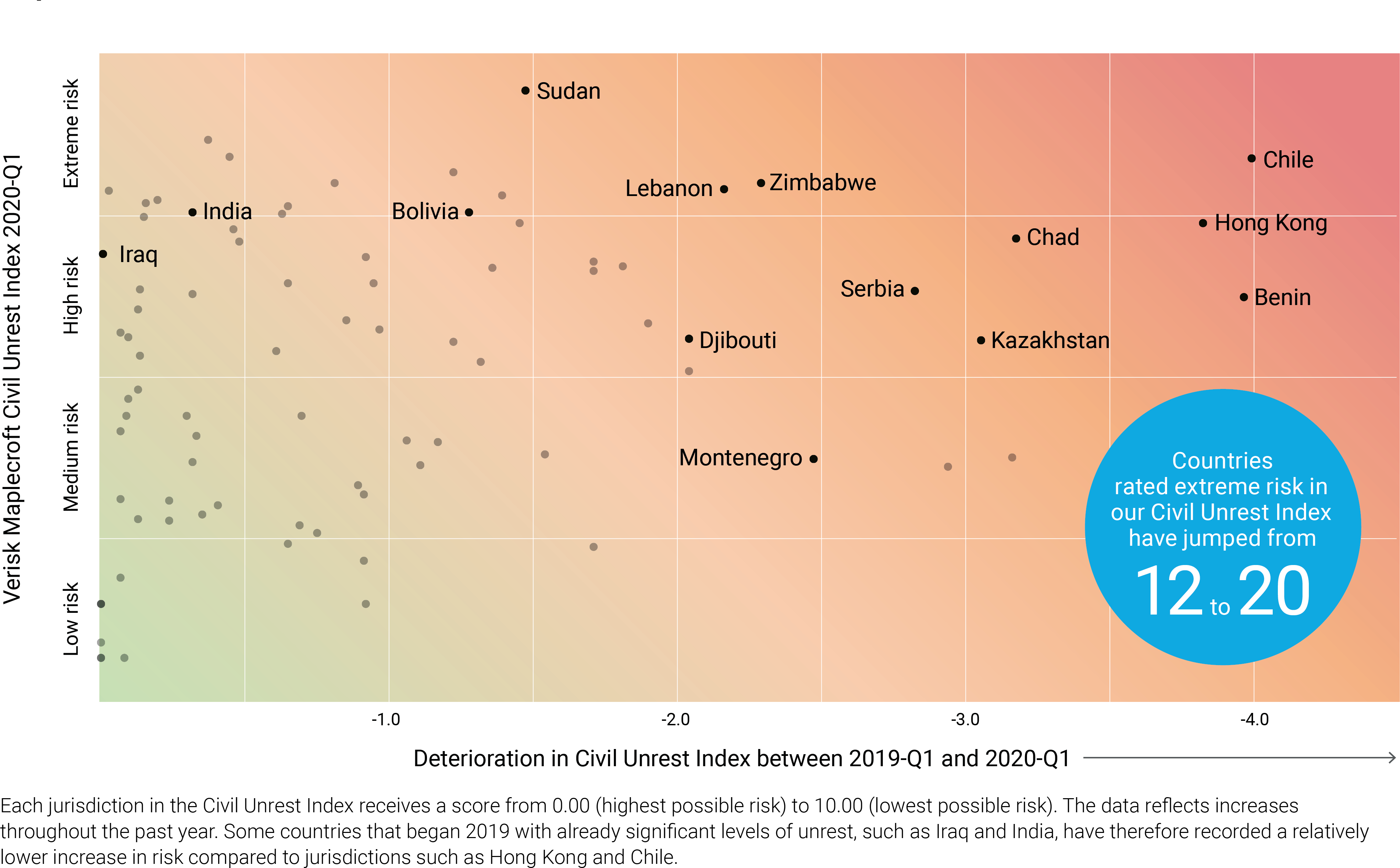

Figure 2 puts this deterioration into stark perspective, showing the flashpoints that have seen the largest increases in unrest between the start of 2019 and early 2020. During this period, Chile and Hong Kong have plummeted in the ranking of 198 countries, from 91st to 6th and 117th to 26th highest risk respectively. Other hotspots, including Nigeria (ranked 8th), Lebanon (13th) and Bolivia (21st), have also recorded some of the biggest negative swings in the index.

The only thing saving Hong Kong from dropping further in the index is that it still has some mechanisms in place for channelling discontent, including freedom of speech and a robust judiciary, even though these are being increasingly eroded. This is in contrast with many of the extreme risk countries where no such mechanisms exist. In terms of the severity and frequency of protests, though, Hong Kong sits alongside Chile as the world’s riskiest location.

Economic toll of unrest numbers in the billions of dollars

The number of countries rated extreme risk in the Civil Unrest Index has also jumped by 66.7%; from 12 in 2019 to 20 by early 2020. Countries dropping into this category include Ethiopia, India, Lebanon, Nigeria, Pakistan and Zimbabwe. Sudan, meanwhile, has overtaken Yemen to become the highest risk country globally.

An ‘extreme risk’ rating in the index, which measures the risks to business, reflects the highest possible threat of transport disruption, damage to company assets and physical risks to employees from violent unrest. Most sectors, ranging across mining, energy, tourism, retail and financial services, have felt the impacts over the past year.

The resulting disruption to business, national economies and investment worldwide has totalled in the billions of US dollars. In Chile, the first month of unrest alone caused an estimated USD4.6 billion worth of infrastructure damage, and cost the Chilean economy around USD3 billion, or 1.1% of its GDP.

Download the Political Risk Outlook 2020

Each protest is unique – but some have grievances in common

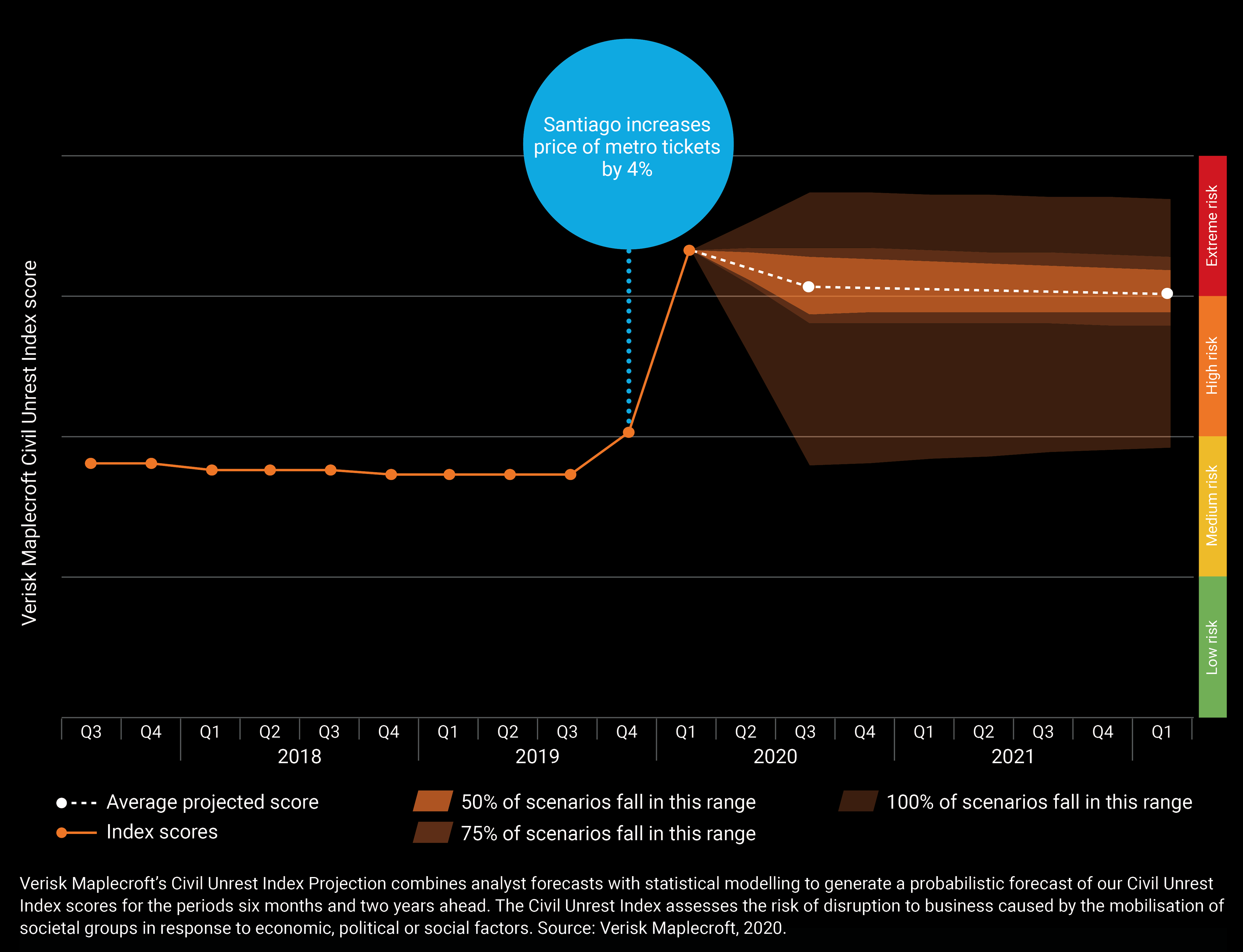

The reasons for the surge in violent unrest are complex and diverse. In Hong Kong, protests erupted in June 2019 over a proposed bill that would have allowed the extradition of criminal suspects to mainland China. However, the root cause of discontent has been the rollback of civil and political rights since 1997. In Chile, protests have been driven by income inequality and high living costs but were triggered by a seemingly trivial 30-peso (USD0.04) increase in the price of metro tickets.

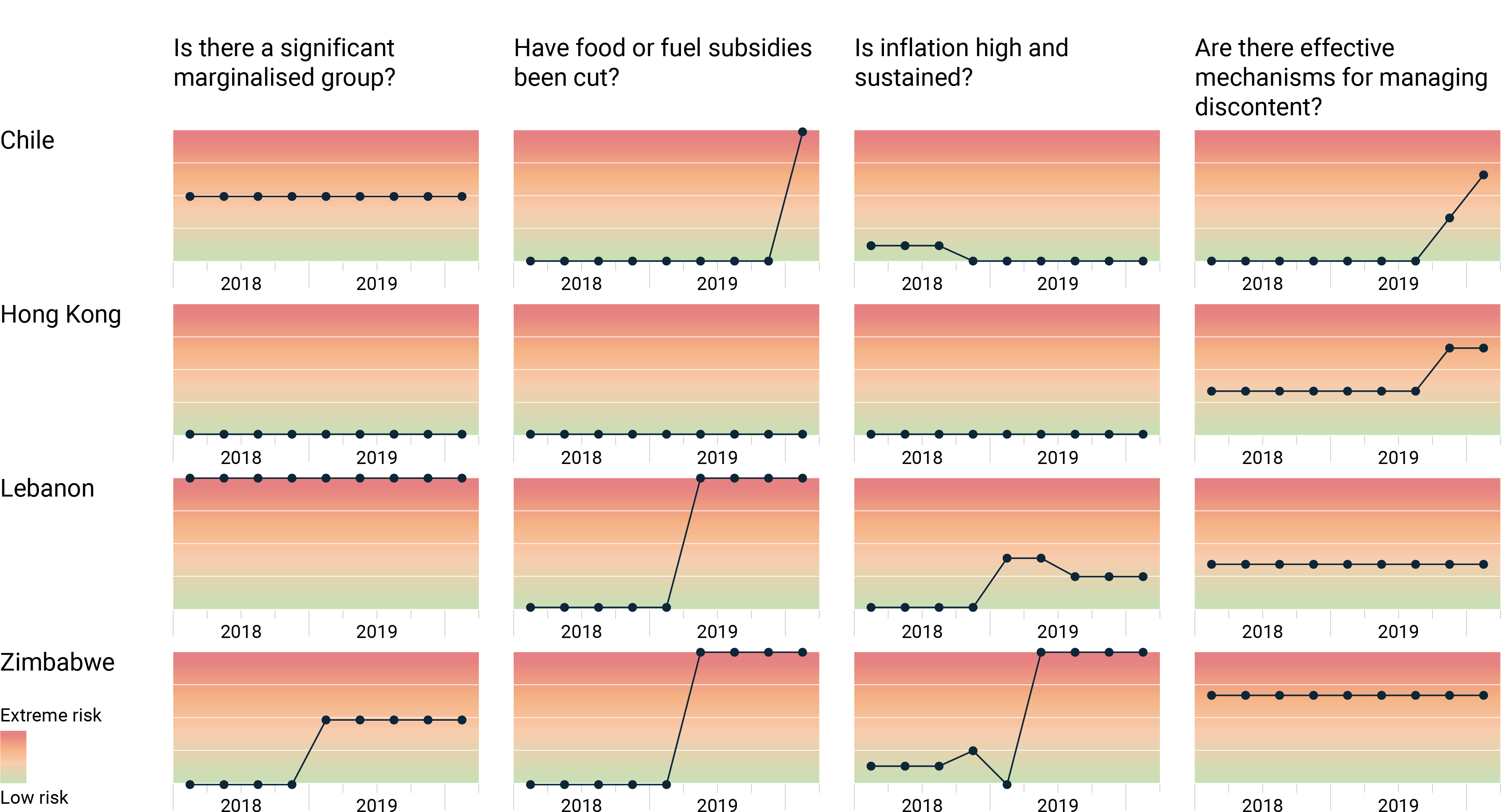

However, an analysis of our data suggests that a deterioration in some risk factors can serve as an early warning sign in certain jurisdictions. Figure 3 shows four out of the 11 indicators that inform our Civil Unrest Index scores. Subsidy cuts were the single biggest indicator that the risk of civil unrest was growing in Chile, Lebanon and Zimbabwe. Inflation and the weakening of mechanisms that allow the channelling of discontent before it erupts into unrest also played a role, the latter particularly in Chile, Hong Kong and Zimbabwe.

Protest-hit countries will see limited improvement, as new jurisdictions likely to join the fray

With protests continuing to rage across the globe, we expect both the intensity of civil unrest, as well as the total number of countries experiencing disruption, to rise over the coming 12 months.

Our baseline forecast for Chile is a minor reduction in unrest over the next six months, while the country will remain in the extreme risk category until at least 2022-Q1 – although the projection allows for some uncertainty (see Figure 4). Our projection means that we do not expect the underlying causes of unrest in Chile to be addressed, even though the demonstrations have succeeded in opening a constitutional revision process, which is set to last from 2020 to 2023.

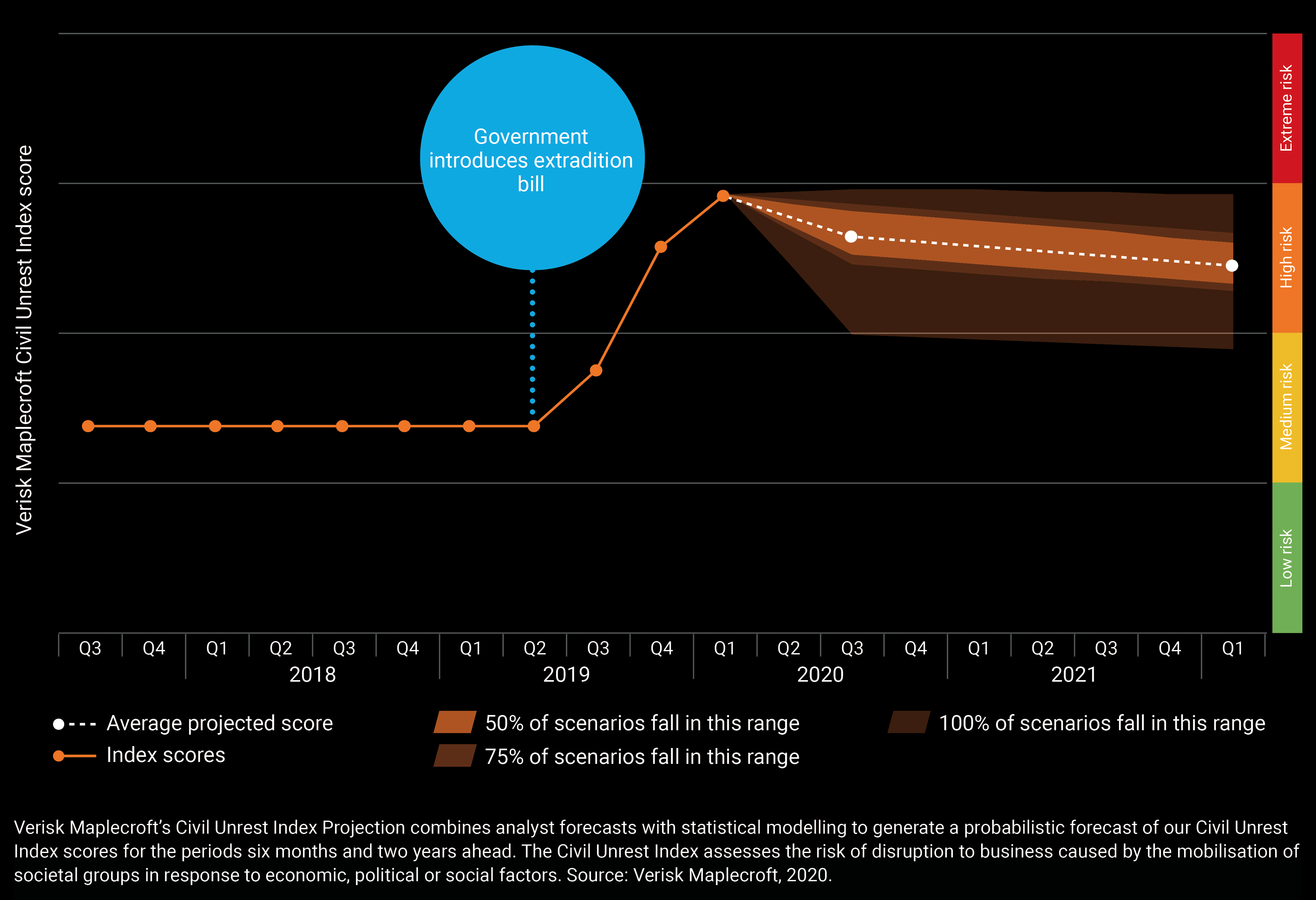

In Hong Kong, divisions between the protesters and the government are now deeply embedded. There is little prospect of a resolution unless the authorities give into protesters’ demands or if Beijing decides to send in the military – both of which are outlier scenarios in our view. According to our projections (see Figure 5), this will most likely mean that protests continue over the next two years, with only minor improvement likely by early 2022.

Where protesters are at highest risk

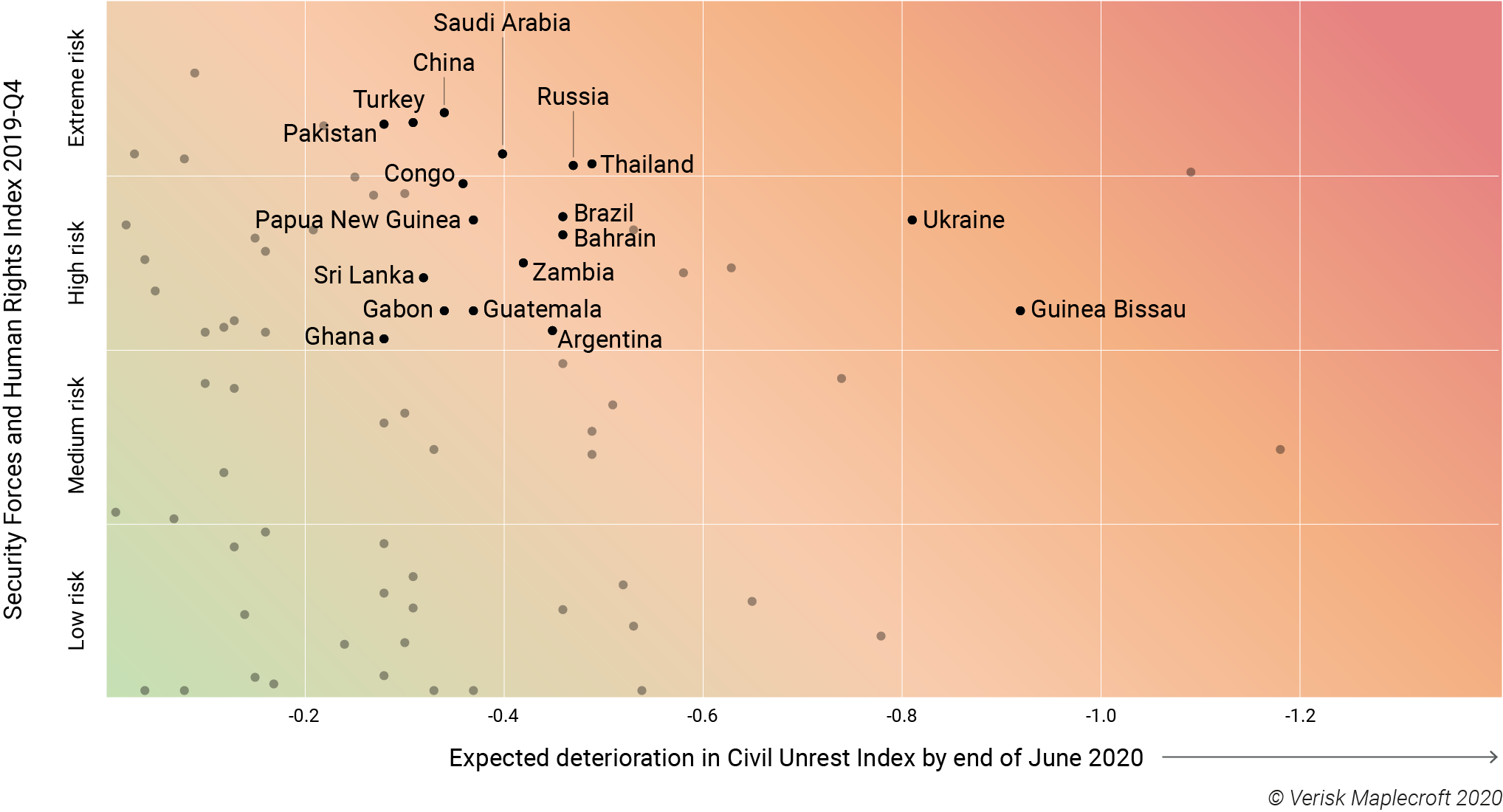

Our projections predict that 75 out of the 125 countries in our forecasting database will on average see an increase in civil unrest during the next six months. A key issue for companies to consider is how these governments will deal with growing unrest (see Figure 6).

Our Security Forces and Human Rights Index, which measures incidents of extrajudicial killings, arbitrary arrest and torture, rates 36 countries as extreme risk on this issue. This includes important emerging markets where security forces have historically responded with heavy-handed tactics, or where they are allowed to commit human rights violations with impunity. These feature mainland China (ranked 9th highest risk), Turkey (11th), Saudi Arabia (23rd), Russia (33rd) and Thailand (30th).

Human rights violations, including arbitrary arrests and the use of indiscriminate violence, pose a risk to protesters and any company staff in the vicinity of ongoing unrest. The use of violence, in turn, radicalises protesters, provokes violent responses and ultimately fuels further unrest.

Register for our Political Risk Outlook 2020 webinar

Businesses operating in emerging economies are often faced with considerable security challenges, particularly in countries rich in natural resources where mining and energy projects often need high levels of protection. However, companies are at substantial danger of complicity if they employ state or private security forces that perpetrate violations. From an investment perspective, the use of state-sanctioned violence is a significant risk to any country’s sovereign environmental, social and governance (ESG) profile, and is no less a risk to the ESG profiles of complicit companies.

2019 likely to be the ‘new normal’

The pent-up rage that has boiled over into street protests over the past year has caught most governments by surprise. Policymakers across the globe have mostly reacted with limited concessions and a clampdown by security forces, but without addressing the underlying causes. However, even if tackled immediately, most of the grievances are deeply entrenched and would take years to address. With this in mind, 2019 is unlikely to be a flash in the pan. The next 12 months are likely to yield more of the same, and companies and investors will have to learn to adapt and live with this ‘new normal’.