101 countries witness rise in civil unrest in last quarter

Worst yet to come as socioeconomic pressure builds

by Torbjorn Soltvedt,

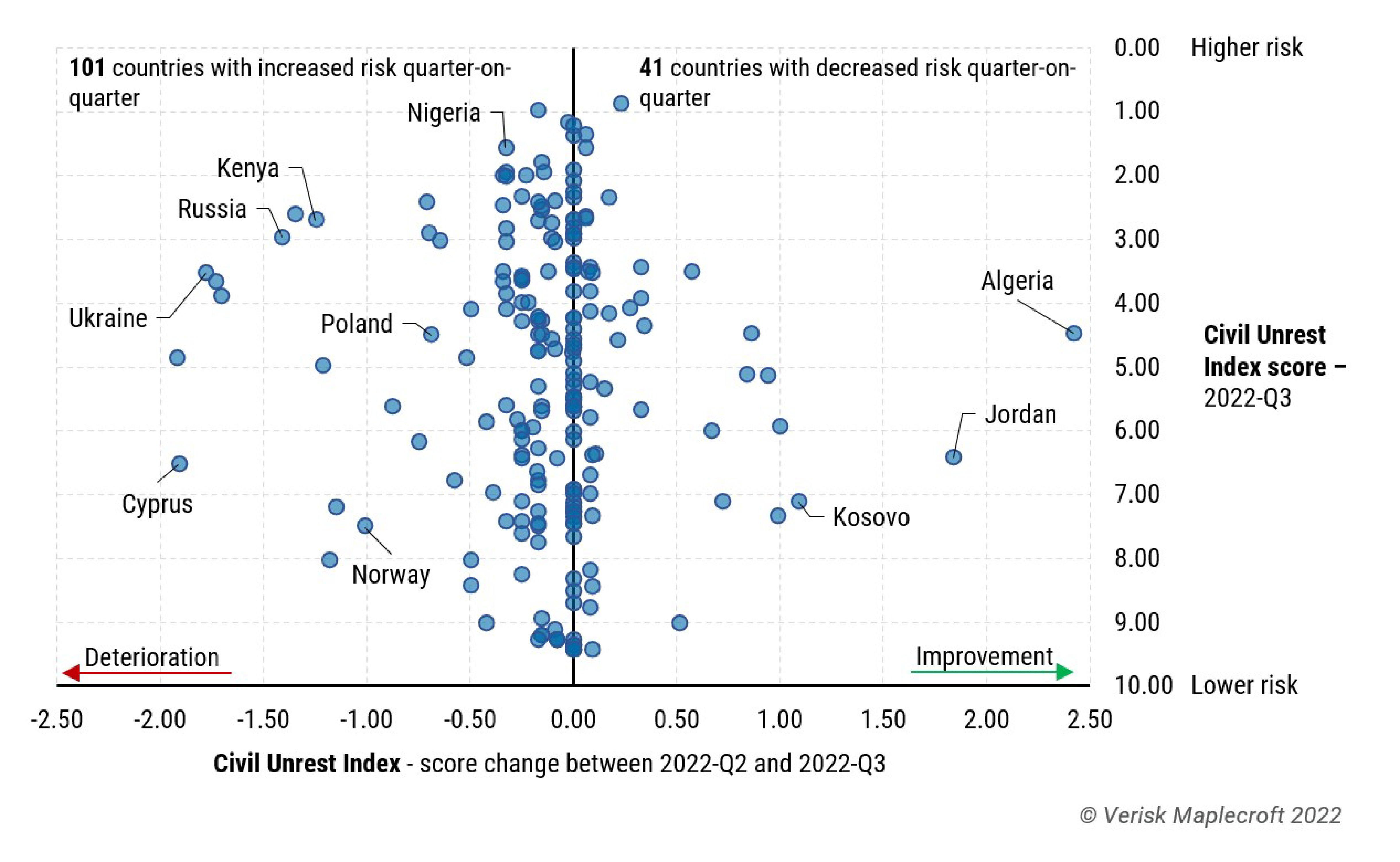

The world is facing an unprecedented rise in civil unrest as governments of all stripes grapple with the impacts of inflation on the price of staple foods and energy, according to the latest edition of our Civil Unrest Index (CUI). The data, covering seven years, shows that the last quarter saw more countries witness an increase in risks from civil unrest than at any time since the Index was released. Out of 198 countries, 101 saw an increase in risk, compared with only 42 where the risk decreased.

The impact is evident across the globe, with popular discontent over rising living costs emerging on the streets of developed and emerging markets alike, stretching from the EU, Sri Lanka and Peru to Kenya, Ecuador and Iran.

As the conditions for civil unrest build in a growing number of countries, the severity and frequency of protests and labour activism is set to accelerate further over the coming months.

Socioeconomic risks rising rapidly

Although there have been several high-profile and large-scale protests during the first half of 2022, the worst is undoubtedly yet to come. In December 2020, we warned of a new era of civil unrest, projecting that 75 countries would see an increase in civil unrest risk by August 2022. The reality has been far worse, with 120 countries witnessing an increase in risk since then.

With more than 80% of countries around the world seeing inflation above 6%, socioeconomic risks are reaching critical levels. Almost half of all the countries on the CUI are now categorised as high- or extreme-risk, and a large number of states are expected to experience a further deterioration over the next six months.

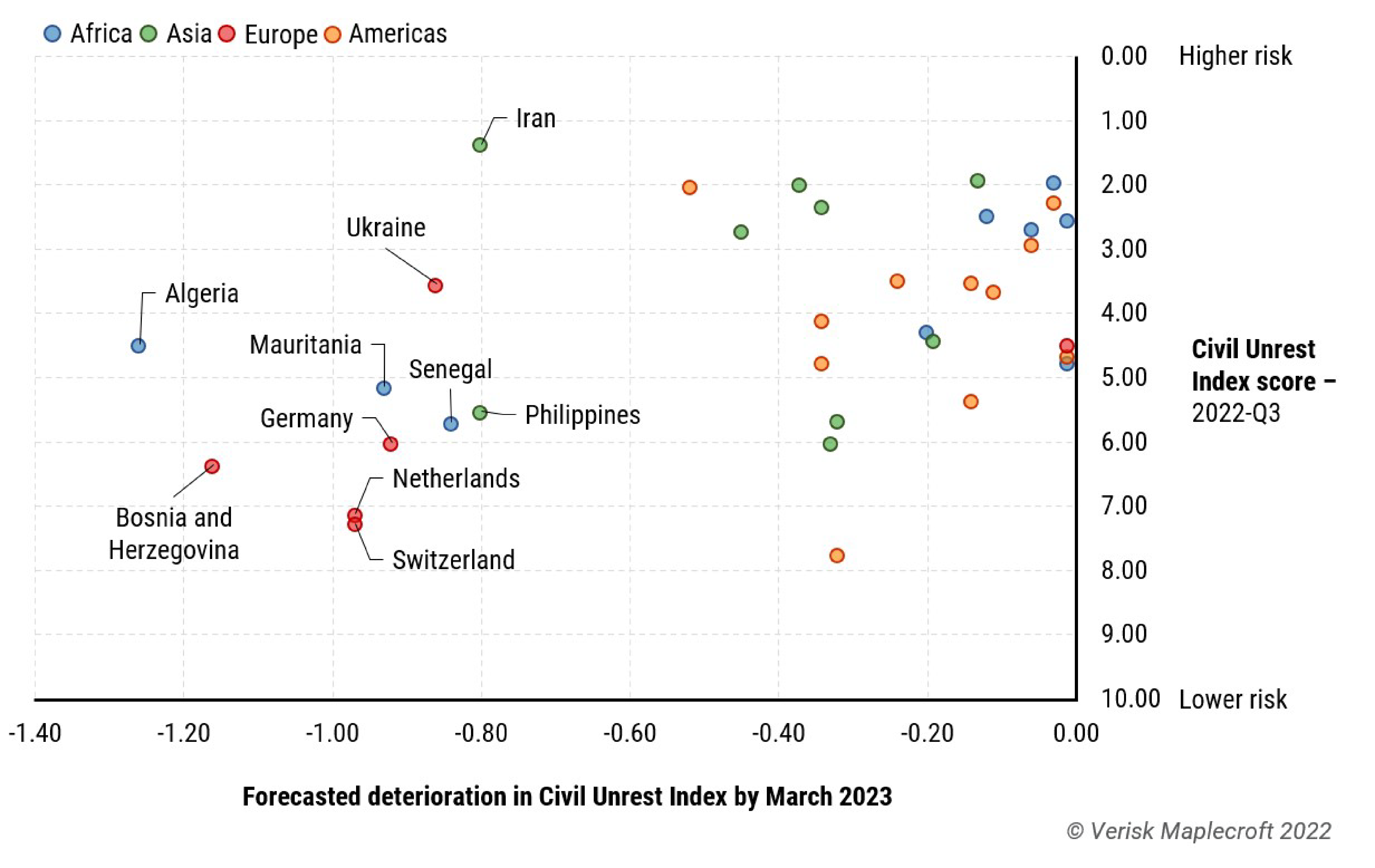

Figure 2 shows the countries where the risk posed by civil unrest is projected to worsen over the next half year. Algeria stands out with the largest projected deterioration, after bucking the global trend in the 2022-Q3 release of the CUI. High hydrocarbons earnings have made it easier to postpone unpopular austerity measures, but rising inflation and more frequent and intense droughts will start to make themselves felt more strongly over the coming months.

Europe also stands out negatively, in large part due to the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Bosnia and Herzegovina, Switzerland, Netherlands, Germany, and Ukraine are all among the states with the biggest projected increases in risk.

Growing number of governments will struggle with rising popular discontent

Over the coming months, governments across the world are about to get an answer to a burning question: will protests sparked by socioeconomic pressure transform into broader and more disruptive anti-government action?

The quarterly trend on our Government Stability Index (GSI) is negative. In the 2022-Q3 release of the index, 42 countries witnessed an increased risk, compared with 27 countries where the risk decreased. Although the negative trend is less marked than for civil unrest, rising food and energy prices will make it more difficult for governments to manage popular discontent.

Unsurprisingly, Sri Lanka experienced the biggest decrease in government stability as protests driven by deteriorating socioeconomic conditions forced the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in July.

As we highlighted in May, middle-income countries that were rich enough to offer social protection during the COVID-19 pandemic, but are struggling to maintain high levels of social spending during 2022, are likely to face the highest risk. It is unsurprising, therefore, that eight out of the 10 largest projected increases in risk on the GSI fall into this category: Bolivia, Egypt, Philippines, Suriname, Serbia, Georgia, Zimbabwe, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

For governments unable to spend their way out of the crisis, repression is likely to be the main response to anti-government protests. Populations in Iran – alongside several other states in the Middle East – are particularly exposed to potential violent responses from security services. What initially started as protests driven by socioeconomic and environmental issues in Iran, for instance, have transformed into protests against the political system, which Tehran has traditionally reacted to with harsh measures. Despite ongoing sporadic protests, government stability in Iran remains in the low-risk category as a result of the state’s significant repressive capacity.

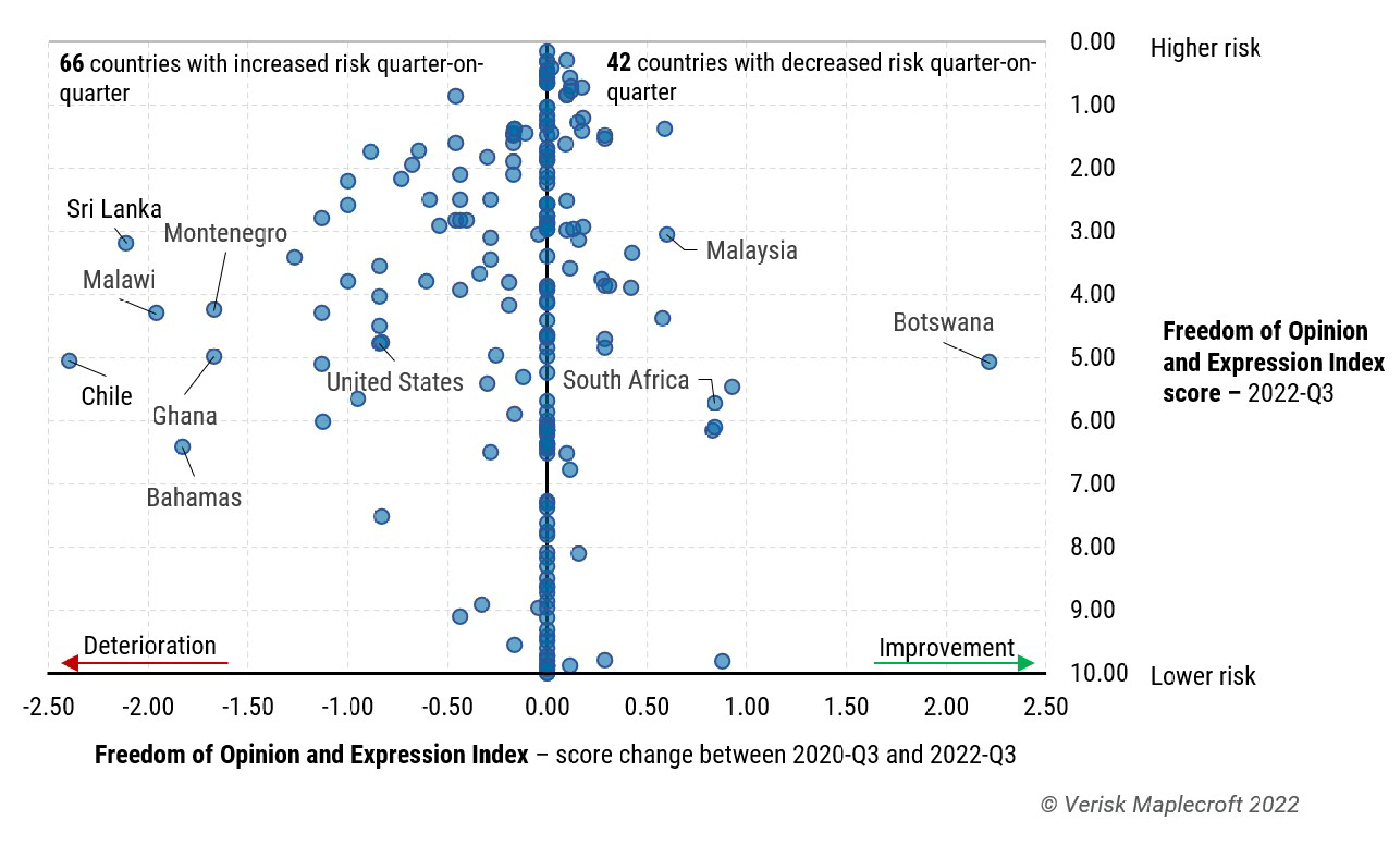

But suppression comes with its own risks, leaving disgruntled populations with fewer mechanisms for channeling their dissent at a time of growing frustration with the status-quo. In countries where there are few effective mechanisms for channeling popular discontent, such as a free media, functioning unions and independent courts, the threshold for populations to take to the streets is likely to come down.

Freedom of speech in Turkey is a case in point, with recent government attempts to criminalise independent economic data that is not approved by the state. This is far from an isolated case though, as underscored by the negative trend on our Freedom of Opinion and Expression Index over the last two years (see Figure 3). During this period, 66 countries witnessed tightening restrictions on freedom of speech. Notably, Chile and Sri Lanka – both of which have been rocked by large-scale civil unrest this year – account for the biggest increase in risk for this issue.

More downside than upside

Only a significant reduction in global food and energy prices can arrest the negative global trend in civil unrest risk. Recession fears are mounting and inflation is expected to be worse in 2023 than in 2022.

Weather will be another crucial factor. A cold autumn and winter in Europe would worsen an already serious energy and cost of living crisis. Similarly, an increase in droughts and water stress globally would worsen already high food prices and spark localised protests in affected areas.

The most explosive civil unrest is likely to occur where avenues for dissent are narrowing and where the ability to shield populations from the rise in living costs are limited. Crucially, this is also where investors are likely to rush for the exit first, leaving the most vulnerable governments even less equipped to take measures to reduce the risk of civil unrest.

Although socioeconomic pressure has already given rise to protests across the world, the next six months are likely to be even more disruptive.