Geospatial ESG investing

Learn more

Rumours of the death of ESG are greatly exaggerated

With oil, gas and coal prices soaring, stagflation simmering, Russia making implicit nuclear threats against the West, and China looming over it all, it feels like the world is stuck in reverse.

Since the start of the year, a slew of commentary has proclaimed the death of ESG investing, proffering data showing negative net flows to ESG funds for the first time since 2020.

Yet, developments in the past week also give cause for a more nuanced view. The arguments calling for more fracking, more coal and more gas in the name of US and European energy security don’t stack up – or at least not for very long.

The fact is that the global economy is now in the throes of a transition period that the pandemic, and the latest crisis in Russia-Ukraine, has made more urgent, and more difficult. The latest IPPC report on Climate Change reinforces that, with Brian O’Neill, one of the authors of the report’s chapter on future risks, noting that regions ‘awash with nationalism and military conflict, or racked with poverty and inequality’, is a big problem to how the world will look under accelerating global warming.

Europe was already enduring its first ‘net zero’ crisis before the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Anyone paying any attention has understood that this transition was going to be extremely complex and – for consumers and industry alike – expensive and unsettling. Structural change is hard.

But few politicians would ever admit to that, or take the difficult decisions required to wean economies off their addiction to - and permanent expectation of – cheap fuel.

Election cycles – not Russian aggression – have been the bigger threat to the net zero transition. Until now.

In Europe at least, the Ukraine crisis is giving fresh momentum to Sovereign ESG considerations. Led by Germany, the EU appears to be reviewing its strategic decision as to the role of gas in the bloc’s path to net zero (whether Russian or other supply).

The case for renewables, as well as alternative gases such as bio-methane and green hydrogen, is now looking stronger, not weaker on all metrics; environment, economic, social and security. As our colleagues over at Wood MacKenzie note, while these will take time to develop at scale (scale being critical to reliability), they will, over time, diminish the role of natural gas in the energy transition in Europe and beyond. On this reading, the E of the environmental agenda is very closely aligned to the S of the security agenda.

And what of the S and the G? Does the new ‘Cold war’, the rise of China and the global crisis in democracy put paid to these?

The overwhelming international response to the Ukraine crisis suggests not. European governments appear to have rediscovered their moral compass over the weekend.

The Western corporate response to the crisis is a key indicator. The hasty exit of energy giants BP and Equinor from Russia may be the prelude to a stampede by nervous investors, not only under intensifying international legal pressure, but also under shareholder and reputational pressure.

And as our Europe team notes, Russia’s aggression has prompted Eastern European states to turn back towards the West – with Bulgarian and Czech Republic voters in 2021 abandoning radical nationalist populists in favour of more conventional social-democratic political parties, a trend we expect to continue in 2022, with elections in Hungary, Slovenia, Latvia and Bosnia & Herzegovina.

Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia and Slovakia have all seen their performance deteriorate on our Democratic Governance and/or Judicial Independence indices since 2017.

As these countries seek the protection of the EU and NATO, governments will be required to respond in kind, with improvements to the rule of law, democratic governance, political, civil and social rights.

Some of the democratic and social backsliding seen in countries such as Poland in recent years may thus be slowed or reversed.

And furthermore, in an effort to more closely align themselves with the EU, the current crisis is also likely to speed up the energy transition of Eastern EU states that have lagged behind their Western neighbours.

But there is a bigger immediate test of the ‘S’ across Europe.

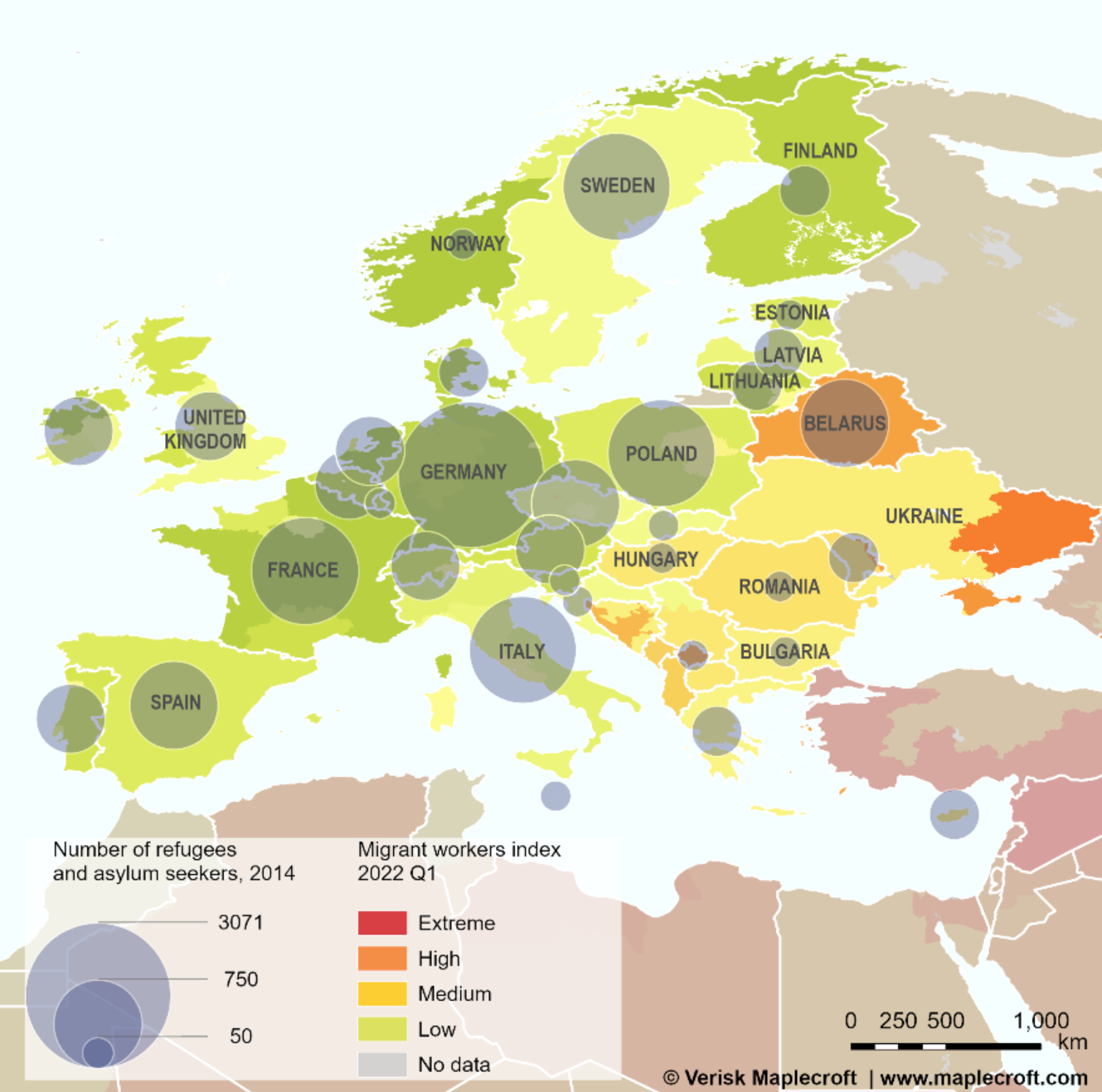

Preparations are underway across the EU to accommodate the wave of Ukrainian refugees expected to seek asylum in the bloc. Patterns observed following the annexation of Crimea suggest that France, Germany, Italy and countries neighbouring Ukraine – particularly Poland – will bear the brunt of the influx.

Most of these countries score medium risk on our Migrant Workers Index, suggesting that a refugee upsurge will increase human rights risks for companies operating in these countries.

The prospect of a refugee crisis is a potential boon for right-wing anti-immigration parties. Ahead of elections in April, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán has already woven the scenario of a migrant crisis into his political campaign. Likewise, France’s Eric Zemmour’s ‘Immigration Zero’ campaign.

Eileen Gavin

Principal Analyst, Global Markets & Americas

ESG+ Matters notification

SubscribeChart of the week

Quote of the week

I am here. We are not putting down arms. We will be defending our country, because our weapon is truth, and our truth is that this is our land, our country, our children, and we will defend all of this.

Volodymyr Zelensky

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky

What we’re reading

- Vladimir Putin’s nuclear threat shows how much is going wrong for him in Ukraine, The Economist, 28 February 2022

- Global warming is outrunning efforts to protect human life, scientists warn, Bloomberg Green, 28 February 2022

- Climate Change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, IPCC WGII Sixth Assessment Report, IPCC 28 February 2022.