Threats to food security increase in 135 countries – Europe registers largest uptick in risk

The Trendline

by Jess Middleton,

Threats to food security are rising globally as governments grapple with the fallout from fluctuating commodity prices amid a cost of living crisis and increased economic, geopolitical and environmental volatility, according to our latest research.

Our Food Security Index (FSI), which evaluates the availability, access and stability of food supplies in 186 countries, shows that 135 countries have seen an increase in risk since 2022-Q4, compared to 48 where the risk decreased. Only 13 countries fall within the low risk category of the latest edition of the FSI, the lowest number since the dataset launched in 2017.

Risks continue to run highest in parts of the developing world, with countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas most at risk. But the data – which also considers nutritional outcomes for each country’s population - highlights rising food insecurity even among rich nations, with Europe witnessing the largest increase in risk of any region. The likes of Australia, New Zealand and Canada have also seen an uptick.

Figure 1: Food security risks have increased in most countries

“Elevated food insecurity risks can trigger a domino effect, disrupting agricultural, transportation and distribution networks, in turn fostering input cost volatility and constraining profit margins,” says our Chief Analyst Jimena Blanco. “Diminished consumer purchasing power alters consumption patterns and amplifies economic uncertainty, with these interlinked dynamics posing formidable challenges for businesses with exposure to the food industry.”

Sub-Saharan Africa most at risk from food insecurity

While the data shows that food insecurity is a growing issue the world over, the findings are especially significant for countries in the developing world, where poverty, conflict and poor governance can combine to create conditions where food crises may take hold.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Yemen (ranked 1st and highest risk) and Somalia (ranked 2nd), where sustained violence and ineffective governance have triggered mass displacement and tipped millions towards hunger. Similar themes have impacted food security in Central African Republic, Afghanistan and Haiti, which round off the list of five highest risk countries globally.

Zooming out shows that 16 of the 20 countries rated very high risk on the index are in sub-Saharan Africa, which remains the least food secure region globally for a seventh consecutive year.

Figure 2: 20 countries rated very high risk for food insecurity

Geopolitical and environmental volatility compound threats to food supply chains

Elsewhere, the availability of essential foods has been impacted by disruptions to agricultural trade flows linked to conflict in Europe and the Middle East.

Indeed, the war in Ukraine continues to have an impact on global supplies of wheat, barley and sunflower oil, of which the warring powers are both major exporters, while the maritime security crisis in the Red Sea has caused uncertainty for food shipments using the Suez Canal.

At the same time, these risks have been exacerbated by the impacts of extreme weather, with poor harvests prompting major agricultural producers to impose export bans on staple crops such as rice and onions.

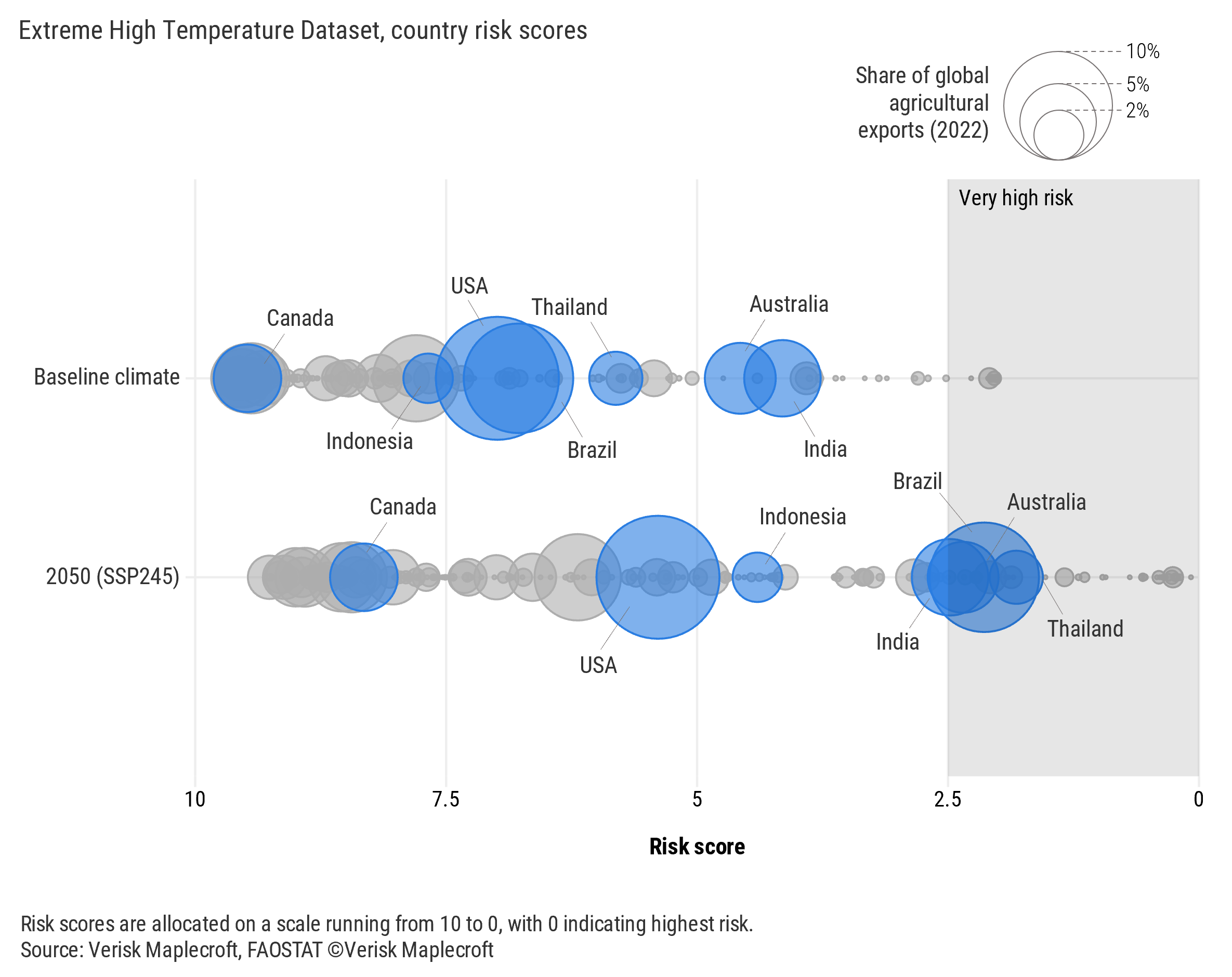

But our data shows that climate-driven disruptions to food supplies are only set to grow more common in the coming years. For example, data from our Extreme High Temperature Dataset shows that 11 countries are rated very high risk for the issue in the current climate. That number could rise to 40 by 2050, according to our data covering an intermediate emissions scenario, threatening agricultural outputs in countries that currently account for 25% of the world’s food exports. Major breadbasket nations, including Brazil, India and Australia, are among those facing the highest risk.

Developed world not immune

While the immediate impacts of rising food insecurity will be felt most acutely by poorer populations in developing countries, the secondary impacts have the potential to cascade across national borders.

Civil unrest and government instability linked to reduced access to food can disrupt business operations and undermine investment returns for multinational organisations, while increased migration could stoke populist rhetoric in destinations such as the United States and the EU.

However, data from the FSI shows that richer countries are also contending with rising food insecurity closer to home. Indeed, risks increased in 35 of the 38 OECD member countries on the latest edition of the index, driven by rising living costs, increased political instability and a high dependence on food imports. The average risk for the cohort is at its highest level since 2017.

As in the developing world, the most vulnerable members of these societies face the greatest risks. In Britain (ranked 160th on the index), the number of children living in food poverty almost doubled to 4 million between 2022 and 2023. In Australia, which remains the 2nd lowest risk country on the FSI despite registering a significant increase in risk, 3.7m households experienced food insecurity in the 12-months prior to October 2023, up around 350,000 from the previous year.

Rising food insecurity to act as risk multiplier

As rising economic, geopolitical and environmental threats combine to impact the stability of global food supplies, businesses need to stay alert to emerging direct and indirect risks, which have the potential to amplify social tensions, disrupt operations and destabilise investment environments in key markets around the world.

“Food insecurity is a critical risk multiplier that can impact supply chains, alter consumption patterns and stoke social unrest and political instability,” adds Blanco. “At the same time, food scarcity can hinder human capital development, undermining both present and future socioeconomic resilience.”