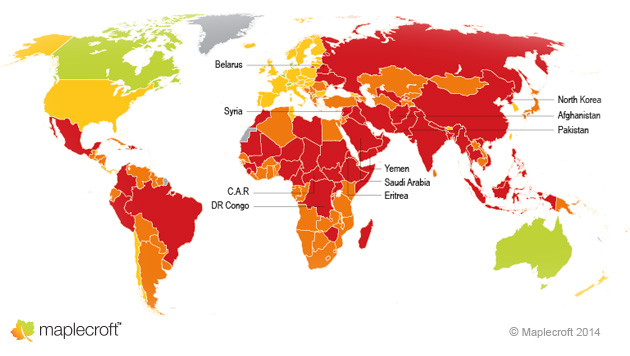

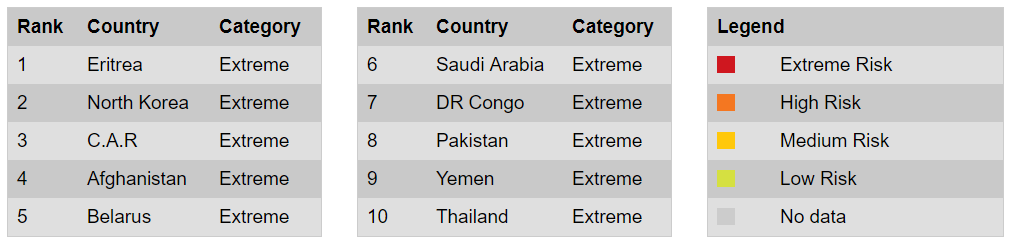

Human rights deteriorating in Ukraine, Thailand, Turkey, due to repression of civil unrest

Risk Atlas 2015

Over 2014, the human rights situation has deteriorated most in Ukraine, Thailand and Turkey due to heavy-handed government responses to civil unrest and failures in rule of law, according to our tenth annual Human Rights Risk Atlas (HRRA), which also reveals increasing polarisation between the world’s best and worst performing countries. Sharp deteriorations have also been recorded in Equatorial Guinea, CAR and Djibouti.

Our analysis indicates that the increase in the countries at opposite ends of the risk spectrum reflects an increasing divergence in human rights protection globally. Government repression, especially violations committed by state security forces against opposition groups and protesters, are a key reason for the increase in ‘extreme risk’ countries, while robust governance, progressive reforms and active civil society have fostered improvements in ‘low risk’ countries.

Ukraine, Thailand and Turkey experience steepest declines in respect of human rights

The HRRA, which ranks 198 countries on their performance across 38 violation categories, has been developed to assess the reputational and operational risks to global companies, especially those operating in the emerging markets. While the majority of these key investment destinations have not improved over the past year, we identify Thailand (ranks 34th most at risk) and Turkey (69) as experiencing among the world’s steepest declines for the protection of human rights. In both countries, which slipped 14 and 9 places in the rankings respectively, increasing violations have been recorded in the wake of widespread civil unrest.

For the first time in ten years, Thailand (34) has been downgraded to an ‘extreme risk’ country. We attribute violations committed by state security forces against opposition groups following the May 2014 military coup as a key driver of Thailand’s downgraded position. The political transition has also prevented the implementation of necessary regulatory reforms to address abuses against migrant labourers and the country continues to be a hub of forced labour violations. The fishing industry remains a sector of concern, but we also identify manufacturing as an industry where companies are at risk of being complicit in labour abuses.

In Turkey, repression of civil and political rights, especially freedom of speech and the media, as well as violations against demonstrators committed by security forces during country-wide protests, are a key reason contributing to the country’s fall in the HRRA. We assert that when widespread human rights violations, such as these, are present in a country they have the potential to trigger further unrest and spur greater political risks to investors, particularly in respect of societally induced regime change.

Nowhere is this more true than in Ukraine (44th most at risk), which fell 19 places in the overall HRRA ranking, and this year experienced the greatest annual increase in human rights risks in the world. In addition to the current conflict, the decline reflects an ongoing deterioration of human rights protections since 2011. Ultimately, the worsening human rights situation in Ukraine created the conditions for popular discontent that resulted in the ousting of President Viktor Yanukovych.

Conflict-driven forced displacement fuels trafficking and modern slavery risks

While the new government in Kiev is working to improve its protection of human rights, Russian authorities in Crimea and separatist forces controlling Donetsk and Luhansk are engaged in routine kidnapping, torture and summary executions. The HRRA identifies exploitation of over 430,000 conflict-driven migrants as a serious issue, with Ukraine slipping from 29th most at risk to 19th in the HRRA’s Forced Labour Index and from 39th to 31st in the Trafficking Index.

“Displaced populations, especially women and children, are exceptionally vulnerable to exploitation through trafficking and modern slavery,” states Lizabeth Campbell. “Aside from the obvious humanitarian tragedy, the displacement of these vulnerable groups carries significant risks for companies, as victims can appear in various stages of company supply chains, particularly in sectors such as manufacturing, agriculture and mining.”

In the last year, ethnic and sectarian conflicts have been a key driver in the increase of displaced persons. This has led to an intensification of human rights and labour rights abuses in a number of the worst performing countries in the HRRA, including: Syria (1), Sudan (2), Iraq (3), Somalia (4), Afghanistan(5), DR Congo (6), Pakistan (7), Central African Republic (8), Nigeria (9) and South Sudan (10).

Despite the increasing risks of modern slavery and trafficking created by conflict, our research reveals that these issues are not by any means confined to war-torn or unstable countries. The HRRA categorises 49 countries as ‘extreme risk’ in the Forced Labour Index, which features many of the world’s emerging economies. These include China, India, Mexico, Thailand, Indonesia, Colombia, Vietnam, Bangladesh and the Philippines, where companies remain highly exposed to labour related violations despite high levels of economic growth.

In addition, developed economies are not immune to trafficking and slavery risk. The United Kingdom in particular has taken steps to combat forced labour in supply chains through legislative efforts such as the Modern Slavery Bill. If passed, the bill would require businesses to report efforts towards eradicating modern slavery from their supply chains, including enhanced human rights due diligence and supplier monitoring procedures.

West Africa makes greatest headway

Regionally, West Africa demonstrates the greatest improvement in its human rights risk environment. Cote d’Ivoire(improved from 33rd last year’s HRRA to 48th), Senegal (68th to 84th), Togo (81st to 94th) and Liberia (90th to 99th) have all shown significant progress in the past year due to constitutional reforms – resulting in better governance, increased public participation in the political process and sustainable economic opportunities.

“This is the tenth Human Rights Risk Atlas and the rich content allows analysis of trends over the decade and enables companies to monitor the trajectories of the countries where they operate,” states Alyson Warhurst. “Not only are human rights due diligence and monitoring the right things for companies to do but they can help business to assess risk of complicity and a downturn in the stability of the business environment.”

Human Rights Risk Atlas 2015

Our Human Rights Risk Atlas 2015 is designed to help business, investors and international organisations assess, compare and monitor human rights risks and trends across all countries over seven years. The Atlas includes interactive maps and indices for 38 human rights categories and scorecards for 198 countries covering human security, labour rights and protection, civil and political rights and access to remedy. It also features sub-national mapping of human rights violations and human security incidents down to site-specific levels worldwide.