President Joe Biden has prioritised climate change in his first months in charge. Most notably, he rejoined the Paris Agreement 107 days after Donald Trump officially exited. And, domestically, a January executive order outlined a host of measures including doubling offshore wind-produced energy by 2030, pausing new oil and gas developments on federal lands, and directing federal agencies to prepare for the impact of climate change on their operations.

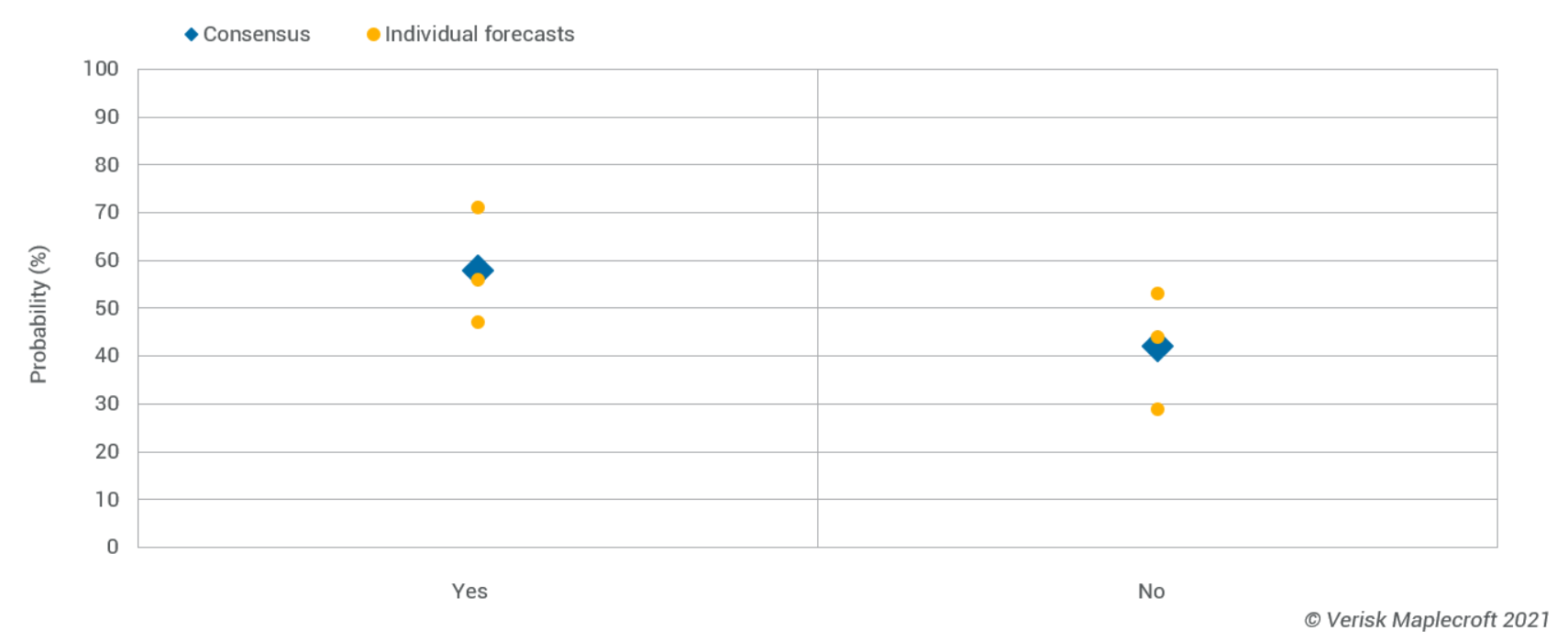

Biden spoke about mandating public companies to consider climate risks on their strategies and operations and to disclose those threats on the campaign trail. But while we are yet to see movement on that front, our forecast team believes he will make good on his promise: we put the chance of regulations coming in by next year at 58%.

Moving the needle

Businesses across the economy face significant risks from climate change, both in terms of increasing physical threats from issues like storms, droughts, and rising sea levels, but also transition risks arising from stricter carbon mitigation policies. Improving climate disclosures enables investors to better allocate capital and enhances corporate focus on the risks - and opportunities - climate change will bring about. Conversely, failure to meet investor demands can threaten a company's ability to raise finance while leaving it vulnerable to physical climate threats, slow to capitalise on opportunities, and potentially exposed to punitive action from regulators.

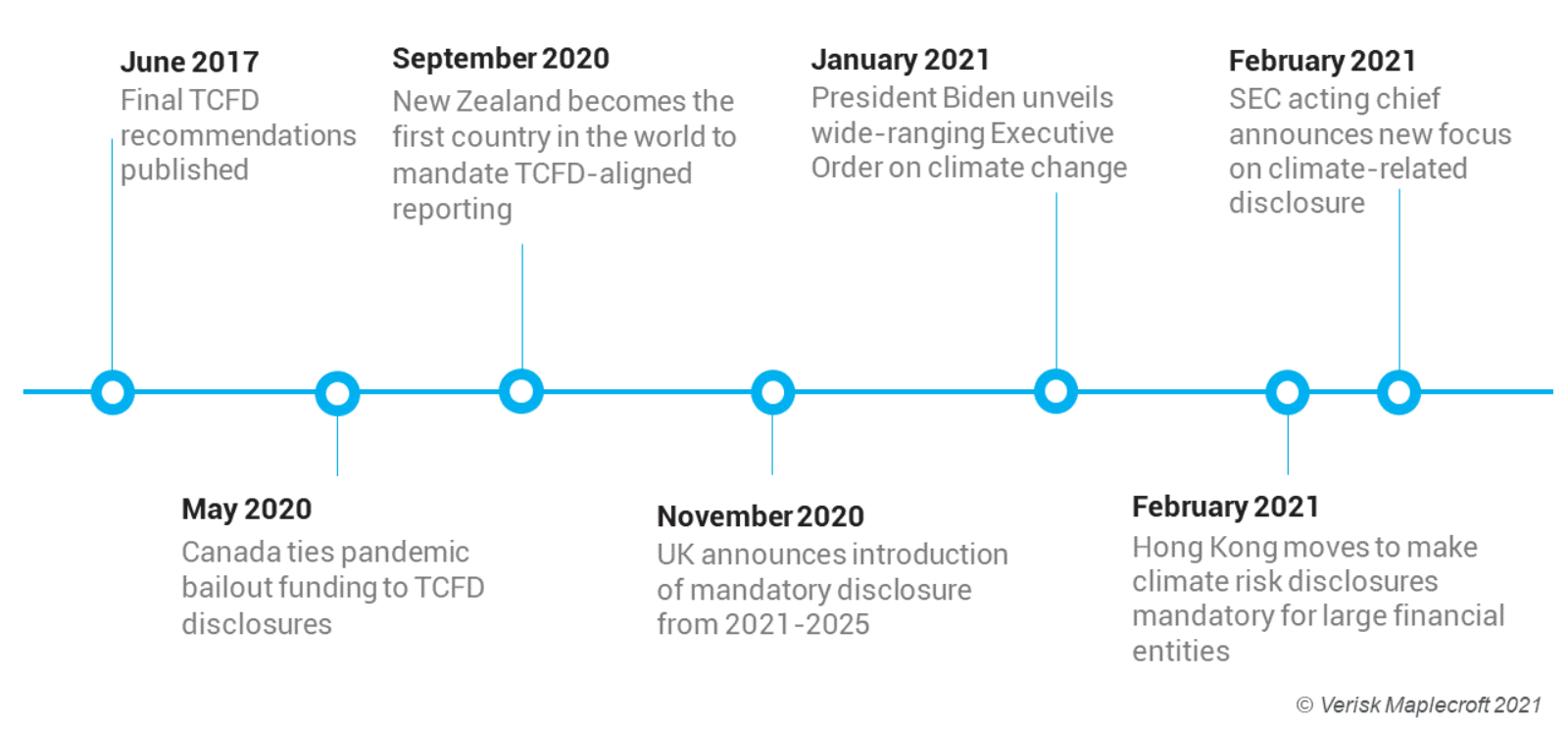

The advent of the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) has provided a unifying framework to identify, manage, and detail those risks and opportunities around which other disclosure benchmarks are coalescing.

Learn more about sustainability reporting and disclosure

Uptake has been steady since the recommendations were launched in 2017: the TCFD's 2020 progress report found nearly 60% of the world’s 100 largest public companies support the TCFD, report in line with the TCFD recommendations, or both. However, it also shows that North American companies as a whole are lagging behind their European and Asia-Pacific counterparts in terms of TCFD-aligned disclosures.

Certainly, there is pressure from investors to close that gap. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink has backed calls for broader climate risk reporting and has asked companies to align with TCFDs. Others will surely follow the world’s largest asset manager. Meanwhile, activist investor groups like Climate Action 100+ are increasingly high-profile: this proxy season, the group has filed 37 shareholder proposals at North American focused companies, including ExxonMobil, General Motors and Phillips, demanding enhanced climate risk disclosures and alignment with the Paris Agreement.

Regulators starting to step in

On top of investor pressure, there are clear signs from regulators that the TCFD framework may not remain voluntary for very long. In the UK, large pension fund and financial institutions will need to align with the TCFD recommendations by the end of this year, with economy-wide, mandatory climate-risk disclosure rules expected to be in place by 2025. New Zealand has slated rules to be implemented in 2023, Hong Kong is pushing sweeping climate disclosure regulations, while the EU's Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation and taxonomy bring the prospect of mandatory reporting closer than ever before. Even in lagging North America, Canada tied pandemic bailout funding to TCFD-aligned disclosures, indicating a direction of travel.

Invariably, these rules fall on the financial sector first, with a view to cascading requirements throughout the economy. We would expect US implementation to follow suit, which would swiftly lead to pressure on oil and gas, mining, transport, agri-business and other sectors heavily impacted by physical and transition climate risks.

Political barriers remain

Historically, the US has not been at the forefront of climate action - a situation compounded by four years of the Trump administration. Climate policy is politically contentious in a way that is only really replicated in Australia. Given Republican distrust of any action on climate, a finely balanced Senate leaves the Democrats needing to convince the moderate wing of their own party, such as West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed a 2010 climate bill.

As such, Congressional approval is an unlikely route for climate risk reporting to successfully traverse. An executive order is plausible, but could easily be undone by a future administration. Perhaps the more likely method is in concert with financial regulators such as the SEC, which has been ramping up its involvement in climate risk concurrently with the Federal Reserve.

Explore our climate change and environment offerings

The SEC already requires public corporations to disclose material information on financial health and exposure to risk and clarified in 2010 that these rules apply to climate risk. To date it has not pushed on climate, but Acting Chair Allison Herren Lee issued a strong statement on February 24 saying the regulator would bolster its focus on how companies are responding to that guidance as another step "on the path to developing a more comprehensive framework that produces consistent, comparable, and reliable climate-related disclosures".

The creation of a new senior position on ESG and climate and a general thawing towards ESG considerations has also raised expectations climate risk will become more central in the regulator's thinking. At the same time, the Fed has become more outspoken on climate, while forming a new panel looking at climate implications for "financial institutions, infrastructure, and markets" and a new Supervision Climate Committee (SCC) to analyse climate risk. In December 2020, the Fed also joined the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System.

So the SEC certainly has the power to introduce climate risk reporting and increasingly seems to have the motivation. Our forecast team will continue to follow the issue over the coming year.