On 1 February, the Myanmar military seized power from Aung San Suu Kyi’s government and declared a one-year state of emergency after detaining her as well as key officials. The coup is a devastating setback for the country’s democratic development after years of efforts to shake off the impacts of decades of military rule.

The military, led by General Min Aung Hlaing, tried to justify the takeover by delegitimising a general election in November 2020, in which Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy (NLD) won by a landslide. But on Wednesday, the Biden administration designated the military takeover a coup and threatened to re-impose sanctions on Myanmar's generals. China, by contrast, did not join the condemnation and called on all sides to respect the constitution.

Find out more about our Country Risk Intelligence

Turning back the clock on business investment?

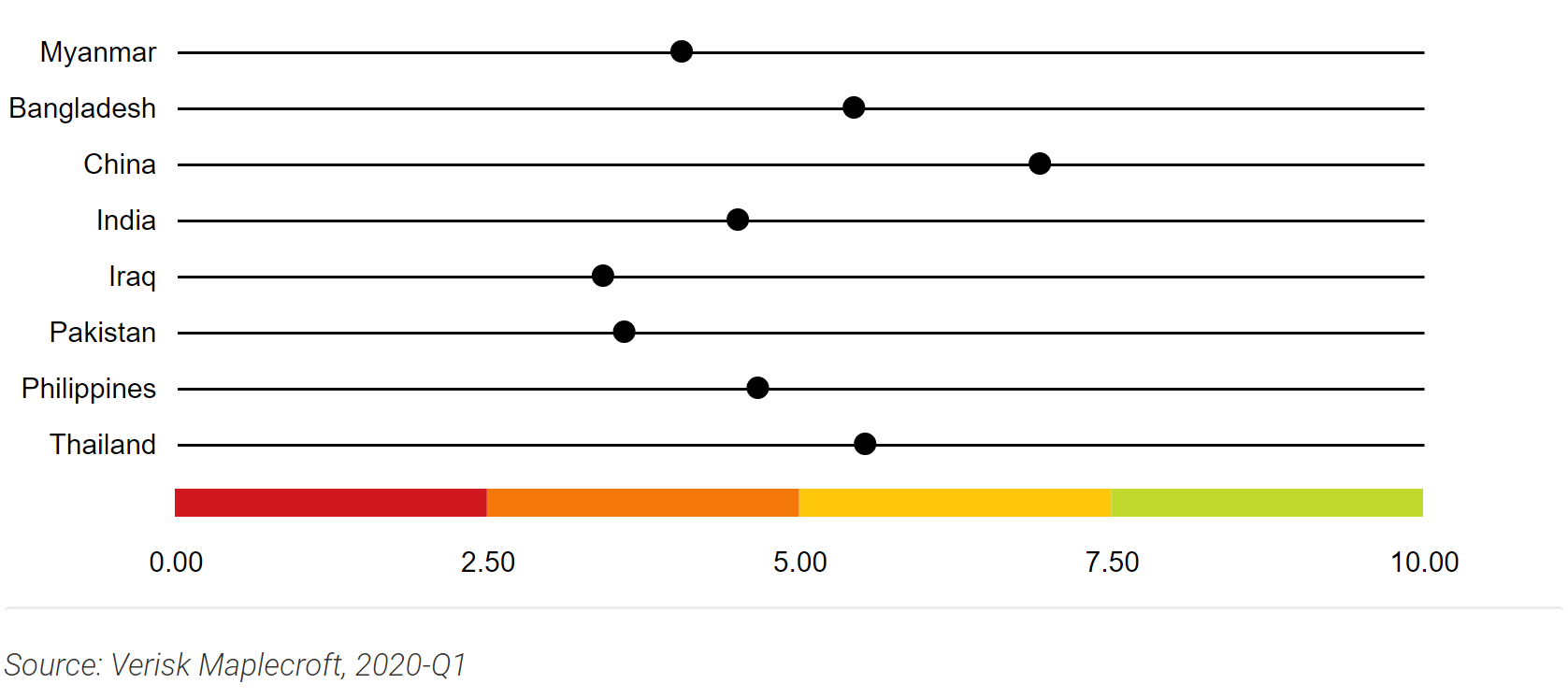

The one-year state of emergency declared by the military has created significant uncertainties for the business environment. Myanmar ranks as the 14th highest risk country globally in our Political Risk Index 2021-Q1. The index assesses the key regulatory, political violence, transfer and convertibility, and government stability risks shaping the strategic and operational landscape for business.

Foreign companies had hoped the end of military rule in 2011 would improve the business environment in one of Asia's key resource-rich markets, but we expect the coup to damage Myanmar's economic recovery plans and erase foreign investor interest. Alongside the Rohingya crisis and a troubling human rights record, safety concerns and political uncertainties in the wake of the coup will likely prompt some foreign companies in Myanmar to halt operations or pull out from the country entirely.

Although upstream fields in Myanmar will likely maintain production levels despite the coup, we expect the political uncertainty to derail new investment plans. Given the importance of new upstream development to the country’s economic recovery, we expect the military to try to reassure foreign investors that the country will be back business as usual soon. Yet, under the current circumstances, it will be difficult for Myanmar to carry out energy reform or to revise its fiscal terms to attract upstream investors.

ESG risks deepen for foreign investors

Moreover, the military will likely undo some NLD policies that have acted as a starting point for improving transparency and fairness in Myanmar's business environment, such as carrying out stricter scrutiny policy for inward investment. Unclear standards and weak enforcement are key challenges for businesses in Myanmar, and rolling back reforms will worsen already-significant ESG risks for foreign investors. For example, Myanmar is already ranked as the 5th highest risk country globally in our Strength of Auditing and Reporting Standards Index for 2021-Q1.

We expect the US to restrict foreign assistance to Myanmar and impose new sanctions on those involved in the coup, particularly military officials and associated entities. Yet, additional sanctions will likely have limited impact because many relevant individuals and entities were already sanctioned by the Trump administration in 2019 over the Rohingya crisis. Instead, any new sanctions would make it harder for responsible companies adhering to international best practice to keep operating in Myanmar due to reputational and ESG considerations.

Learn more about how we can help you with ESG risk

The military has long been active in Myanmar's economy via its two holding companies, the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited and Myanmar Economic Corporation. Its widespread influence across most sectors of the economy, from natural resources to retail, will continue to limit democratic development. The military's continued influence means foreign businesses will have no choice but to work with military-affiliated local partners, which is likely to eventually expose them to reputational risks or even sanctions.

Coup plays into China’s hands

China's response to the coup so far reflects that it is taking a ‘wait and see’ approach. Beijing has adopted a pragmatic approach towards Myanmar for decades and has been engaging both with the military and the Aung San Suu Kyi-led government. For Beijing, it does not matter who rules Myanmar, as long as those in power are not anti-China.

Any tough counter-measures from the US, such as sanctions, would drive Myanmar ever closer to China. Once the political turmoil settles down, we expect China to resume efforts to integrate Myanmar into its economic orbit. The current political uncertainty will certainly lead to business disruption, but we expect Myanmar to remain a long-term destination for Chinese investment, particularly in the energy, mining and infrastructure sectors.

Civil unrest ahead

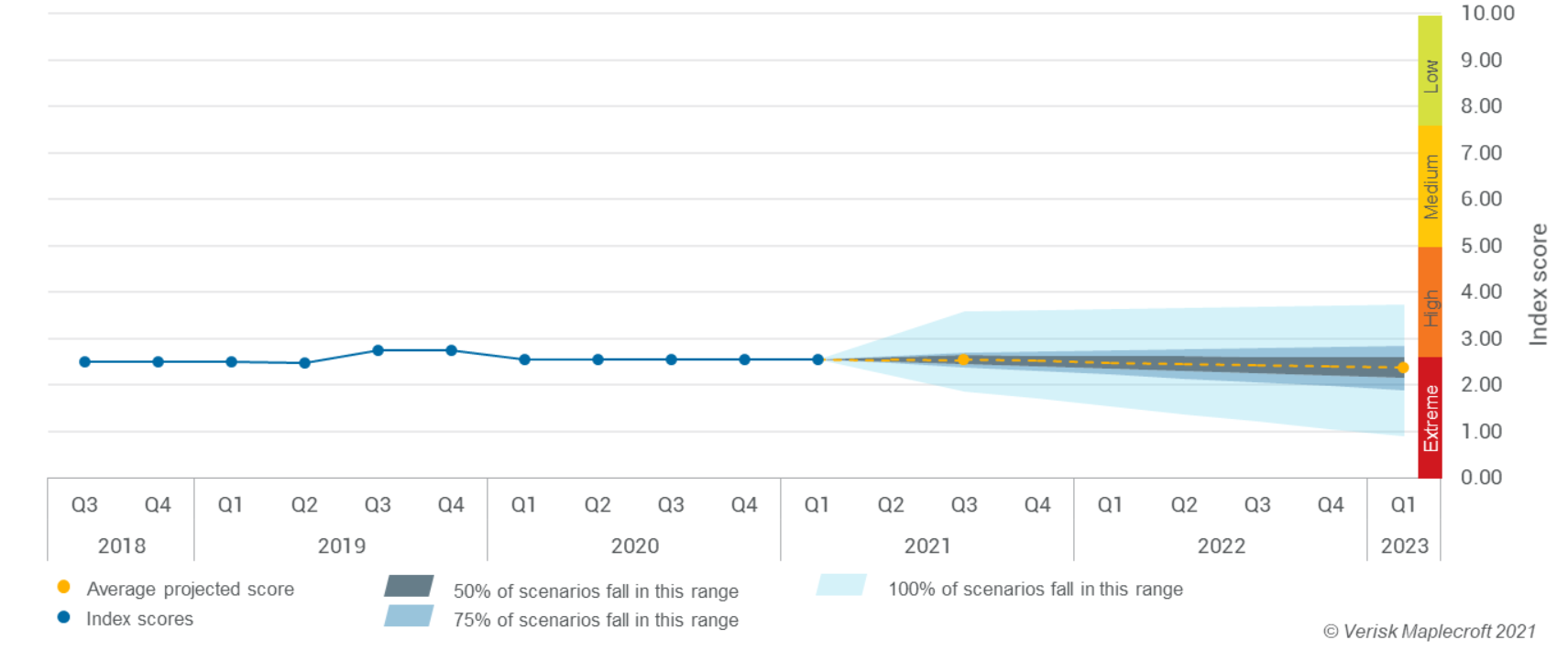

The coup will also likely increase the risk of civil unrest in Myanmar. Our pre-coup Civil Unrest projections already indicated that the country will remain in the high-risk category for the next two years (see figure below), and we expect future updates to reflect an even higher risk of protests. As a sign of things to come, the Yangon Youth Network activist group launched a civil disobedience campaign against the coup on 2 February.

We expect limited room for negotiation between the military and the NLD in coming months. Similarly, the coup will likely intensify existing tensions between the central government and ethnic armed groups, signalling a halt to the long-running peacemaking process.