Species loss is not a new problem, but regulators, investors and consumers are increasingly alarmed at the rate of destruction: around one million animals and plant species are currently facing extinction, with human activities and human-induced climate change key culprits.

A resulting wave of new regulatory protections and investor demands has shunted biodiversity risk from a local issue addressed with an Environmental Impact Assessment to the new frontier of corporate performance. Companies are now being asked to measure and mitigate activities damaging ecosystems, but will soon be required to dedicate time and resources to show how much corporate operations and strategies rely on elements like clean water or natural materials used for building – often defined as natural capital services. Afforestation and restoring wetlands as nature-based solutions to climate change will be discussed at COP26, adding a further regulatory threat to the viability of operations in high-value biodiversity areas.

However, conducting the kind of granular portfolio analysis investors and regulators are starting to require has long been hampered by a lack of quality data. But by marrying our Biodiversity and Protected Areas (Terrestrial) Index with asset level data provided by our sister company Wood Mackenzie allows us to analyse the level of risk at a country, commodity, and corporate level.

Key battery metal a major threat to biodiversity

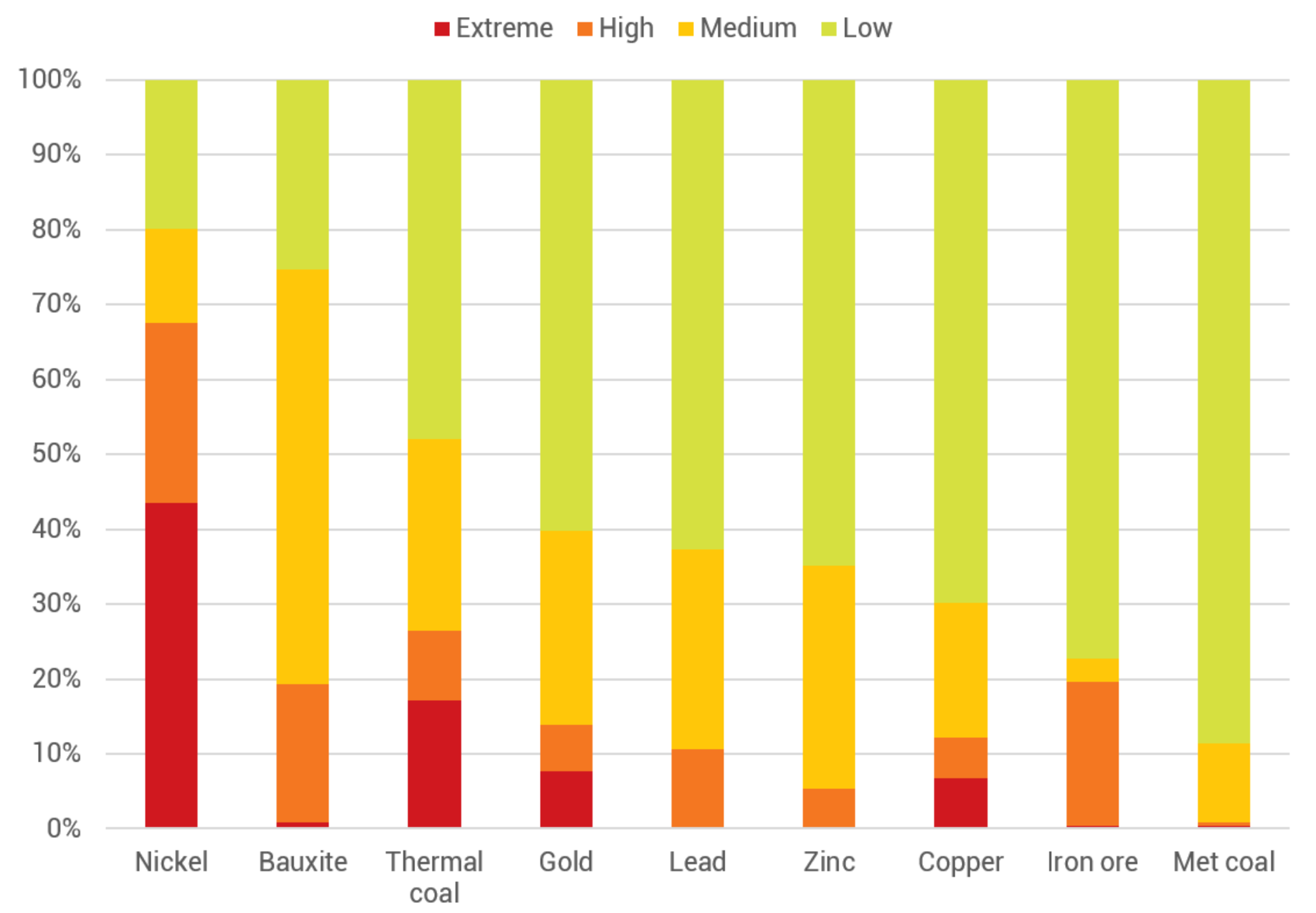

By assigning each mine a score from our sub-national index, we can aggregate how much production for each of the nine commodities analysed falls into each of our four risk categories. Nickel is the mined commodity most exposed to biodiversity risks according to our index, mainly because of huge nickel operations in biodiverse areas such as Indonesia, New Caledonia and the Philippines.

This raises a thorny issue for regulators and the industry: climate change is an existential threat to biodiversity as well as society, but can we justify destroying habitats to produce the materials we need to combat the climate crisis? As governments move to protect terrestrial biodiversity, perhaps deep-sea mining could be a solution. However, the Solwara 1 deep-sea mining project off the coast of Papua New Guinea shows there are a host of financial and ESG issues to overcome there too.

Looking at the other commodities, large-scale thermal coal production in Indonesian Borneo accounts for the bulk of its extreme risks score. Risks for copper are spread across multiple geographies including Indonesia’s Papua Province, Panama, Brazil, Botswana and Turkey. Iron ore’s biodiversity risk is primarily a result of mines in Brazil.

However, the mining industry and its investors will be pleased to see that for most of these commodities well over half of production is located in low risk areas for biodiversity.

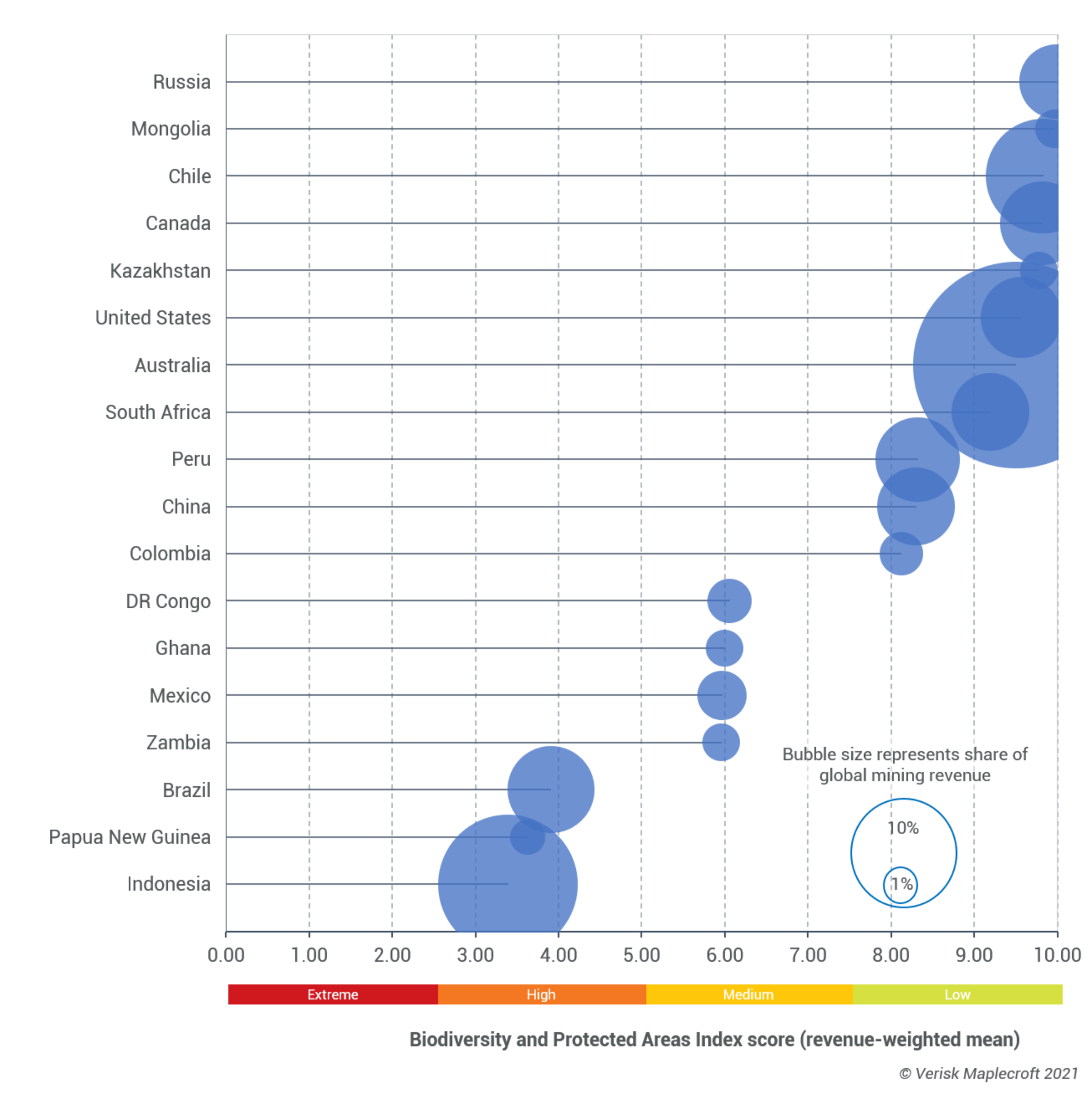

Biodiversity risks highest for operators in Indonesia and Brazil

Our data shows Indonesia as the highest risk of all major producers. The country is the world’s largest producer of nickel ore and home to one of the world’s biggest copper-gold mines. Meanwhile, Brazil - another high risk nation - is the world’s second largest producer of iron ore. Along with Papua New Guinea, these countries are all rich in globally-important biodiversity, but safeguards for those valuable species and ecosystems are under threat. Also, biodiversity risk varies considerably within these geographically diverse states: for example, gold mines in the north of Brazil are far higher risk than those in the south of the country.

Zambia, Mexico, DR Congo and Ghana fall in the middle. Each one of those nations boasts significant biodiversity that will need to be protected if mining operations in those countries continue to expand.

In the last grouping of countries sit well-established major producers, including Australia, Chile, the US, China and South Africa. Here, the risk is far lower due to mining taking place in areas with lower value biodiversity and greater protections for nature. However, as these markets develop, in part due to skyrocketing global demand for battery materials like nickel, we can expect biodiversity risk to increase in tandem.

Planting biodiversity on the corporate agenda

The difficulty for operators is that they cannot simply pick up mine sites and move them to areas without biodiversity risk. So, given the growing scrutiny linked to the expected demand spike for battery materials and other clean tech inputs, operators will need to get ahead of investor and regulatory demands.

A first step is to recognise that biodiversity risk is no longer a local matter, but part of a global trend that is making waves among a much wider audience. Operators need to work out a way of measuring biodiversity risk across their portfolios and calculate their exposure to the threats of natural capital depletion in a way that satisfies investors. By participating in the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures, known as the TNFDs, they can help shape what the global disclosure benchmark will look like.

Finally, operators need to factor the results of portfolio risk analysis into investment and strategic decisions, just as they have with climate-related risks. Doing so will help mitigate the investment and regulatory dangers of operating in high biodiversity areas and potentially even identify opportunities to enhance resilience, business models and social licence to operate.