North-west and central India is experiencing another extremely hot spring and early summer. April was the hottest since records began, with temperatures approaching 50°C. The world’s record May temperature was set in 2021, when Pakistan’s Sindh Province reached a scorching 54°C.

Around half a billion people are exposed to life-threatening conditions associated with extreme temperatures, with outdoor workers, the elderly and the very young most at risk. Indeed, India is rated as ‘extreme’ risk on our Heat Stress (Future Climate) Index.

These soaring temperatures are set to have a profound impact on the Indian economy. Heat stress will impact everything from productivity and energy demand through to coal supply and the pivot to renewable energy – worsening an already dire outlook for global energy and food prices.

Heat stress to threaten productivity, compound electricity shortages

The implications of heat stress are manifold. For one, exposure to prolonged high temperatures exacerbates health risks causing dehydration and fatigue, impeding workers’ efficiency. With such extreme heatwaves, business operations in India will likely suffer higher productivity losses.

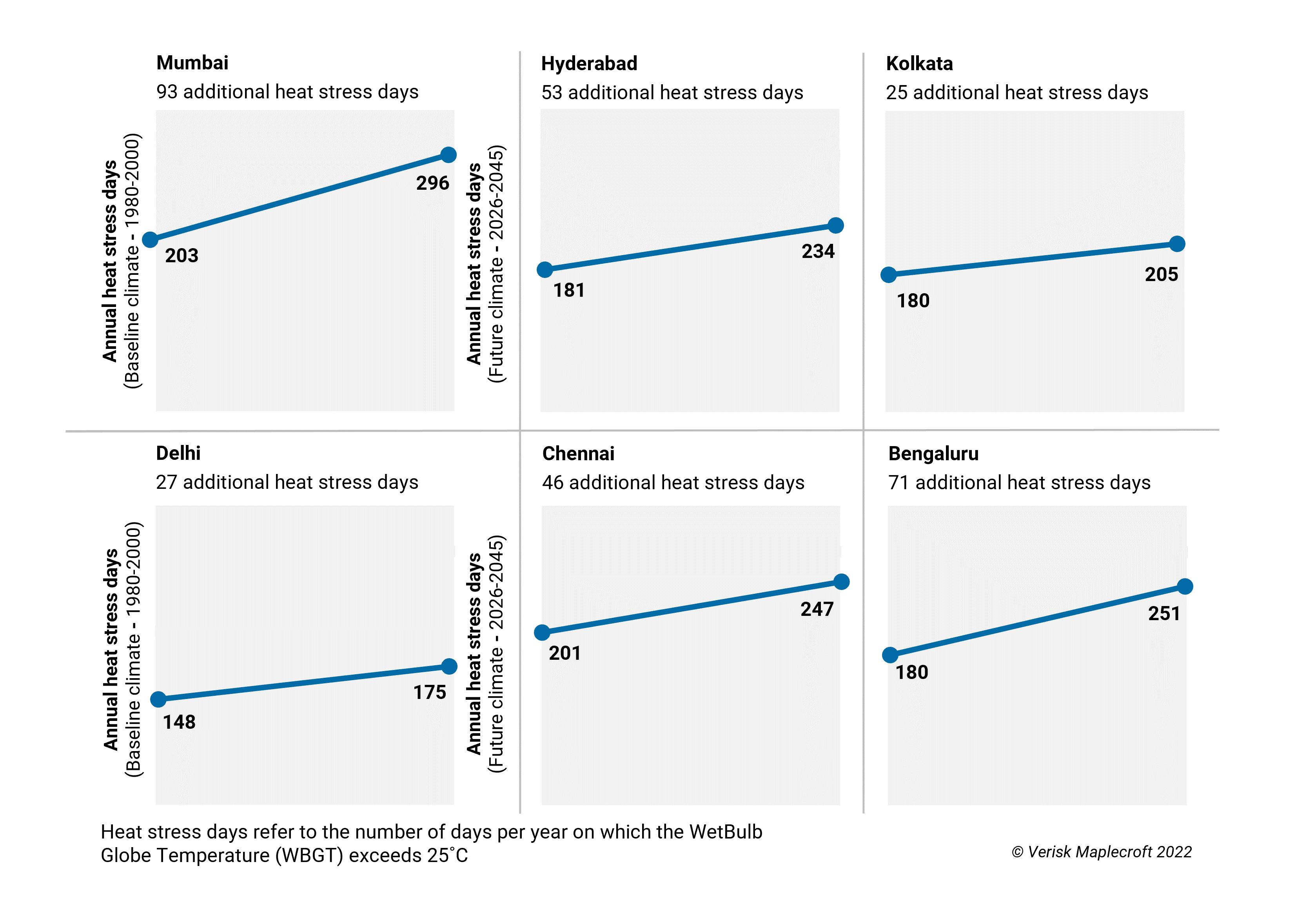

Agriculture, oil and gas, and mining are sectors where rising heat stress will impact labour capacity the most, as work is highly intense and often outdoors. The Indian economy is set to suffer in the long term, with heat-stress related losses putting 8.3% of export value in the agricultural and extractive sectors at risk by 2045.

Second, greater energy demand due to air conditioning and refrigeration will compound electricity shortages caused by shortages in coal stocks and soaring energy prices. Power outages are becoming more common, with Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and West Bengal most affected. Businesses, therefore, can expect higher operating costs, mainly towards alternative power sources such as generators to mitigate power outages.

At the same time, high temperatures will impact agricultural production, especially wheat harvest, with falling yields reported across north Indian states such as Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh. Lower yields will likely thwart India’s plan of exporting wheat to other parts of the world to fill the supply gap caused by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, exacerbating rising wheat prices and adding to the global inflation crisis.

This trend portends to the possibility of food unavailability in many countries globally, raising the likelihood of food-related civil unrest and political instability. The state-backed agricultural insurance scheme launched in 2016 has seen falls in acreage and uptake has been beset by teething problems.

Find out more about our Climate change & environment solutions

An uncertain outlook for coal

India’s coal imports are becoming increasingly uneconomical. This is largely a result of the disruption in coal supply due to the war in Ukraine, combined with weather disruptions in the mining areas of Australia, and Indonesia’s export ban on coal to meet domestic demand.

Amid expensive thermal coal imports, power and industrial sectors are now relying on domestic coal, with priority given to the power segment, creating shortages on the industrial end.

The same factors are raising the risk of a production snag in other energy-intensive sectors, such as steel and cement (both grid-dependent and with captive power plants).

However, coal demand is expected to stabilise by the end of Q2 as large steel mills will be under pressure to build up met coal inventories before the onset of the monsoon in Q3. Moreover, the newly signed free trade agreement between India and Australia will bring down the import cost of met coal, making it more attractive to steelmakers.

Supply chains to feel rising temperatures

As average global temperatures continue to rise due to the effects of climate change, extreme events such as heatwaves will become more common. As India’s hottest period of the year falls in the months of May and June, just before the monsoon season begins, we can expect more records to be broken over the next two months.

Temperatures of 54°C might be inconceivable to most, but with half a billion people in the world’s 5th largest economy at risk it won’t be long before global supply chains begin to feel the heat.